The Topher

by Graham Cotter

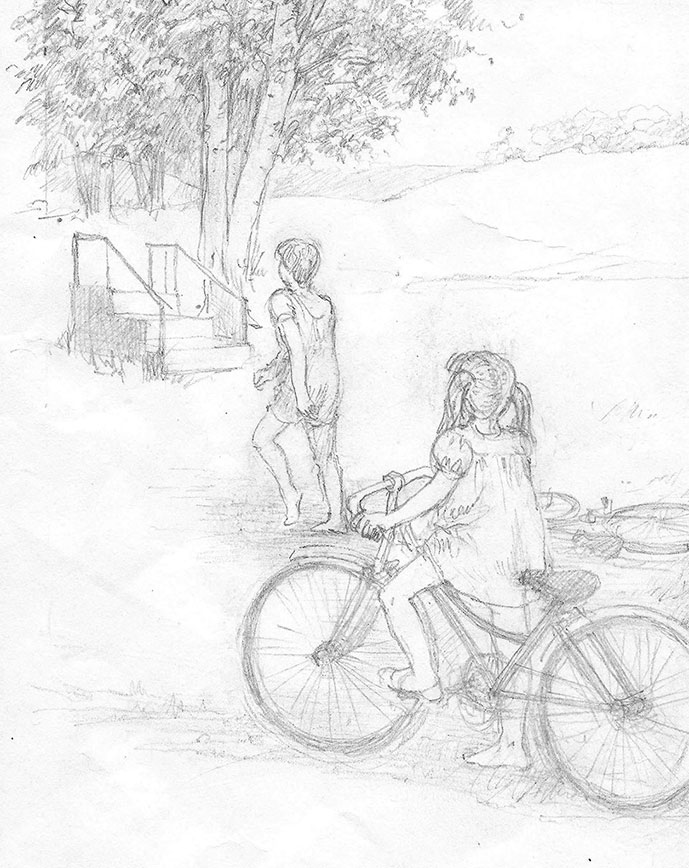

Steps to Nowhere

Illustration by Audrey Caryi

The two girls had just reached the top of the hill, walking their bikes. Behind them was a long hill they had coasted down, but the rise they had just walked had been too steep to maintain their momentum, even with hard pedaling. They were seven and nine years old and strong, but not Olympic, cyclists. And it was a hot day in August. To their right had been a farm house with a red painted porch which seemed to lean out over an untidy yard. To their left a wholly abandoned house, grey with age, topped the hill. And now before them was another easy slope. Mounting their machines, they were off down it, the older red-haired girl in the lead, her blonde sister just behind her.

The road leveled off and came to a crossing. To their left there was a cozy old farm house, with lilac bushes and a little garden gate, as well as all the barns and equipment of the farm yard behind. To their right, a new house had been built, low and modern, faced with an attractive rosy brick, its grounds as yet unattractive and bearing the marks of construction.

The crossroad itself was odd. To the left a trail bore up the hill – scarcely an inspiring road to a motorist, or even a cyclist, but interesting to a hiker, disappearing among hardwood trees in the distance. The road directly ahead was gravel and moved off into a forest conservation area, with rows of new trees trying to catch up with the distant plantation of 1924. The latter, in turn, looked rather new compared with a few hard old pines which had been small when the pioneers did their survey.

The road the girls were taking was paved, and swung around to the right, sharply. But before they made the turn they stopped, gazing at the clump of birch trees to their left.

“Look!” Said Debbie, the younger, “Look at the steps!”

“Those are Steps to Nowhere, don’t you remember?”

“Yes, they don’t go anywhere!”

Sure enough, there were concrete steps, with pipe railings at each side, rising about three feet in the air, going westerly, but leading only into a clump of birches.

“Remember Norah?” said Linda. “Norah?” wondered Debbie.

“Norah with the long black hair who looked after us one summer?”

“Oh yeah, I do.”

“Silly Norah, she was fooling us.”

“Maybe she was. But she wouldn’t go up the steps, and she wouldn’t let us go near them.”

“I’d go up them. I’ll go up them right now.” Debbie laid her bike at the edge of the gravel road and walked towards the steps.

“Debbie, no!” shouted Linda, “Look out!”

Debbie stopped, and looked back “What is it?”

“Poison ivy, all around there. Keep away!”

There was poison ivy, and Debbie’s legs were bare.

“Okay,” she said, “but I’ll do it some other time. Just you wait. I’m not scared. I’ll go to Nowhere and see what it’s like.”

The two girls rode along on the country road, now going north. Over a slight rise, they came to a corner where the pavement veered right again, and a trail led up a hill in front of them. To their left was the ruin of a barn or a house, and a freshly bulldozed cattle pond.

“Isn’t this Foxes Corner?” called Debbie.

“Yep, and now we’re coming into Bird Wood.” The family had seen foxes there, one of the few places you saw foxes hereabouts, and so it had been named.

Now they rode on, with hardwood branches meeting overhead. The woods were lush with summer growth, and deep beds of leaf mold covered the ground. The girls stopped about halfway, and listened. They could hear birds chirping and twittering in the trees, and beyond those noises, just silence. They knew that their father, returning from his office in Cobourg every evening, would stop the car here, and turn off the motor, and listen. It was a family ritual, almost an act of worship. The silence was as beautiful as the counterpoint noises of the birds.

