The Topher

by Graham Cotter

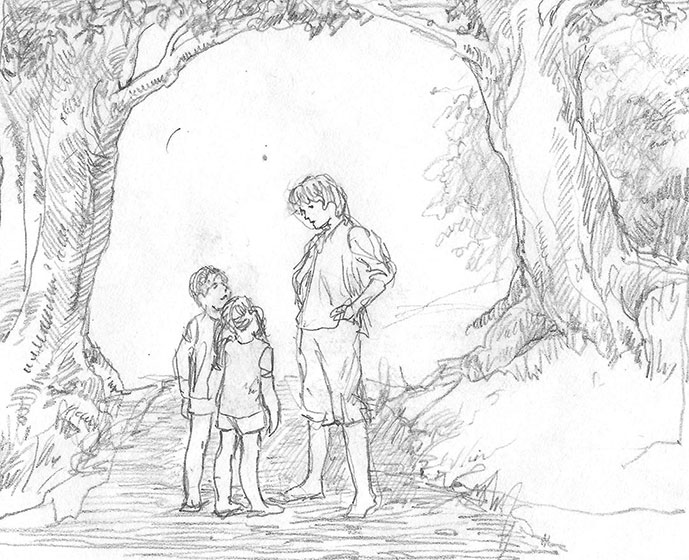

Two Times in One Place

Illustration by Audrey Caryi

The Topher grew accustomed to the girls’ disappearance, as he was growing accustomed to many unusual things. He continued along the road thinking that, by some extraordinary miracle in which he had a part to play, his two little friends had passed down the same road not just now, while he was slowly pedalling along, but about one hundred and thirty years ago. That would bring John’s time to about the time of William Lyon Mackenzie’s rebellion in Upper Canada. He could not be just sure, from the information he could remember, whether the events in Norham and Percy Mills were before or after the fateful winter of 1836.

There did not seem to have been a correspondence of time of year nor time of day. He had noticed as he looked through the eyes of John, lying down back there to spy on the militia, that the time of day was late afternoon, whereas his own time of day, and that from which the girls had just evaporated, was about noon. Also, he smelled something special through John’s senses: although the lilac in 1974 was that of August, with little green fruit instead of flowers, in John’s experience, it was heavy scented flowering season, May or early June at the latest.

He passed over the same bridge — no, not the same bridge, but the same bridging of the river — as the girls; but his bridge was a cement motor bridge, theirs of rough wood. He did not know this. Nor did he know, as he came to a larger grey brick house, with markings of removed verandah roofs on its sides, that the girls had been barked at by dogs from the wooden original of this former inn. He looked at it, thinking there was something familiar about it. What was it? He drew up under a tree and rested his bike, a frown above his eyes, trying to recall some elusive memory.

Then he realized that it was not his own memory, but John’s that he was penetrating. As he stood there, under the tree, head bowed as if in prayer, the present disappeared from view, and he was with John.

John was walking very carefully through the woods which lay between the scene of the militia drill and Percy Mills, where the girls’ route lay along the road, his lay along the hills to the south of the road and south of the winding river. The woods were heavy, mostly virgin forest, with occasional clearings as a settler’s lot touched upon his route. He knew the way well, but was going very cautiously for fear of discovery. As he went, he was thinking, not of the strange Little People who were so good to him, but of his Martha. Her face came vividly to his mind, and the Topher again saw her, but now as a grown girl. She had not grown very tall, but had black long hair and sharp brown eyes. The Topher wondered how someone so intelligent could put up with the superstitious, bumbling John. Then he recalled that he himself had a deep lifelong affection for the same bumbling John. It was strange. John was so different from him, and yet so much a part of him. What strange fate had brought their two minds into conjunction?

But John’s mind did not seem to include awareness of the Topher. Linda and Debbie were the link by which Topher’s world could impress itself on John. Why? At the same time these questions were going through his mind he was following John’s thoughts. John was simply terrified. He was simple and easily believed anything he was told, so his fear of the supernatural had gone when he discovered that the Little People were friendly and on his side. It was the natural world of human enemies which frightened him: both John and Comfort Curtis, with their fierce brows and hard vowels which seemed to bite into him when they talked; the Major and the Sergeant, their barbaric uniforms, their weapons of war and their strong Old Country accents.

But worst of all, he was afraid that the conflict in which he was forced to take part would keep him from his beloved Martha. He saw much more of her now, of course, since he was always at the Curtis house doing errands for her father and uncle. But he could see that it was so likely that, before he could achieve his purpose of marrying her, he would be shot down or bayoneted by the redcoats from Percy Mills. Or perhaps, just die of fright.

