The Topher

by Graham Cotter

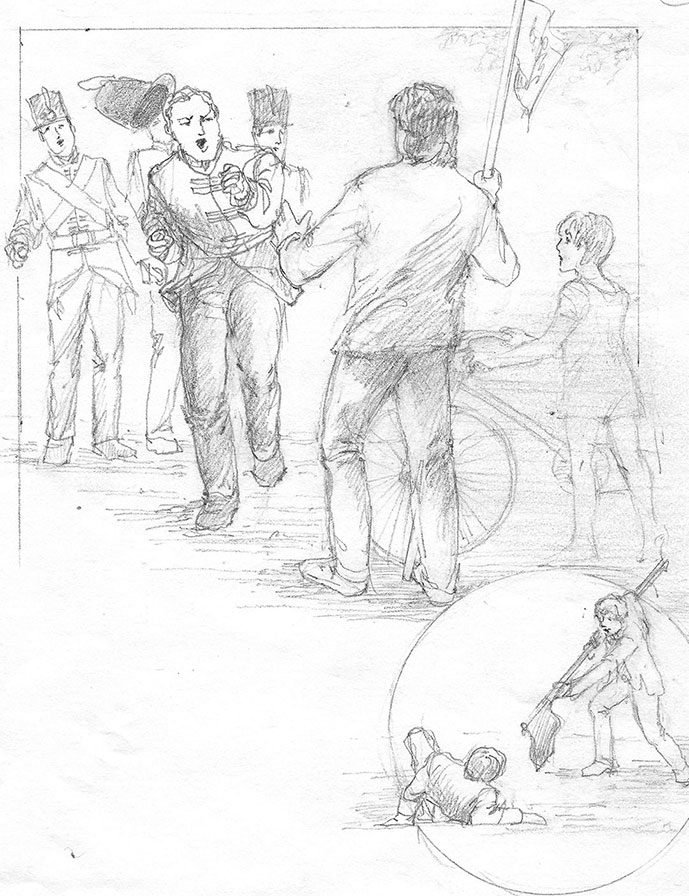

St. Paul Appealed to Caesar

Illustration by Audrey Caryi

The Major rode back to the ranks, leaving his officers.

“What kind of soldiers are you! Telling your officers what to do? You’re as bad as any rebels can be, worse, mutinous. Not a word from you on that. It is my commands you must obey and none other. And I tell you,” drawing a great breath, “There is no rebellion here. These farmers are met, perhaps in unlawful assembly, to appeal to the Governor for political reform. Lord John Lambton, Earl of Durham, is of the greatest English nobility! Would you fire on his name! We must respect it and his office.”

“It is a wile of the devil, Major,” said the Sergeant. “They appeal to this English Lord to confuse us. They mean rebellion!”

“Sergeant! stand back, or I’ll put you on charge!”

The Sergeant looked around ready for the first man who would obey such an order from the Major. His breath heaved in fury, so divided were his loyalties.

“Sergeant! And men! You are God-fearing folk. Remember, St. Paul appealed to Caesar. Such an appeal as in Bible days must be heeded now.”

“You’re no comparing that devil Comfort Curtis with St. Paul!” said the Sergeant, aghast.

“As to that Paul, I know what I’d a’ done with him,” shouted Giles Stone, looking indeed like Nero.

“As God is my judge, and the Queen my Sovereign,” said the Major, drawing his pistol with his left hand, “I’ll shoot the first man or officer who fires on these citizens. If they fire on us, it will be rebellion, and then there will be cause. Let no man disobey orders!”

“Debbie,” said Linda, “Tell John the Major won’t let his men fire unless the rebels fire first.”

John passed the word on, in turn, but Comfort had already assessed the situation. He could not hear a thing the Major said, but some of his scouts had returned. The word soon spread among the farmers that their appeal to Durham was working to demoralize the militia.

The temptation was too great. Even the armed men on the ground leaped up, and joined in jeering the redcoats. Personal insults began to fly.

“You, Irish Kennedy! It’s not the law you want, but your damn tollgate on the road.”

“Stone, you fat pig! Where are your high prices now?”

“And spoiled flour sold as good?”

Stone replied furiously, pouring out his hate on his brother:

“Jerimias, ye drunken sot, I’m ashamed I shared the same home with ye. Father should have drowned you when you were born!”

“We had the same home but not the same mother! God knows who your mother was – or your father either!”

Jerimias could give the insults too, and knew what would hurt his raging brother.

“Better turn around Major! Before them damn Tories shoots you in the back!”

“That’s all they’re good for, stabbing in the back when an honest man suspects no harm!”

“Ye radical swine! We’ll skin the lot of ye, and hang your backsides out to dry!”

