Drumlin Fever

by Graham Cotter

The Alarm

Illustration by Audrey Caryi

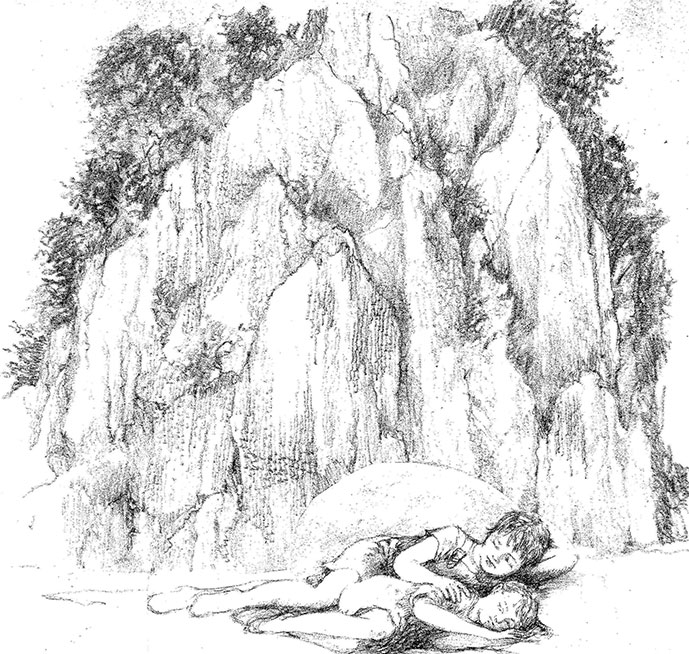

Debbie’s head lay on her forearm as her eyes slowly opened. She saw the needles and the wild flowers. There appeared to be a great field, and here and there beasts hurrying about their business. The needles became strange living sticks as big as trees, the wild leeks and other plants, monsters of the encroaching forest. Her eyes wandered over these, looking for living creatures. One emerged, walking up the side of a plant: a true monster, reminding Debbie of the huge trucks which carried other trucks on their backs on the highways, or perhaps the forester’s machine with an elevated arm in which a little man sat to cut trees. But this monster’s head, with two huge eyes, and short forelegs which rubbed together, stretching its great sharp claws. It stood absolutely still, half way up the monster tree. She shuddered and looked away.

It was then that she saw the mountain. It rose from the plain with its stick trees and its monster trees like a sheer wall of rock. Its surface was smooth except for half-way up, where it was deeply scarred as though some great machine had ploughed lines, parallel but curving down its face. That was it! Those lines made the only face it had, no clear definition of nose and eyes, but lines that gave the whole blank mountain an expression of puzzled concentration, like furrows in the brow of an otherwise faceless head.

The texture of the mountain itself was beautiful. Debbie could see great shining crystals, dark like garnet, light like topaz, some clear as diamond, making up the whole surface of its face. On one side there seemed to grow a kind of green vegetation, fine shrubs pressed together making a mat all along the left side and out of sight as she looked. And in the crystals of the rock she could see reflected a blue sky and clouds. She turned on her back.

“Oh, Lindy, look!”

The two girls were looking now at a sky such as they had never seen before. It was like the inside of a great dome of glass, and iridescent ripples of colour radiated out from where the sun seemed to be. They could not see the sun — just as well! — but knew it was there, behind the fantastic crystal. Clouds crossed their sky, like wispy fog or mist, and seemed to have no dark side: only a bright edge towards the focus of the sun, and a coloured edge the other side.

“Wonderful!” said Debbie.

Then a strange thing began to happen: the sun’s focus began moving slowly down behind the mountain, and the rays of the colour on their sky’s dome became more brilliant and deeper; at the same time, behind them, they were first aware, and then they saw, a line of darkness move across the sky, blurred at the edges, but

inky black behind. Soon the darkness filled half the sky and moved quickly to blot out the light. Then as the final rays of light disappeared in a red glow behind the mountain, their sky filled with bright spots of stars, twinkling and moving, and in places like a dust of tiny lights stretched across their vision.

********************

About four o’clock, Thelma went out and called the boys. Her own two were playing near the barn but Bartholomew had gone home. There had been a great wash-up after the morning’s adventures, and the boys had poured out their story to her over lunch. This was another of the days her husband was not working in the neighborhood, so he was not there to share in the news, and to exclaim, as she did, over the horrors of the Triple O.

“I wonder” she has said at lunch, “when it will all end. Or if it will end before they tear up the countryside and make it look like Oak Ridges.”

Oak Ridges ‘village’ was a rural slum, taking its name from the sand-hill studded moraine which stretched across Ontario from Orangeville to Trenton. Thelma had lived there briefly as a child while her Ukrainian born parents were making their escape from living in Toronto.