And Martha was so precious. She gave him nerve and supported him against his fears. She was a very good cook and looked after the family housekeeping, since her mother was dead, her uncle unmarried, and there was just a small brother beside herself. She was in fact, a young woman, while John was just a trembling boy. As John pushed gingerly through the forest, his face and hands tingled at the thought of her, of her warmth and of the softness of her hand when occasionally she touched him.

Illustration by Audrey Caryi

These sensations came through to the Topher as he stood aware of his surroundings, propping his bicycle under a tree. He too could see Martha’s warmth coming through in words he imagined her speaking and the softness of her touch.

Then everything changed. John was shaken out of his reverie about Martha as he came to a clearing. He was at the top of the hill, overlooking the river just where it winds out of Percy Mills and not far from the rise in the road which goes to Norham. He could hear in the distance, on the other side of the village, a roaring masculine voice — it was the Sergeant’s — and a commotion. There were also girlish voices raised in loud alarm and merriment, and he recognized the Little People. What could be happening? Could harm come to them? He ran along the edge of the hill, not caring for a moment that he might be seen, and hid behind a large tree on the Norham Road.

That commotion died down and John began to recollect his thoughts. Who

were these Little People, anyway? They might almost be human. In fact, hearing their voices from a distance they might be human boys or girls. He did not know what either boys or girls looked like with so few clothes on as the Little People had taken to wearing since his second meeting with them, so he did not know. He could not believe that they were ordinary — they must be sent from God. But still, he had seen enough of them to hear their voices and look closely at them without the awe of the first encounter.

They could appear or disappear, which he could not do. And they also rode those machines which reminded him of the vision of Ezekiel. He gave up trying to understand who they were, but he hoped and prayed that no harm could come to them. If, he thought, he prayed to God about the Little People, then he knew that God was greater than they. Perhaps they were angels — whatever angels were. But they seemed vulnerable, when he thought of them in absence. They were dear, warm, gentle folk, like his Martha, but he had no ambition to see them again, except… when they might come to his aid. But he cared for them, and was able to forget himself enough in thinking about them that he knew he could risk as much for them as he was already risking for Martha.

It was strange for the Topher to receive these thoughts from John, and also to have his own emotional response side by side with John’s. He knew who the “Little People” were, and knew they were in fact quite vulnerable and indeed might be in need of help — help which he could not give them, except through John, when they were in John’s time. This was a frustrating thought, for the Topher had never had control of John’s thoughts or action. But the Topher, while he knew the girls’ identity, was as much in the dark as John — perhaps more so.

John could attribute the Little People’s presence and actions to God and leave it at that; before the Topher there stretched the knowledge that a scientific impossibility, time-travel, was actually happening to his friends, and he was witnessing it. In addition, the Topher had his doubts about an agent called God. His practice of yoga, and the cast of mind of people his own age, made him think of such a Being as a remote force with which he could identify in moments of great peace not as a power who would interfere in people’s lives.

Yet the present events made it clear that some very powerful and wholly unknown force was interfering, against what he understood to be nature’s laws, in his life and the girls’, and doing so with a purpose. Moreover, there had been some interference in his own life as far back as he could remember: John.

At this point a strange thing happened to the Topher. He had carried on his reflections at the same time that he was wholly aware of the conscious mind of John; they came, for the first time since he had lived with Mary, with intense awareness of Martha. John was at that moment thinking of her and groaning that he might die before he married her. She represented the fulfillment of his desires. His feelings were passionate in a physical way, but also sentimental, and despondent; there was a great ache as he saw the distance between his incomplete self and herself, who could complete his life. The Topher’s feelings, his own feelings, not John’s, welled up in a similar way.

But he saw Martha, in her prim little workaday clothes and bonnet, going efficiently about the work of her father’s house, not as the fulfillment of his sexual need or his need to be loved. She suddenly became a person to be worshipped, a being for whom he would do anything he could, even give up his life. He experienced love as the desire to care for the beloved, not the desire to be loved himself.

The Topher could now understand why John left milk for the Little People and why primitive believers poured wine on the ground as an offering. He had the overwhelming desire to offer himself. Strange that Martha should be the object of that desire. Martha’s face and figure flashed from his mind, and he saw, through John’s eyes, the two girls finding, then pushing, their bikes up the hill to where John stood.

As John stepped out from the tree and spoke with them, something worried the Topher. The girls were talking about danger to John; he was preoccupied with danger to the girls. What could it be? Then, slowly, a sound from his own century bore in upon his consciousness, an automobile engine. Where? The girls were still in the middle of the rutted road, talking with John. Now through the image of the road he could see the later road, asphalt and meant for cars which could run on it many times faster than John’s best means of transportation.

It came to him: if the girls came back to this year at that spot right now, they might do so in the very path of a car and be killed.

He shouted, “Debbie, Linda! Get off the road!”