At the word dry a great flash broke out across the sky. For a second Linda thought a shot had been fired, then there was a roar of thunder, another flash, and crash after crash of thunder drowned out all insults. The two sides stood in astonishment, their mouths agape, wondering too if the battle had begun. Then they had the answer: the rain came, no ordinary summer rain, but a violent thunderstorm rain filling the road in no time, wind lashing the rebel banner down on the heads of the farmers, wetting the powder of the musketeers.

The farmers, without order, went for shelter in the Inn or the Chapel, wherever they could fit. The ambush men went into the nearest houses. Only the militia did not break ranks, but looked piteously at the Major. The Major, who had a greater fear of lightning than of bullets or war shouted out his order.

“Company! About face! At the double, run. Take shelter in the barn at Sugar Grove!”

The Major galloped to the other end of the column and with the other mounted men, raced towards the barn. The drummer followed trying to beat a march, but with his drum soaked and the thunder bellowing, the winds screaming, he was not heard. The company followed too, all but the two Cameron brothers and about ten of the well-trained men who were ashamed to turn tail before the rabble of farmers, even in a rain storm. They stood clustered and dripping in the road.

Linda was uncertain which way to go. If she stayed with the Major she could report any new plan for attack that would develop. But the small group of disobedient soldiers were the most immediate danger to John and his friends. Yet they were close enough to the tavern for the people sheltering there for Debbie to keep an eye on them.

“Debbie?”

“Yes Lindy?”

“Where are you?”

“In the Tavern. It’s fun, but people keep falling over me.”

“Come outside and see what happens.”

“It’s too wet!”

“Go on. You must be soaked already.”

“Okay. Nancy and Out.”

Debbie didn’t know what would be going on outside except the storm, but she gave in. As she came out, the rain abated a little, and she could see, up the road, the small knot of militia forming up. All were armed with guns, and some with pistols and knives. They were spread out in a line and were coming slowly down the road, ready to fire at the first rebel they saw. She could just make out Linda and her bicycle beside them, for they had formed up while the two girls were talking.

Linda’s voice came over the radio.

“Debbie! Quick! Call John!” Debbie rushed inside and, not worrying about whether she puzzled or annoyed the crowds in the tavern, leaped over and through them to John.

“John, quick, tell Mr. Curtis some of the soldiers are still coming!”

John shouted out to his future uncle-in-law and in a moment the whole tavern was in a turmoil as everyone set about finding his weapon. John made his way to the door as best he could, and there, awake from the commotion of the last hour but now rested, was Martha.

“John dear, I’ve something just for you. Take it for me, and wave it at those redcoats, and God bless you and bring you back!”

It was a white sheet about a yard long each way, and on it in bold red letters, was the word “Liberty” with what looked like a great bird below it. It was a bird, the best Martha could do to embroider the American Eagle, and it was what she was doing while held captive by the Camerons in her own home the night before.

“Good, that’ll show what we mean!” said John. Turning, he grabbed a musket with the bayonet from a dazed farmer standing by, and slit the sheet in two places, so the musket acted as a flagstaff. Shouting “Liberty for Canadians! Freedom for the people!” he ran out into the rain waving his flag above his head.

Already there were twenty or so rebels outside, their guns aimed at the advancing soldiers. The advance had slowed down as the farmers came out again, and now six soldiers knelt to take aim, while the others stood behind, their guns ready to shoot.

Linda in the meantime had sped on her cycle – as much as any bicycle could ‘speed’ on that rough road – back to the barn. Major Campbell must be fetched, she did not know how, but somehow he must come and stop his men. The horses had been tethered just inside one end of the barn. Linda looked desperately about trying to think what to do.

At that moment a shot ran out from the direction of the tavern. The temptation of John’s American Eagle had been too much for the Sergeant. He had put a shot right through it at close range. The two lots of armed men faced each other paralysed with fear and anger. Even above the noise inside the barn the Major and his men heard the shot. The Major raised his voice:

“Stay where you are! Your orders are to remain here till the storm is over. I shall go and investigate this shooting.”

Sooner than he thought. The horses were very perceptive of the strange creature who came unseen amongst them. In the intensity of the advance down the road, they had been attentive to their riders’ orders and needs. But now, loosely tethered, they were aware of Linda; it was as though they could see her. They whinnied and reared, snorting in fear.

Linda, who had grown up with animals, fearlessly went to the Major’s white horse, held its bridle, and patted it’s nose. It stopped, for a moment too startled to move. She pulled it out of the barn and ran, the unwilling animal rearing and kicking behind her. She rushed up the ramp landing into the barn, and the soldiers had a vision of a panicky horse, its bridle held out at an angle before it, coming unwillingly and jittery in through the door.

Linda went straight to the Major, smacked him on the cheek with the bridle, pushed it into his hands, and fled to the door. At that moment a peal of thunder echoed in the distance.

“Glory be to God! A sign from heaven!” whispered an Irish military man.

The Major, whatever he made of it, needed his horse then as badly as Linda needed her deserted bicycle. He leaped to the saddle, and went out the door, galloping down the road to the scene of battle.