“Gee, if only the Tracys were still around!” Brian had put in. He was still feeling bloodthirsty after his narrow escape.

“You mean, get them to shoot up Triple O!”

The thought had tickled Kevin.

“Or run them down with tractors, and set their houses on fire!”

“I wouldn’t wish the Tracys even on the Triple O” said Thelma. “I can see their usual performance of setting barns on fire and stealing cattle and equipment might harass the Triple O: schemers and cheats, ready to get around the simple, the widow and the fatherless and do them out of their inheritance. Triple O is doing that, not only robbing the inheritance of rural Ontario, but probably cheating the people with its small plots of land to right and left. Their rate of interest alone is a sin.”

“Tracy’s only kill each other, eh, Mum?”

“They killed off one brother, and someone not in the family went to prison for it.”

The conversation had dwindled, as Kevin went into a daydream about setting a mob of screaming Tracys to cheat and pillage the Triple O. Thelma had thought soberly about the disruption of country life which the Triple O invasion was likely to bring, and the dirty politics people were preparing to play in order to buy bigger cars, and to tear down old rumbling houses and replace them with the latest long, low boxes they had seen on the TV from Buffalo or Rochester.

But now it was mid-afternoon. Thelma had fallen asleep, and just wakened up to realize that her girls had not returned. The boys came running to her call.

“Kevin, have you seen the girls?”

“No Mum!”

“They were taking a picnic to the toy village. See if you can find them.”

She reflected on Kevin’s bad relations with the girls –

“And take Brian with you if he feels alright.”

“I’m Okay, Mum. I’ll go too.”

********************

It was an hour later when the boys returned. There was no sign of the girls at the toy village, but there had been a spot in the grass adjoining the field where there were traces of their having eaten. Kevin and Brian had returned to the road allowance and gone down to the sand hills and even crossed the road to Morganston and looked in the creek on the back road to Norham. It had not occurred to them to go back to their respective scenes of battle, since they thought the girls would have been having their lunch about the same time as their brothers’ adventures.

“They musta gone to Warkworth, Mum.”

“But they never go without letting me know!”

Thelma was worried. Added to the general feeling of insecurity, with talk of the Triple O and the Tracys at lunch, her children had disappeared. She went to the phone and called her sister-in-law, the Mayor’s wife. She explained the situation.

“If you wouldn’t mind dear, taking a look down at the pond. They might be looking at the swimmers. And just drive along the main street in case you see them. I’ll send the boys down on their bicycles, if you don’t see them in fifteen or twenty minutes.”

********************

“Now you take water.”

George Wiseman was talking over the pasture fence to Professor Cart.

“Them geologist fellows from Tronna can measure and survey and take samples all round the place, but not one o’ them can find water as good as a witcher. He’s got his little stick, which don’t cost all that money and taxpayer’s money at that; and that little stick tells him just where he should put the well. And most of the time it tells him right. How do you explain that?”

“I can’t. Some people talk about magnetism, but we don’t usually think of magnetism between water and wood.”

“Now tell me if I’m wrong. But it’s generally held that the moon causes tides?”

“Yes.”

“Now if that moon, so far away, can pull all that water around, why can’t a pile of water under the ground pull a little stick?”

“I agree that we should at least be open-minded.”

“Now Professor, you take water. Water is a mighty funny thing. Scace’s Hill is full of water. Scace’s well has never gone dry, and down there in the cedars, why old man Scace had to pour loads and loads of dirt in, and the quicksand still has to be fenced off to protect the cattle. And the oil drum he set in the quicksand never empties of water. Can you explain that?”

“Well, there is a catchment area.”

“Yes, a catchment area over the hill. But now I hear tell from Hans Erkelens – leastwise from Truman McQuoid who had it from Hans, and Hans had it from some fella at the Triple O that all that land those city fellas bought at the foot of Scace’s Hill is absolutely dry. Not a drop of water to be had. Not even in the water courses. Now, how do you suppose that could be?”

“It does sound strange. But water doesn’t always run downhill, you know.”

George looked at the Professor with his head on one side, and repeated,

“Not downhill?”

“On the outside of a hill it will always run downhill. But inside a hill it is governed by the rules of hydraulics, which is the system by which water runs in pipes or a town water system. Pressure in one part of the hill can keep the water table high in another part of the hill. And these pressures and vacuums which control the water depend on the rocks and soils found in the hill. Limestone country, quite different from this, of course, has vast underground caverns full of water. This kind of glacial formation has clays and gravels which form water barriers or great sponges which soak up the water.”

The Professor leaned down and picked up a smooth pebble.

