The Topher

by Graham Cotter

A Dish of Milk

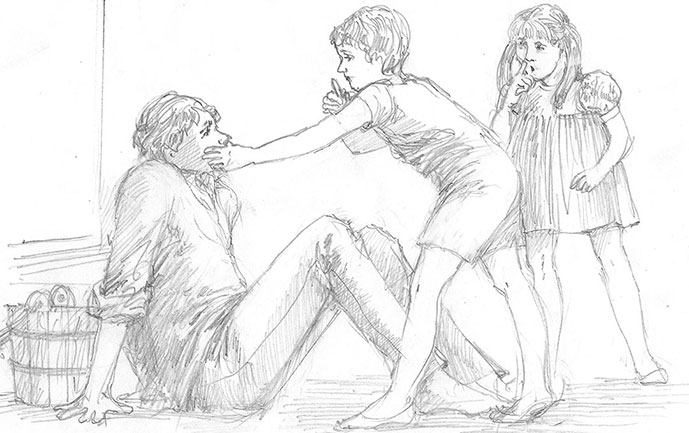

Illustration by Audrey Caryi

After this, the two girls and the Topher rode silently and soberly back to their home at Scace’s Hill. The Topher agreed, as was already decided between the two girls, that they would not take Mrs. Scace into their confidence. It was not that he lacked faith in her ability to understand their bizarre adventures — though he only dimly understood them himself; rather, the matter was so very personal and private to him, his own private world, that only the girls’ apparently accidental — maybe providential — intrusion through their time travelling had persuaded him to confide in them.

There were just too many unanswered and unanswerable questions about the whole affair. Even if Mrs. Scace did not prove to be a scoffing rationalist – and he was sure she was not the opposite, a respectable conformist – he would be very uncomfortable reciting his part in the events. Besides, she would be sure to tell her husband and he was an unknown quantity.

So the trio were rather quiet as they accepted Thelma’s icy cold lemonade and some biscuits. She wondered why they were so quiet, but decided it was the hot day and the exercise. The girls arranged to see the Topher again, meeting him at Warkworth for “more bicycle riding” the day after tomorrow. He pleaded that tomorrow he must stay quietly by himself and do some study, by which he meant thinking. Thelma offered him the loan of her bike during his holiday — she wasn’t

going to ride much in the heat. He gladly accepted this, saying that he really enjoyed riding with her girls; they were such interesting companions, and had such interesting adventures to tell about, both real and imaginative. In reality, he knew, he must see more of them, and reawaken his dreams, even if they were now daytime occurrences, and hardly ever happened when he was asleep.

At Scace’s Hill, the rest of the day passed normally. Both girls helped sort the laundry and get the supper, and they greeted their daddy cheerfully as he arrived after a hot day touring the conservation projects. After supper they helped hoe the garden as the day grew cooler, and at dusk were allowed an hour of television. They watched two American programs, a humourous one about bigotry and a humourless one about police catching the leader of a dope ring. And so, suitably refreshed, they went to bed.

Thelma gave Albert an account of the Topher. He listened in silence,

apparently not worried that his children had an older and somewhat eccentric friend. Then he asked questions about where the Topher had camped, and noted that he must go and meet the young man, perhaps enlist his help in checking some of the water levels and erosion problems in that little used area of the river course.

Then Thelma asked,

“Albert, did you ever tell the girls about the old Curtis place down at Norham?”

“You mean Sugar Grove?”

“Yes, up behind the Township Works yard.”

“No, I don’t remember telling them about the place, why?”

“That’s where they were today when I checked on them. Seems they and

their gentleman friend are very interested in local history. I wonder where they heard of Sugar Grove?”

“Maybe they learnt about it in school. That minister’s wife from Hastings who teaches is full of local history.”

“Maybe.” Thelma pondered.

She couldn’t get it out of her mind that the Topher seemed to belong in the countryside, but had never before been here.

The girls meanwhile were whispering together. Debbie now accepted the

shuttle back and forth in time as though it were commonplace. It was after all, no more extraordinary than stories she entirely identified with in books or on TV.

“Lindy, do you like John as much as the Topher?”

“How could I? I hardly know John,” Linda replied sharply.

It was bad enough having to put up with Debbie’s always coming back to sex with “love” or “like” but here she was accepting their experiences as a subject for gossip. It just seemed improper.

She went on:

“I’m trying to figure out what it all means, aren’t you?”

“It means we have two big boyfriends,” giggled Debbie.

