Drumlin Fever

by Graham Cotter

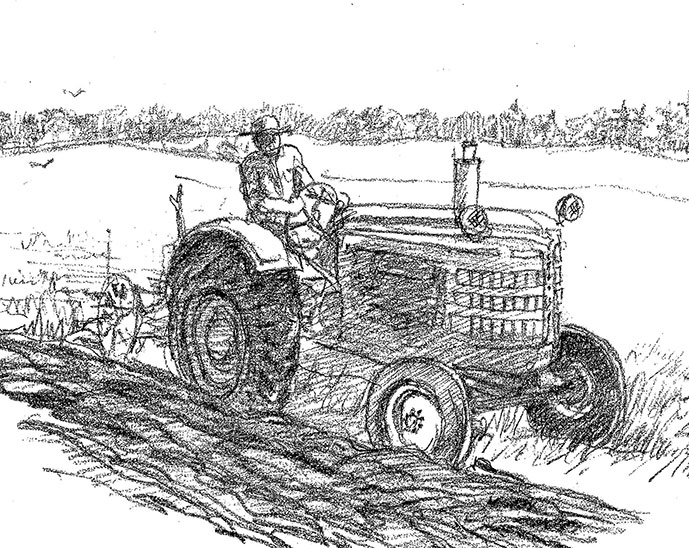

Tractor by Searchlight

Illustration by Audrey Caryi

The whole project of using dynamite to find water had been very doubtful from the beginning. Most of the drumlin hills had springs and soft spots at the side which water might come in smaller or larger quantities, but drilling was by far the more usual method, and explosives were more appropriate for a rocky landscape. But the Triple O management had been panicky, and the foreman believed that Todeski could do miracles with explosives. Todeski himself had been in the “hyped” frame of mind which went with explosives, and this had led to a mistake which he was not to realize until it was too late.

Normally, dynamite would be exploded by a detonator through a little machine which created enough electricity current through connecting wires to explode a cap, and the shock of this would set off the dynamite. Todeski’s specialty, however, left over from the wartime days, was a slow burning fuse which would eventually explode the cap directly, and he had already attached such a fuse to the dynamite charge he had buried under the big rock when the hullabaloo with the pebbles had driven the crew away. Todeski had done this automatically, and then set out to lay electric wires to a detonator, intending to remove the slow fuse later. He was a dreamy kind of man for whom explosives were a beauty, and moreover, he enjoyed the risks much as a little boy, having lived dangerously too long in the European war to be content with dullness of life as he found it in the Ontario countryside.

Thus it was that under the rock beside which – on the other side – the two girls were in a trance-like sleep, there was not only a large charge of dynamite (enough to demolish a two storey building) but there was also a live fuse, slowly burning to its inevitable end.

*******************

George Wiseman was readying his tractor and plough for an evening’s work. His homestead was further along the same escarpment as Scace’s Hill, to the west, and above Cartagena, and he had several acres of rough land to prepare for seeding. Evening and night work were his specialty, because he did part time work for salary every morning, and then sold his services for various farming jobs during the day, so that he could attend to his own acres at night. Besides, the quiet of the evening and nightfall gave him an opportunity to think and to put together conclusions about the various people he had met in conversations he had had during the day.

This evening his thoughts were divided between the missing girls and his chat with Professor Cart about water. He had talked over the disappearance of Linda and Debbie with his wife over a brief supper.

“Thelma Scace gives those children too much freedom to wander around anyway,” said Mary Wiseman. “Something like this was bound to happen.”

“I don’t know. Kids have generally been pretty safe around here, since I was a boy, except for falling into rivers. It’s a long time since we’ve had to worry about wolves and bears. Leastwise, I think that, though some figure Andy Small was taken by a wild animal. I never held that. I held that Andy cleared out to live with his cousin in Tronna, and nobody said nothing about it, since Miz Small couldn’t cope with the children she had left, nor with her no-good husband.”

“George, it couldn’t be anything like that. But you know very well we still hear wolves around in winter, and we see bear tracks.”

“Wolves don’t attack people unless they’re rabid or starving. They’d keep well clear of girls that size; besides it’s not winter.”

“I’d be afraid of some pervert picking them up. That fat man in green from Triple O looks like the kind of man who’d enjoy pulling down little girls’ pants.”

“Mary, you shouldn’t say that sort of thing! It’s libelous, for one thing.”

“George, has that man been after you about selling?”

“No, not since the letter they sent to everyone. From what I hear, Albert and Thelma Scace gave him a run for his money, just yesterday. Albert has a bad enough temper, but with Thelma and her sharp tongue, and all those brains, I’d clear out in a hurry.”

“Just yesterday? George, you don’t think Bondworthy would do something deliberate to those children…?”

