The Topher

by Graham Cotter

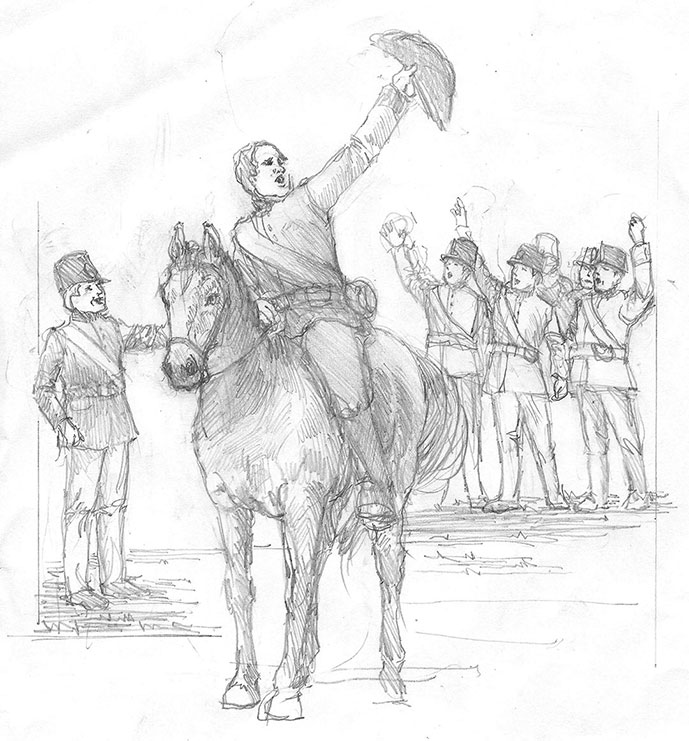

In Full Battle Dress

Illustration by Audrey Caryi

As Linda came to the top of the rise above Percy Mills, she was aware of a hush over the village, more than would be expected in the early evening in June. Where men, women and children would still be at their chores — for even the village homes each had a barn, at least one cow and numerous chickens, not to mention pigs — there was an unusual lack of activity. Very few people could be seen at all, and many of the doors of the houses that were visible as she came down the sloping road were apparently bolted.

There were, however, sounds of activity from the far end of the village, over by the river, where the Major’s home was located, and where she and Debbie had eavesdropped earlier and had their earlier adventure. She wheeled her bicycle as quickly as she could over the rough stones and ruts of the street. She knew she could not be seen, but her heart still beat fast as she approached, fearful of what she might find and worse, what she might have to do.

As the rounded top of the BeeHive came into view, she saw various men standing around in groups. Some were in the rough uniforms of the redcoats, but others were dressed much like the farmers at Norham. In the first group she came to one of the farmers, evidently prosperous, wearing breeches and a cravat of blue about his shirt collar. He was talking vigorously to two men in redcoat uniform.

“Now, James and Tulkie, I’m telling both of ye, this matter must be finished right quickly, and the rebels put down. I miss you both at your work; the back hundred is not yet ploughed, and who knows how long this fine ploughing weather will last?”

“Yes Sorr,” said James and Tulkie together.

“And when we’ve tamed that lot, we’ll put them to work on building that tollgate they object to, so you can get on with the profitable work of the land. Have ye experience at this fighting business?”

“I have, Master Kennedy,” said James, “I fought under Colonel Gore, sorr, last November at St. Denis, against the Quebec rebels, sorr.”

“And did you see action?”

“Sorr?”

“Were you firing a musket, man, and were you fired at?”

“Well, Master Kennedy, I was kept at the back of the shooting, to prepare powder and shot. And when it was over I helped the wounded, and there were many dead.”

James’s eyes were downcast as he spoke of the dead.

“Why did you so soon leave the militia and come to Upper Canada?”

“I heard there was work here, sorr, and I could never understand what the rebellion and the politics was all about.”

“But you know now?”

“Major Campbell has told us we are fighting for the King!”

“It is the Queen, now, God bless her! And you, Tulkie?”

“Yes sorr, Master Kennedy?”

“Are you a soldier?”

“I am now, sorr, sworn by Major Campbell, but you know I’ve never fought!”

“Never fought in a war, my lad, but often enough at the tavern! Are you ready to do your duty?”

“Yes, sorr, always, and whatever you say, Master Kennedy.”

Linda moved onto the next group of men. Here she recognized Major Campbell, and a heavy man, thick, with huge hands and knuckles, and great black brows that seemed to be longer than his bristly black hair. They were in some kind of argument, and some redcoat soldiers were standing near.