“Did you understand what the Topher said about his dreams about John?”

“And about Martha? No, I don’t suppose I did.”

“One thing, Debbie.”

“What?”

“The Topher needs us to get back to what John is doing.”

“To get back so’s he can see Martha again, I think.”

“What I can’t figure is, can we go back anytime we want, or must it just happen?”

“Gee, if it hasta just happen, it could happen anytime, when I’m sitting on the john or having a bath! That would be awful!”

“Debbie, be serious. It’s got something to do with people looking for

something. We went looking for Drumlin Hill, we went looking for Hairy Hippies, we found the Topher, — he was looking for his dreams to come back, and when we went with him looking for Norham, we found his dreams, and John found us. But

the Topher is still looking for Martha, and I guess John is still looking for us, in a way.”

Now Debbie did turn serious, and said to her sister,

“Look and ye shall find.”

“Seek and you shall find.”

“Seek — as in Hide and Seek?”

“Yes, it means to look for.”

“This going back is like Hide and Seek, isn’t it?”

“Yes.”

The girls were quiet for a while.

“Lindy?”

“Yes.”

“I just thought of something.”

“What?”

“John lives — back whenever it was — in Norham, doesn’t he?”

“Yes.”

“His own house, his daddy’s house, is somewhere else, not the house we saw today?”

“Yes.”

“Well, we hafta go back and look for him there.”

“Why?”

“Because he had seen us before, he knew us today and spoke to us. Is that it?”

“Yes.”

“That’s pretty clever, Debbie. I think you’re right. But where?”

“I dunno.”

Debbie yawned.

“G’night Lindy.”

“Hey, Debbie! before you go to sleep — we get up early and go look, before breakfast.”

Linda’s voice was urgent.

“Okay, Lindy, whatever you say.”

And Debbie was asleep.

So it was that the next morning they were up before the sun. They slipped on rubber boots and jeans to keep the poison ivy off, for they were going to take the short cut towards Norham, directly down the road allowance which ran beside their garden gate. At one time the road had been used, perhaps more in the winter than the summer, for the hard snow and ice were easier for a cutter and a horse in the old days than the sandy soil towards the bottom of Scace’s Hill for a wagon and two horses in spring or fall. The sands stretched on at either side of the road for some distance. They were remains of the beach of Lake Iroquois, that post glacial lake which covered the whole Trent Valley, and lapped up against the foot of Scace’s Hill just as it also lapped against the foot of Gallows Hill in Toronto, below St. Clair Avenue.

Down they plunged, brushing aside the tall weeds, the mulleins with their spires of tiny yellow flowers five feet in the air, the five fingered ivy reaching down from the trees and the wild grape reaching up from the shrubs. They didn’t pause, but rushed along the rough path which they and their brothers and their friends had made over several years, past the entrance to their toy village, past old rotting stumps and deadfalls which would have kept their brother Brian fascinated for hours, and past the culvert where a strange adventure had begun for Brian earlier that summer.

Now they were at the sandy flats, really on a level with Norham itself, but with a mile of road to go before the scattered villages would be in sight. For now a real road appeared, and it was this same road which they had taken from the highway to go to Norham on their bikes yesterday. It came as far as the flats, because people like to go there to collect sand.

Here they hesitated. They didn’t really know where they were going, for they did not know where John’s home had been.

“Which way, Lindy?” said Debbie, her wide eyes all trust and innocence.

“Do you remember that grown-over place, over there, at the edge of the flats?” said Linda, guessing wildly to justify her position of leadership reinforced and depended on by her sister’s faith.

“Uh, Uhh, I think so.”

“Remember, we played Fort there with Brian and Kevin and Bart Cart one winter?”

“Yeah, that was fun, till that meanie Kevin put snow down my neck.”

“Yes, well, you got your own back with your scream. Mr. Wiseman heard it and thought it was the fire alarm whistle in Warkworth.”

“So he said, but he always teases me.”

They were scrambling along the sand flats when it happened.

*******************

It was before dawn, in April of 1838, when the boy John stirred the fire. The log house was chill and damp, for the fire was kept low overnight as spring drew on, and was used only for cooking the hot meal of the evening. Sometimes it was John; sometimes it was his father who cooked the meal, since John’s mother had died in the winter.

