The Topher

by Graham Cotter

The Northumberland Militia

Illustration by Audrey Caryi

The next day, by pre-arrangement, the two girls met the Topher at the BeeHive in midmorning, where another round of ice cream cones was in order. Then they set off on their bikes towards Highway 30, travelling due East on the county road. When they reached the highway, they paused briefly before turning back. They could serve no useful purpose by going further, and they really wanted to double back towards Norham. That was where the excitement lay.

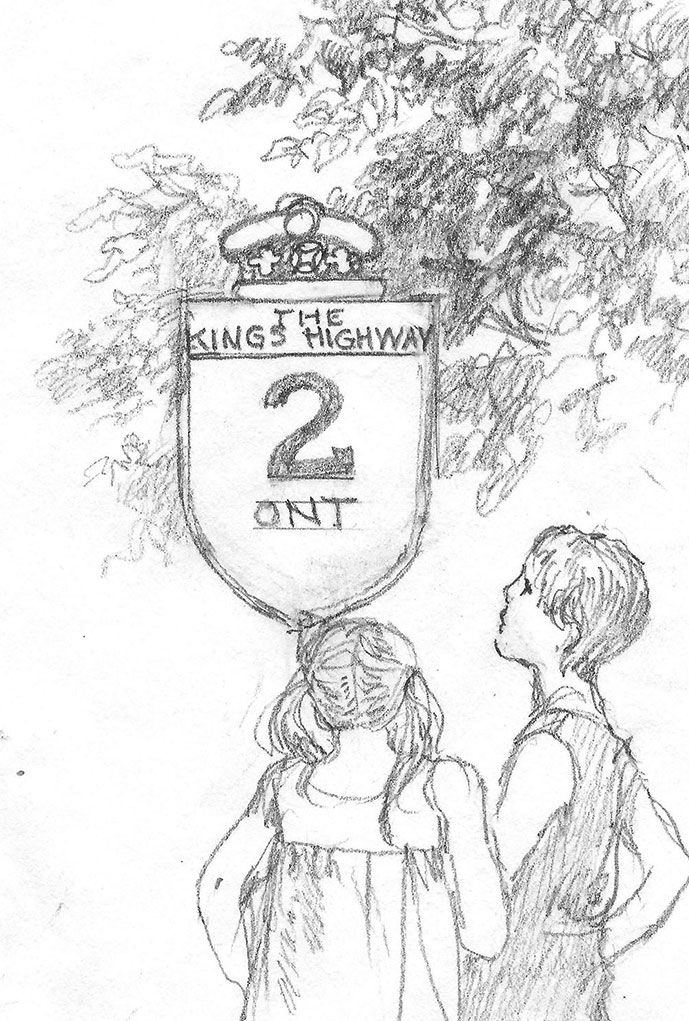

Debbie looked at the Ontario Highway sign; a shield, surmounted by the outline of a crown, the number of the highway on the main body of the shield, and the words “The King’s Highway” over the numbers.

“Why is it called the King’s Highway?”

“Because,” ventured Linda,” It belongs to the government.”

“Well, I suppose they had these signs left over from when there was a King — wasn’t there a King before the Queen?” she looked at the Topher.

“Yes, I guess so. I wasn’t born then.”

He didn’t seem much interested either. He was a bit withdrawn today, not saying much.

“Lindy.”

“Yes, Debbie.”

“Remember what happened at Drumlin Hill?”

“Yes.”

“Remember we first noticed the rough road and the logs?”

“Yes.”

“Well, that was corduroy, you said it meant the King’s wood; maybe this is the same thing, only now it’s the King’s Highway.”

“I suppose you’re right.”

“Okay girls,” said the Topher, “shall we go back now?”

So the three turned back, went past the golf club, and found the turn off to Norham. There was an abandoned schoolhouse right at the junction, and here they put their bikes under the lilac trees and sat down. They had promised the Topher an account of their encounter with John when they met him at the BeeHive, and now was their opportunity. Linda told the story, with interruptions from Debbie.

“What do you make of it, Topher?” she asked, when the recital was over.

“Well, there are a lot of interesting developments. I’ll try to sort them out in my mind.

“First of all, we both see things that happened long ago, but you actually seem to go back there, where I see things through John. And we both, now, can go back and see things.”

“Lindy, do you remember what you said to me before I went to sleep night before last – about wanting to look for something?”

“Yes. You see, Topher, I have this idea that this happens because we are looking for something, and we go back to John, and he can see us, because he is looking for something.”

“Then if you are looking for something, and he is looking for something, we should be able to decide when we can go back and meet him.” He stopped.

“Maybe… but we can’t decide, from our end, just in what part of his time we will arrive there. We’ll arrive when he needs us.”

