Drumlin Fever

by Graham Cotter

Poltergeist

Illustration by Audrey Caryi

The three boys were at the edge of the bluff looking down at the scene of their coming manoeuvre. Just where the road allowance plunged over the hill there was a slight knoll to one side of it, and on this there stood a solitary pine, fairly old, with irregular branches stretching out towards the east and south, typical of the windswept pines of Georgian Bay which were the stamp of Tom Thomson’s brief art. The boys had taken up their place, each on a separate branch. Brian as the youngest and lightest was highest; but also because he represented intelligence in this little army. Once his thick glasses were firmly in place, and his attention removed from the small insects and plants which were his companions when solitary, his eye could range across the countryside and provide his companions with both information and wide suggestions for strategy.

Bart, for all his energy and bossiness, was not the commander, but the scout. The wild gestures, squeaks and roars with which he entertained his friends and drove his mother to distraction, were silenced when serious warfare was at hand, and he could silently make his way to within even inches of the objective without being noticed. The boys were open in their admiration for his “Indianing,” as this tracking was called, and with his pigtail and almost Oriental cast of face, you might have wondered if he wasn’t a changeling sneaked into the Cart household from Alnwick Indian Reserve rather than the son of Professor Cart, whose father had come from an unpronounceable overseas kingdom.

Kevin was always the commander-in-chief. Although the same age as Bart, he had a qualities of leadership deferred to in the adult world as well as that of children. He was proud and vengeful, believed that he had a special mission which no one else had, and wrapped his sense of his own destiny in a vision and sense of mystery which was absolutely compelling to his friends. It was Kevin who would direct this operation, let no one forget it. He would never quite admit to himself that without his friends of course, there would be no operation at all.

“Now, men,” said Kevin, “the objective is that bare patch of field where the earth mover is and the little construction hut; there are several men down there and we are to surround that field before we attack.”

“Daddy said there was to be no attack,” said Brian. “We’ll attack them, and chew them up and our guns will rat-tat-tatt, rat-tat-tat,” said Bart, “We’ll give them an enfilade.”

“What’s that?” said Kevin suspiciously, looking down at where Bart bounced on his tree limb.

“Enfilade, enfilade! Military marmalade!”

Bart didn’t really know but loved the word, as he loved all words.

“It’s a kind of a trap, and you can fire at the enemy in that trap from all sides.” said Brian.

“Good!” said the commander. “Brian, from now one you’ll be known by code. Remember your code?”

“Yes sir, M.I.O.7.”

“Very good M.I.O.7, carry on. Now Bart, you’re Recce, for Reconnaissance.”

“I Recce I am, and Recce I’ll wreck ’em down there! Whee!”

Bart swung down from the branch as though swinging on a trapeze.

“Now M.I.O.7, how do you think we should plan our approach?”

“First,” Brian was slow and deliberate, “down the road allowance. We can’t be seen there. But then… if we cross the sand hills we can be seen from the road, and their trucks go along the road all the time.”

“Very good, M.I.O.7, what next?”

“We’ll have to go down by that little stream that runs in the spring, if we follow the river bed we can keep out of sight.”

“We’ll wiggle on our bellies, and come up all mudfish to scare ’em.” Bart was swinging upside down by his knees by this time impatient for action.

“But if we want to get close to them… we’ll have to run across the corner of the field while they aren’t looking, and get into those trees.”

“Dangerous, M.I.O.7. Your plan’s good up to there. But we’ll have to get on the spot and decide. Recce can scout for us when we wet there.”

“At your service, general.” Bart saluted upside down. “Now, men, down from the observation post. Recce, you go ahead, and M.I.O.7, keep your binoculars at the ready. Look out for ambush of the main force.”

Brian adjusted his `binoculars’ – which looked remarkably like his regular spectacles – as he came down the last tree. Bart was already moving slyly along the edge of the road allowance, from tree to fencepost, and Kevin was marching solemnly down the middle, whacking offending weeds and sumacs as he went by.

Apart from Kevin’s stick, which he thought of alternately as a sword and a field marshal’s baton, there was little sound as the boys passed. Brian could see the other two ahead of him, and his mind left the game for a while. Just as he loved groves of trees, so also he loved a road allowance. He had known this one all his life, and loved it the better. There was still a mystery about it for him. Soon, to the left, they were passing the rocky drop where the children’s play village was located. But that was almost too ordinary and civilized for Brian. He was more interested in further down, where a small gravel pit had been dug at the side of the road in to the bank.

There were trees at the top of the bank, now tilted at a crazy angle where the gravel had been dug from the side of the bank. An overhang of topsoil was kept in place by the roots of these trees, and wild grape vines cascaded down to make a curtain over the hole. It looked dark and mysterious, seen in broad sunlight. Brian had once ventured to the edge of the vine curtain by himself, and looked wonderingly at the stones and the lines of sedimentation and subsoil. They seemed to be special to that place, and to mark a secret entrance to a world he would like to see.