John still found it hard to sleep: he expected to see his mother all night long. She would surely have a message for him, or some comforting thing to tell him, if all that she had taught him were true, about death. Whenever Church meetings took place, he found an excuse to go, hoping to find out more. When Reverend Stuart Harper, Church of England pastor, had come through on his big black horse,

John had held the bridle, watered the horse, listened to the sermon. He had even sneaked off one day to watch the goings on at the papist chapel and though he either didn’t hear or didn’t understand every word spoken, he liked the colour of the priest’s robe. But it all had been very unsatisfactory, and his father didn’t approve of his making visits to Norham village, to the mound which covered his mother’s body.

“No time in your life to be pining over your Mother. I miss her too, but I can’t bring her back.”

Last night though, he remembered something. It was from way back, when he was small. Since before he first saw Martha, he thought. He sobbed as he thought of Martha, for he’d been so upset by Mammy’s death he couldn’t bear to call on Martha, and he was afraid that he’d lose her too…. He remembered his Mammy had talked of the Little People, how they were shy and never showed themselves, but if you wanted a great favour of them, you… what was it you did?

Something to do with a cow. Yes, you went to a cow at midnight, and you took a pull of milk from each teat, moving always to the right, from one to the other. And the milk must go straight in a bowl which hadn’t been used for a day, and you must not see the milk to look at it, but walking holding the bowl to one side, not looking at it, and place it on your front step, never spilling a drop. And you must go straight to bed yourself, wishing for what you wanted. With luck, in the morning the milk would be gone, taken by the Little People, and you’d get your wish. But you must never try to catch a glimpse of them, or they’d never come again.

So John had gone through the ritual, hoping that the bowl he picked had not been used. He had taken great care, and never spilled a drop, nor seen the milk. Just to be sure, as he went to bed, he knelt in prayer, to both God and the Little People to grant his wish. It was only as he woke that he realized he had forgotten to tell either God or the Little People what his wish was. He rose up shivering, pulled a fur off the bed and around him, and stirred the fire. Across the room his father was still sleeping heavily, having topped a day’s hard work with a night spent at Stone’s Tavern with his friends.

Just then, John heard voices, light and tinkling voices, outside the door. Children? he thought and opened it a crack.

“Glory to God,” he said, “It’s the Little People.”

There they were, one fair headed, the other red headed, both about four feet tall, both in great shining boots such as he had never seen, both in green trousers, and shiny red blouses, both laughing and excited running towards the house.

“John, John,” they cried, “We’ve found you!”

“Shhh, ye’ll wake my Pap,” he said, closing the door and emerging wrapped in his fur.

Then amazed by his own boldness, he whispered,

“Begging yur pardon, Sirs, please don’t go away forever, I never meant to see you I thought you’d have drunk the milk in the night.”

“Drunk our milk?” said the Little People, both at once, astonished.

With this poor John went down on his knees, and his knees went straight into the bowl of milk. The Little People’s reaction was not to disappear for ever, but to double up, one hand on each stomach, and one on the mouth, and dance around in a circle, making little squeaks and gurgles as they did so. If only John had only known, they were laughing; it was as well he didn’t, for they were laughing at him. He, in fact, was sobbing again. He didn’t seem able to get anything right, and he’d upset their milk.

“Please,” he said, “Wait right here and I’ll get you fresh milk from

the cow.”

He scrambled to his feet, the knees of his britches wet with spilt milk.

“John,” said Linda, “Wait. You mustn’t cry over spilt milk.”

“That’s right,” echoed Debbie, “no crying over spilt milk.”

“Oh, Sirs, I beg your pardon. Is it worse to cry over the spilt milk than to have spilt it — or to have seen your milk I poured for you – or to have seen you indeed?”

“John, who do you think we are?”

“Oh, saving your grace, your graces –”

John was trying to think of polite things he had heard said to important people.

“You’re the Little People, and thank God for that.”

“The Little People?”

“Yes, your graces, and I did as Mammy told me, about the milk. It’s my great regret and eternal (he said ayetayrnul) sorrow that you have not had your milk.”

“You poured milk for us?”

“How did you know we liked milk?”

“And how did you know we were coming?”

“I knew — for that’s the way — to make the Little People come.”

John sat down on the ground with the effort of talking with these supernatural beings from another world, as they seemed to him. Linda and Debbie set him at ease by squatting beside him as he seemed uncertain about whether he should sit in their presence.

“Isn’t that how ye knew I wanted ye?” he said, recovering a bit. “How else would you know who I was?”

“We knew because we saw you — .” started Debbie, but Linda poked her, and interrupted.