“Seriously, Topher, how can it happen? Is there really time travel?”

“I don’t know how it can happen, but you can see for yourself you are going back in time.”

“On TV, you get into a machine for time travel,” said Debbie.

“Yes, but there’s no machine here.”

“There is one thing though,” said the Topher.

“What’s that?”

“Well, you don’t travel in space. Maybe you don’t travel at all, but John’s time comes back for you. Or comes forward to you.”

“Hide and Seek… makes sense” said Debbie.

“Oh, Debbie!”

“Well maybe she has something. The past is hidden, and we seek for it.”

“Or, it looks for us. John was looking for news of his dead mother.”

“But he didn’t really find out about his Mammy. Where she’d gone when she died.”

“He thinks he did, and that helps him for now.”

“Do you notice,” said the Topher, “how we can’t really talk about John’s

time as past, not all the time?”

“Yes”

They were silent for a while, then Debbie spoke up.

“Who are the Little People?”

“Well,” said the Topher, “Probably John, from the way he talks, and many people about Norham, come from Ireland or Scotland, or his mother did. The Little People were part of the fairy-tales of those countries. They were supposed to be able to help you, or cast spells on animals.”

“So he thought we were them?”

“Yes.”

“Gee, I’d like to be able to cast a spell,” said Debbie.

“You do.” said the Topher, winking at Linda.

Linda was not sure she found Debbie so funny, so she went on.

“You said that we had to be in the same space place. So, if we were in

Toronto, we couldn’t meet John?”

“Not unless you met him at a time in his life when he was in Toronto.”

“That silly John seemed to think Toronto was heaven or something,” said Debbie.

“Say, yes, that was funny. How come he didn’t know about Toronto?

“Well,” said Topher, “Toronto was an Indian word meaning something like ‘portage’, or where you had to carry your canoe between rivers. Lake Simcoe was once called Toronto, and so was Port Hope. Depending on when John was talking from — what year it was when you met him — what we call Toronto was probably known as York. In any case, John probably didn’t know much about the world outside Norham and Percy.”

“How come you know so much?” said Debbie, teasing.

“Mary tells me a lot of this. She works in a library and can never finish reading books, she gets into so many.”

“What’s she like?” Debbie’s voice was pleading.

“She’s tall — not quite as tall as I am, but taller than your mother. She wears her hair back in a ponytail, and glasses. She likes keeping everything in place.”

“Including you?”

The Topher laughed.

“Yes, I guess so. She’s right for me. Cheers me up when I get down, and she’s always sensible.”

“Topher,” put in Linda, “What do you get down about?”

“Oh, this John business. And whether life today is worth it. You know. Things bother me. Just growing up and doing what everybody else is doing seems so empty. Government and business seem to run everything, run it badly, and there’s not much you can do about it.”

“Stuff like Watergate and the President resigning?”

“I suppose so. Though the States seem far off to me. Enough of a mess in Toronto. I don’t need to think about American politics.”

” ‘Merican politics certainly bothers me,” said Debbie. “I missed a whole lot of my favourite programs with all those crazy people talking about Watergate.”

“But Debbie,” said the Topher, “Even you can’t forget about politics. It looks as though John is getting deep into some old Canadian politics, and you like him.”

“And I like you too, Topher.” She giggled.

They were silent for a bit, as they compared the past and the present. The Topher was thinking about John. Linda was thinking how strange life must have been when a boy in the country would never have heard of Toronto, just a hundred miles away. Debbie was thinking what a lovely warm day it was, under the lilac bushes, with their heart shaped leaves looking so friendly.

Then she heard a voice: “Major Campbell., Sir.”

“At ease, Sergeant Cameron.”