“No Mary, they wouldn’t do that. You’ve been watching too much TV from Rochester. Modern city crooks aren’t like the Tracys: they hurt from a distance so’s not to be blamed or labeled.”

They ate on in silence for a moment, then George said, “I think it’s a natural accident of some kind. What’s really strange is that it should happen to two girls as old as that, and no news.”

“Well it’s only since noon really. If they don’t turn up overnight it’ll be a much greater worry.”

“I must be off now. Get word to me if they want me to join in the search.”

George had then set out and was soon going back and forth across the field. Surface water he could understand: he had only to look at the field to see the darker patches where the moisture was to be found, and these same patches would be greener when the crop grew. What he didn’t understand was the reservoirs of water underneath, and how they could be high in some places and low in others. He was still puzzling over this when he thought he saw an animal scrabbling in the bushes at the far edge. As the tractor drew near, the animal didn’t run, and then he realized it was a boy. It was Kevin.

After his quarrel with his father and his own self-accusations Kevin had crossed several fields and a small wood without being sure where he was going, and was sitting disconsolately on a stone when George came to him. He was a sad sight, the tear marks streaking down his face, and his hands dirty and cut where he had carelessly rushed through thorn and stumbled on gravel.

“Well. it’s young Kevin. Have your sisters been found yet?”

“No, Mr. Wiseman, I don’t think so.”

The misery was evident in his voice.

“I thought maybe you’d be out looking for them?”

“I was earlier.”

“You don’t think they came this way, do you?”

“No.”

“Would you like to get up beside me on the tractor?”

“Oh, gee, thanks, yes, Mr. Wiseman.”

He climbed up and the tractor moved off.

George was quiet for a while.

“Guess your folks would be pretty upset till Linda and Debbie come home.”

“Yes.”

“Ever go off like this before, those girls?”

“No.”

More silence.

“Don’t suppose they ran away?”

“Might have,” said Kevin very quietly. “Ever feel like running away yourself?”

“Yes. Used to run away regular, myself, when I was about your age. My Dad was very strict, and I thought I’d teach him, make him think I was dead. Trouble was he’d wallop me worse when I got home. But it was good, feeling free and all on your own and even good feeling scared.”

“Did you think that, Mr. Wiseman?”

“Yep.”

“Maybe.. maybe the girls wanted to feel free like that too.”

“Why, I don’t suppose anybody’s strict with them in your house?”

Kevin was silent. George looked at him:

“Or mean to them?”

Kevin nodded, a tear starting down his face.

“I see, well I guess you didn’t really mean to be.”

“Trouble is I did mean to be. I hated them”

The tears were coming faster now.

“Say now, I can leave this field till later. Why don’t we drive down somewhere nobody’s looked before. We have a better chance finding them while there’s daylight.”

“Yes, lets. If you can take the time!”

“Never too little time to do a neighbour a good turn.”

He turned the tractor at the end of the field, and they went into the farm lane which led over the escarpment to the field below.

*******************

It seemed to Debbie that she had been lying a long time, with Linda cuddling her, looking at the great mountain, and wondering at the strange things happening in the sky. For the sky was lighting up with brilliant sunshine and then darkening to night: sometimes inky, sometimes star clad, sometimes moonshine, in rapid succession. There was something wrong with the sequence too: the sun seemed to be rising in the west, the dawn looked like sunsets, and setting in the east behind that great mountain. Clouds did not move across the sky in any leisurely way, but so fast they streaked and the girls’ minds were dazzled and numbed by the rapidity of change. And there was a gradual cooling in the air: they were warm themselves, but the air was cooler, and more clouds were in the sky in both night and day.

It was like lying in bed with the lights of cars coming across the hill, shining for a moment in the window, and then they disappeared in the distance, and then she drifted off to sleep. Debbie had a special experience as she drifted off to sleep in her own bed, on any night. She would see strange shapes in front of her closed eyes, like soft dark red worms that swam in some liquid and then suddenly the page would turn, all the worms and the shapes turning with it. Another page would be there, but before another page could turn there would be a shaking of everything in her sight, and she would lose consciousness in a delicious sense of herself swimming among delightful feelings and tastes, her skin soothed, all appetites met.

So it was in this strange experience of the reversing day and night, and the friendly menace of the great rock mountain. She was not frightened. She was waiting for the page to turn, and for the shaking to begin.

*********************

In the hill above Debbie and Linda, and in the ground beneath them, the earth waited silently as it had since the turmoil of the glacier shaped it. Far, far down, beyond even the influence of the glaciers, the hundred mile thick mantle which sheltered the internal stresses and smoldering high temperatures of the earth was like a great iron foundation: radiation of heat could pass up from it, but no tremors of upper movement could pass down through it. Above this, the earth’s crust of hardened rock, made in fires of long ago took various shapes: here within fifty miles of the rocky surfaces known as the Laurentian Shield, that same shield lay far underneath the glacial deposits above.