“We wanted to help you so we came. And it doesn’t matter about the milk. Some other time.”

“Oh, you mean you’ll come again.” said John brightening.

“We will,” said Linda, “till we’ve helped you find what you’re looking for.”

“Oh, glory to God! then I’ll see me Mammy again!”

“Sure, you’ll see your Mammy,” said Debbie, “Where’s she gone?”

“That’s it, where’s she gone?” asked John, on the point of sobbing

again. The girls looked at him intently.

“Toronto, perhaps,” said Debbie, trying to be helpful.

“Tor -ron -to, tor – ron – to,” said John, savouring the word. “I’m not sure just what that might be. Is it like Heaven, with the good Lord, or Hell, and the damned souls?”

“Oh, it’s a city, where we come from,” said Debbie cheerfully.

“Then glory!” said John, jumping up, “me Mam’s gone to glory!”

Linda stood up and held out her hand, holding his sleeve.

“John,” she said, “Is your Mammy dead?”

“Yes, me Mammy’s dead and perhaps she’s gone to Tor-ron -to, and sings there with the saints!”

“John, we can’t tell you these things,” said Linda, trying to remember what she’d learnt at Sunday School. “but we have come to help you. You must tell us what you need.”

“Oh, Little People, I may not need anything now, for I’m so happy, ye’ve made me so happy. Now I can visit my Martha again.”

“Ah, Martha,” said Debbie, “She must be beautiful. Our friend told us she’s beautiful.”

“Debbie,” said Linda, “I think you should not mention our friend. What he’s told us is privileged information.”

“Sorry, Linda.”

“Oh, Sirs, begging your pardons, but your friend is right: Martha is most beautiful, she’s my wild raspberry rose.”

“Then why haven’t you visited her?”

“I was too sad, with me Mam dying like that. I wanted to die too.”

“That’s just like a selfish boy, sitting around thinking about himself. What would poor Martha be feeling, you never coming to see her? Didn’t you think of that?”

Linda felt very grownup, giving grownup advice.

“Oh, my poor Martha, I never thought how you would feel!”

“Yes,” said Debbie, ” She might not let you kiss her.”

“Oh, I’ve never done that! That would be a terrible thing to do!”

“Why so?”

“To kiss her, why that would be against the Bible, and worse, her father would beat me, and my father would beat me!”

John was appalled at the suggestion.

“Anyway,” said Linda, trying to move off a dangerous subject, “you must go to her as soon as possible, and tell her you’re sorry you neglected her so long. Those are our orders.”

Linda realized that as Little People, whoever they were, she and Debbie had considerable authority over this boy. It was a lot more comfortable than being a ghost, at any rate.

“Oh, I shall, I shall do so, and I shall say that the Little People have appeared to me and that my Mammy is in glory in Tor -ron-to!”

“No, John! You mustn’t. You must tell no one you have seen us. For even if anyone were here now, she could not see us, though you can.”

Linda knew that much from her experience in seeing John at the Curtis house, earlier; no, she thought, later on in John’s time, at least. But she instinctively knew that, just as she had not told her mother of these adventures, so any one who knew of them must not tell his friends either. She wasn’t quite sure why, but she knew there were enough complications keeping track of time and people as it was.

“When you’ve seen Martha,” said Debbie, talking without thinking much, as usual, “then perhaps we’ll see you again and help you with something more you want. Lindy, I’m hungry.”

“Oh, Sirs, I have offered you milk -”

“No, John, we have – a banquet to attend. We must soon depart.”

The words seemed important enough to go with the obvious importance of Little People. Just then there was a roar from inside the house.

“Boy! Boy! Who are you talking to out there?”

“Oh, Pap! It’s great news!”

Linda rushed up and held her hand over his mouth.

“Remember John, don’t tell a soul, not even your Pappy.”

John’s Pappy appeared at the door in trousers only, his big feet bare, his chin dark with beard, his eyes bleary.

“You fool of a boy talking to yerself like a madman!”

“No, Pap, I’m off to milk the cows.”

John turned and made faces at the Little People, not daring to speak to them now. Just as he realized fully that his father could neither see nor hear them, there was a shrill beep from the walkie-talkie, which Linda had crammed in her pocket at the last minute. John’s hair stood on end, his eyes grew large, he staggered back and the Little People disappeared.

Linda and Debbie were standing by a mound of earth near the edge of the sand flats, and Linda hastily turned on the sender to tell her mother they were hurrying home to breakfast.