“When your plough turns up even one of these little stones, it may be the first time that stone has seen daylight since the glacier passed over that pebble and carved that pebble into a smooth shape by the action of water and ice and other rock. So down underground there are clay and rocks and sand and mud which have been there all the time. Some of the water itself down there is still chilly from the deep frost of the glacial age, and it may not be released for hundreds of years from now, when someone drills far enough in. Then it will be replenished by water soaking in from the surface. So you see, the water stays up in the hill, but there may be no way for it to get down to the Triple O property.”

“But why should it suddenly dry up down there?”

George’s question was to remain unanswered, for at that moment Bartholomew Cart came running from the field. For once he was not doing play acting and weird exercises as he came.

“Dad! Dad! Mrs. Scace is on the telephone and she says Debbie and Linda are lost. Nobody can find them at all!”

****************

Supper at Scace’s that night was a grim affair. There was no sign of the girls in the village, where news of their disappearance had soon got around. Small groups of people gathered at various places trying to conceal their worry with exterior unconcern. One group of teenage children looked anxiously at the pond, and then beat upstream wondering if the girls could have fallen in. The village’s best plumber and some of his employees delayed going home after a long day to follow the river downstream through the cow meadow which was a kind of inferior village parkland. Telephone calls were made to the prison, to Norham, and to the Ontario Provincial Police. There was not much stir in Norham, but the poultry farmer drove over to Norham Pond and looked at the dam and the marsh, all without result.

The O.P.P cruiser had been sitting in Morganston when the radio call came in. The two officers cruised slowly up County Road 25 towards Warkworth, looking carefully into the fields on both sides of the road as they went. Then at the Norham crossroad, they turned off and went parallel to the Salt River passing “Cartagena” on the way, just a few minutes after George Wiseman had driven off on his tractor and the Carts had gone indoors. The police drove on up the back way to County Road 29, and then came quickly down to where the rambling Scace homestead decorated the brow of the hill.

They arrived just fifteen minutes after Albert had returned home. Thelma had given him the news and gone over all the possibilities, and the boys had given a detailed report on their search. In all this Thelma was calm, but increasingly worried. But when the police arrived, and after she had given her story, she could no longer keep up her valiant tearlessness, and went upstairs to weep on her bed. She was followed by Brian, who brought her water to drink and lay beside her saying nothing. The police drove off, and Albert and Kevin turned on one another in rage, their usual reaction to stress.

“This probably wouldn’t have happened if you weren’t so nasty to your sisters and they could have had a lunch at the house as usual. I heard all about that row you had with them yesterday, you should be ashamed of yourself!”

“It wasn’t my fault! The girls pick on me all the time and you take their side. You never listen to me!”

“Don’t you talk to me like that! You know perfectly well there’s no excuse for the way you carry on at your age with the children – and girls at that – younger than yourself! Now get out and start looking all over again!”

Kevin stormed out the front door, his hair blazing in the sunlight. It was still long before midsummer sunset, but the sky was suddenly red. He saw a flowerpot on the porch and gave it a violent kick, watching it fly down the steps and spill the plants and earth. Then he burst into tears, spluttering all the four letter words he could remember, and some nobody had made up yet, and limped off, nursing the toe which had felt the full shock of the kick.

It wasn’t his fault! The girls had been told not to wander off, and he had not been anywhere near them. They couldn’t – shouldn’t – blame him all the time! But they did anyway – he hated them! Daddy with his bad temper and quick words and Mummy who was so cool and bossy, but who was upstairs crying like a baby because of her precious little girls. He hoped they were both dead!

No, he didn’t. He stopped by the barn. He didn’t hope they were dead. He saw for the first time that he really loved them, remembering how cute they had each been as babies, and how much like puppies or kittens, but so much better, and how he had been jealous of their grace and loveliness. He hoped they weren’t dead. It was his fault! Not that he had anything to do with their being lost, but it was his fault for hating them and wishing them dead. There were funny things in this world that sometimes happened if you were unlucky: your secret inner deepest wishes came true, and they wouldn’t have if you hadn’t wished them.

Or, perhaps, it was his fault, not only wishing them dead, but what he had done with the toy village. Perhaps they had found out and been so unhappy that they had drowned themselves in the pond or the river. He had heard his mother talking to someone about draining the pond to look for them… He could see them, piteously lying at the bottom like dolls, stained and bedraggled and smelling of slime, broken bottles around them.

He ran off into the field, forgetting his limp, and wailing aloud.

Drumlin Fever is now Available for Sale

Great News! Drumlin Fever has now been published. (Sept 2020)

The cost is $20 + $8 shipping and handling if delivered within Canada.