The glacial deposits were pulverized rock, the pebbles, sand and boulders produced by years of abrasion between the glacier and the fire-made rocks of the shield. These in turn had hardened under pressure into water-made rocks, sandstones, shale, limestone. Then the final withdrawal of the glacier to the north-east had carved out the river channels and the escarpments of great rivers like the Trent; in the smaller scale the drumlins and the moraines which were Professor Cart’s great interest (after compost).

In all of these were the ground granite, hardened sandstone, re-ground stone mixed, and clays found in layers, clays through which water could not penetrate as they could the looser matter, which looked as though it had been tilled – as it had, not by man and plough, but by the glacier.

And so it was that the great water reservoirs were under the ground as the Professor had said. What he did not know was that there was a very large such reservoir under Scace’s Hill. Normally it leaked into the stream, the Salt River, the Burnley River, the pool by the toy village, the quicksand in the cattle pasture; as rain and snow waters penetrated the upper ground, the inner sogginess of the drumlin escarpment could hold no more, and out came the surplus. Some was still coming out. But not at the foot of the hill in the lowland occupied by Triple O. Some inhibiting factor, unknown, was stopping the usual exits. The boulder by which the girls and the dynamite both slept went deep into the ground, hundreds of feet, a great cliff of rock snatched from the shield in a raging storm in the glacial age, and about the roots of the rock the gathering water pressed.

What held the waters back? At the time no one even knew they were held back, just that the lowland had dried up. Later after the disaster, geologists drilled and surveyors mapped, even witchers came around, but no one ever found out. When the farmer stopped farming and the bulldozers began bulldozing, a change came: from such descriptive facts myths arise, and the superstitions are invented for want of explanations which satisfy the mind.

*******************

George and Kevin were exploring a lowland which had not dried up, the lowland marsh around the Salt River, separated from the Triple O property by the sand hills and the road concession. George had driven his tractor around the edge of the marsh, and then the two dismounted and walked cautiously among the willows and rushes into clumps of marsh marigold, now just past blooming. They called the girls’ names as they walked, and searched for signs of footprints or disturbance.

The edge of the marsh like the field next to it: tussocks of tall grass and scrubby thorn trees, a few cedars and some hardwood. Then they found they were having to look carefully where they put their feet, walking on the tussocks if possible, and watching out for roots of trees. Indeed, as they went further, the trees grew larger and part of the marsh was really a forest, intersected with streams and branches of streams and new springs in unexpected places. The size of the trees made it hard for them to get their bodies through even when they could find adequate footing. There was no sign of human disturbance and the birds were preparing to go to bed. The night frogs and crickets had not yet begun their chorus.

There was a sudden rustling behind some bushes.

“Linda! ” called George, “You there?”

“Debbie!” added Kevin.

In answer an owl hooted and whooshed by them, passing just a foot above the farmer’s head. Kevin was paralyzed by fear, then his friend said:

“The girls can’t be very close if that fella’s flapping around much.”

And thought to himself “Unless they’re asleep or dead.”

The two pressed on past the bushes from which the owl had emerged. There was a bright light ahead of them, lighting up cedars and birches twenty feet above their heads. The sun burst through in a final dazzling brilliance, just before it disappeared behind the escarpment. Night would fall sooner down low that on the heights. They struggled a few paces, Kevin a bit ahead, then he whispered:

“Look!”

There was a kind of clearing, in the middle of which a piece of cloth was clearly waving from something. As they came closer they found there was an almost perfect circle among the trees: in the midst of this there was an odd assortment of debris. A partly rotted wagon wheel stuck out of the ground, and pieces of a motor car chassis, a cog wheel from some machine, and perched on a partly fallen tree; the half circle shape of the metal frame of an old tractor seat, wide enough to hold the fat man at the circus, and upended like some arch leading to a new discovery.

A rag was caught in the metal work, idly flapping. The circle, perhaps originally an attempt to damn the river which followed through the marsh, was no more than a damp patch, picturesque in the woods, obscene if multiplied by thousands and stretching across the land.

“No point going further, Kevin. By the time we get back to the tractor ther’ll be just time to get you home by dark. No point having the folks worried about you too. The girls aren’t hereabouts.”

*******************

Half a mile or more away, the girls were still asleep. Perhaps the same spell was on them that once was on the waters beneath them. They were not cold, in spite of the advancing dark. The night would be warm anywhere, and the trees above them – which did not appear in their dream – kept off the breezes. Even the mosquitoes kept their distance perhaps because of the odour which was arising from the rock. On the other side, the fuse burned on, subject to no spell or witchery, its slow progress marking “now” in a steady chain of cause and effect.

Drumlin Fever is now Available for Sale

Great News! Drumlin Fever has now been published. (Sept 2020)

The cost is $20 + $8 shipping and handling if delivered within Canada.