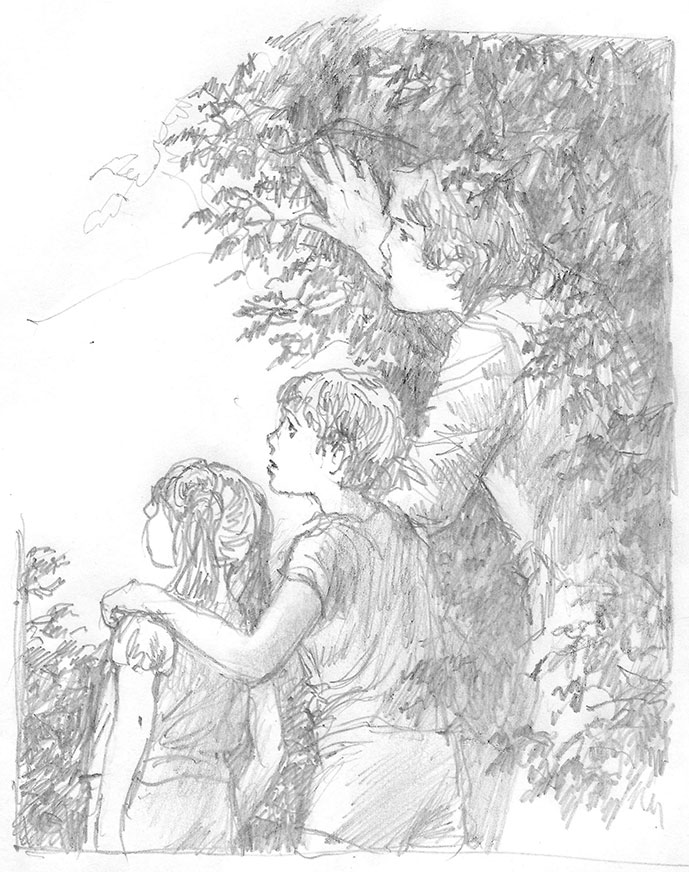

“Militia Company reporting correct, sir!” There was a stamp of heels, and the sound of marching. Debbie looked harder at the lilac. It seemed just the same, but there was a break in the bushes she had not noticed before. Gingerly, she rose up and peeked through. The little knoll where they sat overlooked a cleared field — almost cleared, that is. There were still stumps here and there, and some glacial boulders. In between some wheat was growing.

At one side of the field, the side nearest herself, there was a small group of men, apparently soldiers. They were in rough breeches of various shades and states of repair, and they wore topcoats of a rough reddish material. All had bands around their shoulders, cutting across and making an X front and back, and all carried rifles. They were standing very still, in a row, about twenty of them.

The other soldiers were walking slowly along. One of these carried a rifle, complete with bayonet, straight up from his waist, so the bayonet stuck up above his head. The other had a different uniform, with shiny braid at the shoulders, and seemed to have an enormous sword dragging along his belt. She looked furtively behind her. Linda was still squatting where she had been before, but looking up at Debbie, with her finger to her mouth. Where the Topher had been was John, lying full length, but his head well under the lilacs apparently looking out at the scene from lower down. She didn’t think he knew they were there, and she was afraid that if they spoke or moved suddenly, he would shout out as he had done at his house just yesterday. Or, was it yesterday his time?

Anyway, she had a strong feeling that he was seeing and hearing something he was not supposed to. Major Campbell was speaking, or rather shouting, so she didn’t know what was so secret about it.

“Northumberland Militia, Percy County, at ease!”

The men relaxed, but not much.

“Now men, you know why you have been called to arms. As loyal subjects of Her Majesty, and supporters of the British Throne, as men who, some of you, spilled your blood for King and Country against the Bonaparte at Waterloo, you have come together, summoned to arms, to defend Her Majesty’s Colony.”

“But this time there is no outside enemy, no cursing burning, looting, Yankee armies to throw back. This time the enemy is within. You know that they have refused to bear arms in this very militia, as required by law; that they have sympathized with that scoundrel MacKenzie, now outlawed to New York State; that they refuse to pay the road toll, and have set up their own mills to grind corn and saw wood. You know that they are even now threatening to beat up any good citizens who would vote for loyal true blue assembly men who will support the Governor and Council.

“All this you know. What you do not know is that they are at this very time plotting to burn about our ears the houses of those of us who are loyal to the Queen. They have been meeting in Norham, and are preparing to drive us out and set up a republic with Mackenzie as President. We few of the Militia stand between them and their designs, until such time as help shall come from York or Kingston, whichever is first.

“We must therefore be prepared to meet every day two hours before sundown, for military exercises, and we shall meet in different parts of the township, to frighten these cowardly republicans, and make them think again before they rebel against our righteous cause.”

Debbie groaned to herself.

“The Topher was right,” she thought, “it was just politics then, too. But that man with the bayonet is handsome.”

She was referring to Sergeant Cameron, tall and straight and strong, with a shock of red hair like that of her own father, and a fierce red face with a handsome strong nose. By now Linda had risen on her tiptoes to see past Debbie and look at the parade. She whispered in Debbie’s ear,

“I don’t think John knows we’re here.”

“Yes, I do.” came a hoarse whisper from John. “Dear Little People, be quiet, or them soldiers will find me out and shoot me.”

“Never fear John, we’ll not let them do that.”

Linda was not quite so sure how she would be able to keep this promise.

At this point, after some arms drill, the parade of soldiers moved off. They paraded past the point where the watchers were hidden, and back to a rough road which lay behind. Linda realized that this road took the same route as the asphalted road they had ridden along with Topher just a few minutes ago, in her time. Of the school house there was no sign, just luxuriant green lilac bushes.

Illustration by Audrey Caryi

By the time the parade was tramping well into the distance, the three turned to look at one another. John wore a more confident air.