Brian’s fondness for closed-in places was also satisfied by the road allowance itself. These allowances are found all over Ontario, as continuations of existing roads, or mute signs of roads that once existed. Sometimes they are little more than a row of trees with a faint sign that once a secondary road was beside them to mark where the Crown surveyors meant the road to go. The Crown surveyors were obsessed with a grid of right angles and rectangles of land of various sizes: a mile one way, or three miles the other way. They paid no attention to the hills and valleys, but laid their lines out to put the stamp of square reasoning on the round or jagged contours of the land. That history was unknown to Brian, for whom the undeveloped roads or remnants of disused roads were signs of a mysterious past in which the land had been alive with straight lines and armies of earnest farmers who never moved on the diagonal.

Where men had once trespassed ineffectually, nature had, in Scace’s road allowance and many like it, taken over again. So now, instead of a blue asphalt or chloride surface, or instead of muddy tracks of the bumpy corduroy of the past, there was a carpet of wild flowers and weeds: grape, poison ivy, sumac, false Solomon’s seal, yarrow, and the green shoots of what later in the season would be dazzling goldenrod. Overhead, the trees on each side of the way met: beech and poplar and birch, the occasional oak and varieties of wild butternut. Like skeletal reminders of winter, dead elms were posted singly or in groups through all this greenery, and Brian could see a few younger elm, still alive, but showing clear signs that they too would soon be stark and bare, dead from Dutch elm disease.

Brian did not feel the anger his father did about the dead trees. Albert was angry because of the disease, and angry because no one, from the government to local farmer, would get rid of the ugly sights (Queen’s Park had a winter work’s programs to remove them from Highway 401, to get maximum public attention for minimum outlay of money). Brian liked the dead trees, just as he loved the bare hibernating live trees in the winter. Live trees in winter never let you forget they were alive, with their special sheen of life, rosy, or grey, or yellow, depending on the species; dead trees were hosts to all the little lives who were Brian’s special care – woodpeckers, beetles, sow bugs, mosses, and glorious fungi. A good fungus was subject for half an hour’s thinking for Brian, as it jutted out from a dead tree trunk like some cantilevered lookout post or Tibetan monastery. Brian was always angry when his brother broke off a fungus and then just left it without a host and hearth to cling to.

The rot inside a wooden log attracted Brian as he brought up the rear of the three boys. The log was a part of the tree which had fallen since he had last explored the roadway closely. As it fell, it broke and spilled out a rich red and brown dust from its inside. He stopped and rummaged in the log, and so disturbed a colony of sow bugs and several beetles. That is how it happened that he lost track of his brother at this crucial stage.

For Kevin, unlike Brian, was not daydreaming about bugs. He was getting angrier and angrier as he thought of his father’s anger at the Own Your Own Ontario people, and swiped more viciously at the plants as he went on. Then he stopped: a low whistle, Bart’s usual sign, had caught his attention. He whistled back, and went forward quietly. Bart whistled twice more before Kevin found him. Bart was flattened against a tree, and looked round with his finger to his lips. Kevin moved up beside him and looked along the line indicated by Bart’s finger.

The boys had not yet reached the culvert where they would normally have left the roadway and taken to the stream bed. They were actually at the slight rise in the path after its steep descent from Scace’s Hill, and to their left there was a rough untended field, with scrubby thorns and cedars growing sporadically. Across this field from north to south there was a slight bank, marked at the top by a decaying fence. Near the middle the bank was covered with a grove of evergreens. It was there Bart was pointing, at a group of men in a jeep.

Two of the party were surveyors, with transit and stick, measuring the obvious, as it always seemed to Kevin. The others kept going in and out of the grove, and consulting one another. The boys could not quite make out what they were about.

“Shall we sneak up on ’em and scare ’em?” said Bart.

“Don’t worry about scaring ’em, but let’s both go take a look.”

Kevin had forgotten that Bart was supposed to be the scout, and also that his Intelligence Officer should be consulted first.

“I didn’t know they were working this far over.”

“It’s not their land here. Still belongs to Letcherly.”

“No Bart, Letcherly’s land is on the other side of the roadway.”

“Think Letcherly owns coupla fields on this side too.”

“In that case, Letcherly never does nothing with his land. Probably sold it to Bumworthy.”

“How’ll we get over without being seen?”

“Grass is long enough. Down like snakes.”

“Snake brigade report for duty.”

“Carry on, snake brigade, Hssss!”

Over in the field, the foreman was scratching his head. He’d been sent out from the main digging to look for likely sources of water in the nearby fields. The fields did not belong to Own Your Own Ontario – they belonged to Letcherly, who wouldn’t even sell the Triple O options on the land. But Triple O was in trouble, and only the foreman, Carl O’Donnell and Bondsworthy knew it. The trouble was that there was no water at all where they were setting up their central lodge, and no water on any of the lots they had sold around the lodge area. Two witchers had been over with their witching rods and got nothing. The local well driller had gone down several hundred feet in several places with no results, except the fattening of his own pocket.

“I just don’t believe it, Mr. Bondsworthy.” Carl had said, “Every farm around here much higher up than this has water, and not so far down. Letcherly has all sorts of water right next, I’m sure. Stream runs there every spring and the hillsides are soggy till July.”