“Miller Stone, to defeat the rebels, you must accept some military discipline. I hold her Majesty’s commission. I am in charge of putting down this rebellion. You owe obedience to me while the emergency lasts.”

“Obedience, yaas,” roared the Miller, “but you cannot have flour from my mill for nothing in the name of obedience! Do you not fear God, Major, who says the labourer is worthy of his wages?”

“Now Giles Stone, Master Miller, there’s no need to bring God into this. You’ll have your pay when the matter is settled. If we wait for silver to arrive from York or Montreal, these rebels may have your mill burnt about your head!”

“Burnt about my head!” Giles Stone jumped up and down and shook his fists, “What in God’s name are you and the soldiers sent to protect us from?”

“Not me and the soldiers, Stone — you and me, and the rest, for you are in the Queen’s militia yourself. You’d know something of the art of war if you turned up to drill with the rest of these men, and you’d know that successful campaigning requires obedience to orders.”

“Burnt about my head” roared Stone again, “If my mill is to burn, I’ll take twelve rebels with me into hell with my mill.”

Major Campbell seemed accustomed to the miller’s raging. Turning on his heel, he called across to the remaining soldiers, who were standing in front of his quarters.

“Sergeant Cameron! Have the men fall in!”

“Yes, Major, Sorr!” called the Sergeant. “Northumberland Militia Company — in lines — fall in!”

The men moved at various paces to form two lines just west of the bridge. It was evident which the experienced soldiers were and which were raw militia, for the latter dawdled, the former ran. Master Kennedy and Miller Stone stood uncertainly about in the face of this military organization, the one’s experience being of cows and horses and farm help, the others of flour bags and grist, and of customers who were afraid of him.

The Major marched smartly to review his men. Then, before he said a word to his sergeant, he called to the two local Tories:

“Master Kennedy and Master Stone! I’ll thank ye to report to me right here, right now!”

Kennedy waked over confidently; Stone, his chest heaving and brows beetling, shuffled reluctantly, looking from side to side, trying to find reasons for opposition.

“Sergeant, parade the company!”

“Company, atten — shun!” The men came to some kind of attention, the odd soldiers standing perfectly still, their muskets, flintlocks and odd weapons, some with nasty looking bayonets attached, at their sides.

“Master Kennedy, under the authority vested in me by the Crown, and reposing especial trust and confidence in your loyalty, courage and good conduct, I appoint you Lieutenant in Her Majesty’s Northumberland Militia. Will you swear to be loyal to the Queen against all treasonous acts of rebellion?

“Yes, Major, Sir, I do swear.” Kennedy was beginning to enjoy this. Anything which had authority he enjoyed.

“Very well. Men, Lieutenant Kennedy is second in command of this company. Should I be killed or wounded, your obedience is to him in all lawful commands, and you are to obey his orders when deputized by me!”

Linda was duly impressed by this military rigmarole. How, she wondered, would the confused crowd of rebels, with their shouting and their fiery leader, stand against this discipline, and the awesome name of the Queen. She moved closer, still standing well to one side of any possible traffic or activity.

The Major then called on Giles Stone, Master Miller, to stand forward. Stone, still fuming at the thought of having to supply free flour to the soldiers, could not think of further objections. The military array was too much for him. He responded gruffly, but sufficiently, to the Major’s demand that he swear in, also as a lieutenant.

“Men,” said the Major, “Lieutenant Stone is Quartermaster of this company so long as the emergency shall last. In matters to do with supply and the provision of rations he is to be obeyed. Should Lieutenant Kennedy and I both be put out of action, he is to take command.”

At this Sergeant Cameron, standing stiffly to attention, winced; Kennedy he was sure he could handle, but this rough colonial clearly had no idea of discipline or warfare.

“Lieutenant Stone, your orders are to find for my troops adequate provisions of food, at once, so that we shall not begin in the morning hungry. You may demand from Her Majesty’s loyal subjects, such provisions as are needed, always giving them in writing a receipt for such goods. These expenses and your own will be met by the government at York, and full payment made.”

Stone looked up at this. That sounded like better sense. He was in charge of provisions, good! He would charge too. And when the rebels were put down he would take what provisions he wished from their houses, and especially from the tavern of his hated brother Jerimias. He looked forward to this. His brother had been a main opponent of his attempt to increase the price of milling flour, and had taken up with the farmers around Norham and down to Cramahe.