“I must thank ye very much,” he said, “for all that ye’ve done for Martha and me. But I don’t understand why you didn’t come with me to see Martha at the house the other day, and why ye’ve never been back.”

“Well, we weren’t ready to come back.”

“I wanted you to meet Martha, and to tell her all about you, but as we went into the kitchen, you were gone, I know not where.”

“John,” said Linda, “didn’t we tell you never to tell anyone about us?”

“But Martha!”

“No, not even Martha. We have come just to you. If Martha can see us, then we’ll talk with her, and she can be in on our secret. But if we are ever with you when you are with Martha, and you tell her of us, without us first appearing to her, we’ll never come back.”

Linda wasn’t sure of this, either, but it seemed wise to keep him quiet.

“Dear Little People, I do not understand you. At Curtises, and today, you are so strangely dressed. Do you always wear red and green?”

The girls were in scanty shorts and halters. Linda was getting short of invention, so she decided to tell the truth.

“It was very hot where we came from, and we were riding our machines.”

“Machines! So you ride on broomsticks?”

“No, silly,” said Debbie, “bicycles.”

“Byskls! What are they?”

“See, there they are,” she pointed.

A look of great astonishment and fear came over John.

“Wheels.” he said, “wheels like the vision of Ezekiel! You come from heaven upon them.”

He knelt down before the cycles. Debbie went over, and raising hers to its hind wheel, sent the fore wheel spinning.

“Glory to God! Eyes within and eyes without! The vision of the

Prophet!”

“No, John, just a way we have of moving about.” Linda wondered what would have happened if the poor boy had seen a motor car or even a light airplane.

“But sirs,” John’s respect was abject again, “There are 3 Byskls. Do

you need three to ride upon, the two of ye?”

“Another was with us, but you can’t see him.”

Linda decided that was about as much truth as John could stand.

“Now, John, pull yourself together. We are here to help you. What do you want from us?”

“Oh, that you should bring me and my Martha together to be married.”

Debbie giggled.

“That will happen in good time. There must be something of danger to you or something you need for yourself.”

“What about getting shot by those soldiers. You said you were afraid of that,” said Debbie.

“Oh, Sirs, that is true. Master Comfort Curtis makes me keep watch on the Militia. I fear I shall be caught.”

“Will you report to Mr. Comfort Curtis what you heard today?”

“What did I hear today?”

“That the soldiers will parade every evening, silly.” said Debbie.

“Most certainly, and I have to keep watch of the Major’s house. I fear I shall be seen and suspected.”

“What do you do?”

“I stand across from his house and look at it.”

“In broad daylight?”

“Every day till I return for my dinner.”

“Hasn’t the Major noticed you?”

“Yes. He says, ‘Hullo boy, why are you hanging about’.”

“So what have you replied to him?”

“Nothing as yet. I just stay quiet. I am afraid to tell him that I am sent to

watch by Master Curtis….”

“John! Don’t you see that if you tell him that he will put you in prison or on trial?”

“Yes, and then how would I be with my Martha?”

“Exactly. Debbie, how are we going to help John? He’ll be killed next thing, and then we can do nothing for him!”

“Oh, don’t say killed Sirs, though then I might see my Mammy!”

“But not your Martha,” said Debbie. Even she was beginning to feel that the boy was a big baby.

“Lindy, why don’t we do some of John’s spying for him? Nobody can see us.”

“What a good idea. John, you keep out of sight of the Major’s house. Tell us where it is, and we shall go there ourselves.”

“Well, you know Paircy Mills?”

“Yes.”

“Do you know the BeeHive, where the post is picked up?”

“Yes.”

“Across from the BeeHive is an old bridge across the river, and just there is a house, not made of logs, mind, but of fine planed lumber, and that’s the Major’s house.”

“We’ll go there in your place.”

“But what if the Major catches you?”

“Silly, he can’t see us to catch us. Do you disbelieve the power of the Little People?”

“Oh, Sirs, begging your pardon, no, not that.”

John was repentant at once. Linda thought how she preferred him to treat them as equals, but it was tempting to pull the Little People argument to control him.

“Will you be going to the Major’s tonight?”

“Yes, John, we will. And now it is time to say goodbye, until we meet again.”

The fact was that Linda found John a strain, and wanted to be back in the comforting presence of the Topher. She seemed to have found the appropriate formula because John’s eyes grew round, and he had just time to say in a whisper,

“Wheels! the wheels of vision!” before the Little People faded from sight.

As he faded from the girls’ sight, the schoolhouse reappeared. The Topher was sitting on the doorstep, and shaking his head, opened his eyes, and looked towards them.

“That was great!” he said, “I saw and heard everything!”