“Letcherley around much?” Bondworthy asked.

“Naw, he doesn’t bother.”

“Go over and look around. Try some dynamite.”

“Dynamite! you can’t hide that!”

“Risk it. In one or two of the soggy spots. If nothing happens, we don’t know anything about it; if water gushes, we’ll offer Letcherly enough to wake him up.”

“What’ll I say if we’re seen?”

“Take a survey crew and have them fuss around. You and the Toad look after the dynamite. I’ll take the responsibility.”

“Okay boss, if that’s the way you want it.” Carl moved away.

“And Carl!”

“What?”

“Don’t go any where near Scace’s.”

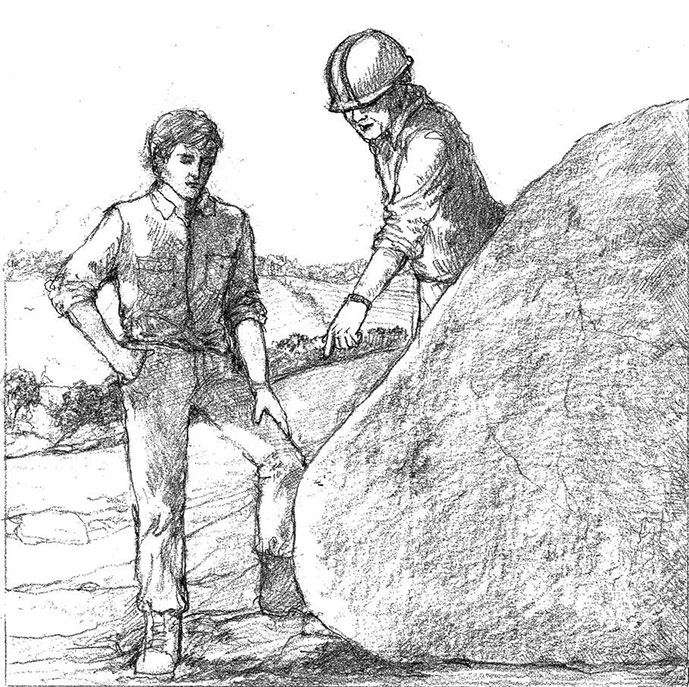

So Carl was now faced with one of the most stupid situations he’d ever been in. Getting water with dynamite in this kind of country was about as modern as Moses and the rock, and much less effective. But he had decided on a rock, in fact. Along the bank in the middle of this field there were a number of deadheads poking up from their ancient burial places, and the biggest was in the middle of the little grove of pines. It was a smooth glacial boulder, about four feet out of the earth and about eight feet across. At its feet, down the bank, the ground was soggy.

So he told the Toad to drill as far in under the rock as he could. Harold Todeski was entirely unlike his nickname. He was a more like an intelligent lizard, thin, quick, his skin drawn taut across the pointed bones of his face. Of mixed Norwegian and Polish blood, he had escaped from Poland as a teenaged boy, and learned explosives in Scotland with the Polish forces in the Second World War. He had moved to Canada in a burst of unhappiness when Poland went Communist after 1945, and lived near Rice Lake working with dynamite for whichever construction company needed him. He manipulated an earth augur, and shook his head at the crazy idea. Most likely O’Donnell and Bondsworthy would get a big hole in the ground and splintered rock and wood for a hundred yards around. He didn’t care, he just had a job to do.

The charge was set, and as Harald was connecting the leads it happened. The survey crew were going through the motions for appearances’ sake when in rapid succession each was struck by a small pebble, on the hand, the other on the cheek.

“Damn you Bill” yelled the man with the transit.

“Damn you Joe!” yelled the other.

Before they had a chance to see that each had been hit, each was hit again, with slightly larger stones, and low on the body. there was no one in sight. “Hey Carl!” shouted Joe, “Someone is flinging stones at us.”

“Quit fooling you guys, don’t make so much noise. We’re not supposed to be here at all.”

At this point a small sharp wood knot hit Carl in the forehead and he began to bleed. He ran around the clump of trees. There was no one in sight. Shouts from the surveyors showed they were still targets.

“Okay, Carl, ready now,” said Harald, coming out with the wires in his hand.

“Never mind that, Toad, get in the jeep, you guys get in the jeep; that old queer Letcherly’s around here somewhere throwing stones at us. Let’s get outa here.”

“Can’t leave that stuff in the ground …”

“Todeski, I said git. You’ll get your pay. We’re clearing out before we’re all in court for trespassing.“

The jeep started up, the surveyors still looking suspiciously at each other, and Carl trying to stop blood running down in to his eye. As the four wheel drive groaned over a low stone fence and into the distance, two dusty figures rose, about fifty feet apart, and Bart and Kevin danced, Kevin trying to keep up with Bart in cartwheels, springs and leaps, all in silence; their merriment showed only in action, not in sound.

Drumlin Fever is now Available for Sale

Great News! Drumlin Fever has now been published. (Sept 2020)

The cost is $20 + $8 shipping and handling if delivered within Canada.