By common consent, no one spoke in Bird Wood, no one in the Scace family anyway. It was as though the owners’ “No Trespassing” signs spelled “Silence”, or as though to speak would be in fact to trespass, to send out unwelcome footsteps of sound across the untouched forest floor, and break some spell which could bring disaster. So, after a few moments, the girls rode on, the slight grind of their tires on the surface breaking the hush. When they came opposite a huge pine, they said together “Tall Tree” and giggled. After Tall Tree there was a meadow on their left, blue with Viper’s Bugloss, the plague of cattle farmers and the joy of oil painters, and on their right the hardwood forest gave way to cedars and marsh, bordered at the road by a stump fence, the snaky roots of old torn-up trees forming an effective edge between the roadway and the wilderness beyond.

Suddenly, they were over a bump, and the river and bridge were before them. It was a stream, hardly a river, and it began three miles away where the county road crossed Highway 45. Further downstream it passed through Warkworth and was called a river, just as the “hamlet” of Warkworth was dignified by being called a “village”. But it was not the stream that caught the girls’ eyes: where the stream, still almost level with the lawn even in late summer, curved past the bridge out of sight, rose two strange shapes, flat-sided, sharp-edged, acute angled, red on one plane, white on the next, like mushrooms growing on some geometrical planet, where living forms took crystal shape.

They stopped on the bridge, and gaped at them. Then they began to look further on the closely clipped lawn. It rose up a gentle slope to a low house, almost barn-like but with a gambrel roof. The house was old, had once been a cheese factory, but was now lived in and was neatly painted white. But it was not the house that caught their attention; they had seen it before. What astonished them was that more of the same shapes were all over — some lying nearly flat, with crushed angles, others reaching in various directions, yellow and blue. There were no trees, shrubs or flowers, only lawn and the Shapes.

“What do you s’pose they are?” said Linda.

“Pity we don’t have Norah”, said Debbie. “She could tell us. Maybe they belong in Nowhere!”

They stood with their bikes in an unnatural silence, afraid. They had actually reached Burnley, a place just big enough — six houses and a community hall — to have a name, so they were not far from help if help was needed. But it was their minds that were overcome, no physical instinct of danger pricked their scalps.

Then the silence was broken by a cracking noise, and a faint voice, “Linda, Debbie! Where are you?”

Back home at the Scace farmhouse near Warkworth, Thelma Scace, the girls’ mother, had been weeding and hoeing in the vegetable garden. A large blonde woman with a handsome face, her strength of character was matched with strength of body. A good deal of her body was showing, in fact, for she was in halter and shorts, looking more like a city woman than a farmer’s wife. She liked to get a good tan, but her face had had almost too much this summer, and she was wearing a big floppy hat.

There was great contentment in working your own garden and watching your own vegetables come up to help keep down the cost of bringing up a family of four, not to mention two good adult appetites. She had a restless and critical mind, but for once, she was also content with her family. Her husband, Albert, worked all over the county for the Conservation Authority, but had his office in Cobourg, and he was finding his work very satisfying at last: various levels of government were really beginning to care about the preservation of the land, of the landscape and of both farm and recreational land. This meant that there was now enough public awareness of the issues to keep the governments interested in more that token conservation. So Albert was also having a good year.

Other years, he had spent evenings working on the land, keeping up some pretense of working the Century Farm he had inherited. But this year he had employed various neighbors to do most of the work, and even given up, for the moment, trying to break in his two boys to a sample of farm work: Kevin and Brian were sent off to summer camp.

This was a relief to Thelma, who was very emotional about her eldest, and worried about the younger boy’s asthma and related problems. Now they were in good hands, and the nagging battles between the two boys and the two girls could be forgotten for a month.

There had been a nasty incident that June, connected somehow, Thelma was not sure how, with a feud between Kevin and the girls. And the girls had been missing, feared dead, for a whole day! They had been found, unharmed, and Kevin had found them, at some cost to himself. There had been a closer family feeling for weeks afterwards, but such things wear off with the very young and the boys being away for a while made life easier all round.

The conflict was especially painful for Thelma, because she saw in it some reflection of her own strong feelings. She firmly believed that what boys and men could do, girls and women could do also. Her husband agreed, but she was frustrated by their easy acceptance of traditional roles. Her talents for business and for writing, by which she had made a living before her marriage, were largely unused. But she was determined that since she had to focus on child-raising and not breadwinning, she was going to make a good job of it. When she saw at least one boy growing up to be very masculine, and at least one girl equally exceedingly feminine, she was bothered – she was frustrated by their easy acceptance of traditional roles.

The girls’ disappearance in June had led to a further problem: should their freedom to wander be unrestricted? Thelma was against such restrictions in principle, yet instinctively she knew that she must keep track of them to avoid a repetition of the near tragedy in June. Brian, the family thinker, had come up with a solution: Walkie-Talkie! So Thelma could switch on and check up on the girls any time. It cost a lot in batteries, but was worth it.

It was about time she checked on them and their bicycle tour. So it was their mother’s voice the two girls heard as they stared at the strange Shapes in Burnley. Linda reached over to Debbie’s bike, and touched a button on the walkie-talkie strapped to the handle bar.

“At Burnley, Mum!” she called, leaning down to the mouthpiece.

“You’d better start back girls, you’re nearly out of range.”

“Okay, Mummy,” said Debbie.

“Which way are you coming, then?”

“Along the road towards Bantytown, Mum.”

“Okay, take it easy. Nancy and Out!”

“Nancy and Out,” shouted the girls, greatly cheered.

They didn’t see why a boy’s name had to be used between women, and since their parents had great friends named Roger and Nancy, they chose “Nancy” to replace “Roger.”