“Now, men,” continued the Major, ” we take what rest we can for the remainder of the night, eat rations early in the morning, and get an early march to Norham, to Stone’s Tavern in that place, before the rebels can assemble there at noon. Our outpost is already at Sugar Grove, home of the detested rebels, the brothers Curtis, and Sergeant Cameron has left his brother in charge, holding the young woman. I have other men deployed between here and there to see that no spies are walking “ (Linda laughed to herself) ” and if we take the houses of Norham one by one the rebels will fear to assemble, with their wives and children and neighbors in our hands. Such as are known to have urged insurrection against the government shall be arrested. We hope we shall not have to fire a shot; but be prepared, if they attack us, we shall have to engage them in battle.”

Linda sat down at the foot of the tree where she had parked her bicycle. Although in her time — 1974 time — it was only afternoon, and early at that, she felt the sleepy pull of the darkness of this earlier year and day, and dozed off. Around her, the soldiers made themselves comfortable, and Giles Stone, the Miller, taking two well-trained men with him, began to haul sacks of flour from the mill; he roused up the owners of the BeeHive for supplies and sent off two more parties of men to stir up the Inn on the road that went east, and the rough wooden Inn on the main street (in 1974 in Linda’s time the site of the Pine Ridge Inn, a late Victorian construction). The men would get their breakfast, and Stone would get his cut of the costs. Major Campbell and Lieutenant Kennedy retired to the Major’s quarters.

When Linda awoke, the faint light of early dawn was showing in the east. The soldiers were stirring, and she noticed that more seemed to be equipped with red jackets than before. Perhaps the Major had a store of these ready for just such an occasion. Sergeant Cameron was moving everywhere, outfitting new men who had arrived, and giving elementary training in use of arms to the inexperienced. Giles Stone had taken unto himself a number of men, both those he had sent to get provisions the previous night and any more he could find. There were pots boiling inside the Major’s residence, if clouds of steam and smoke were any evidence, and when Linda walked around past the bridge she could see more activity in the main street inn, and even hear shouts and commotion as far away as the Wayside Inn, near the site of the Percy Centennial School she attended in her own time.

Feeling a little hungry, she slipped into the Major’s house and found the kitchen. A fat woman in long skirts and a bonnet was preparing porridge. Linda’s problem was how to get some of this without the kitchen helpers seeing a spoon move itself into the air. Just how long in the process of digestion, she wondered, would the porridge remain visible? She giggled at the thought. But hunger proved this time to be the mother of invention. Finding a clean metal plate, she contrived to slip under the cook’s fat elbow, as she was dishing out porridge into bowls for the troops. Then she jogged the cook’s arm just as her ladle was above the plate and used her other hand to give the ladle a twist. A lump of gruel fell neatly on the plate!

The cook roared with anger, and reached around to hit the nearest person a whack with her ladle. This happened to be Lieutenant Giles Stone, quartermaster, who was inspecting the kitchen. The exchange of language that followed added to Linda’s knowledge of the existence of words in the English language, though she was not sure what they all meant. The cook, it appeared, was Giles Stone’s sister-in-law, English born, and with a low opinion of her sister’s choice in marriage.

In the confusion — in which all ladling stopped — Linda snatched the plate, making it swoop to the floor, and from there, unobserved, moved into a dark storeroom where she was able to eat a bit of it. First, it burned her fingers, then, after it cooled, she managed to get some in her mouth. It was a mixture of cooked oats, wheat and barley, none of the grains more than slightly broken in the milling process. Miller Stone was unloading his unsalable grain on the army and into it was mixed some sugar and water. It was like sweet glue with sand in it. Linda’s appetite soon faded, and, discarding the plate, she made her way out. She wiped off her hands on the back of Miller Stone’s new red jacket as she did so.

Time passed quickly for Linda as the preparations for leaving were made. The sun was well up in the sky and the day growing hot, as the militia formed up. Major Campbell had found a large farm horse to mount to make his inspection. He and the other two officers were splendid in red coats – Stone’s was too small for him – with brass buttons down the front, braided cuffs and collars, and epaulettes, round shoulder decorations, with tassels of gold hanging from them. Each carried a sword, and Campbell and Kennedy had a pistol as well. Stone, fortunately, did not have to do much parading, for he had neither the right figure nor disposition for parades and ritual. But as the Major rode up and down on his horse, Lieutenant Kennedy walked smartly at his side, his sword held in front of him, and a private soldier with his rifle at the slope upon his shoulder walked by his side.

“Major, do you think we’ll take them by surprise?”

“Yes, Mr. Kennedy, without a doubt. I expect no shooting.”

“How many of them will we hang when we take them? To teach the others a lesson?”

The Major was shocked.

“Lieutenant, remember, these are our fellow countrymen. We are to keep the peace and restore order, not to incite to rebellion!”

“Major, the rebellion is there already. These people are refusing to pay what is due to us. They are resisting the toll gate, and wanting more liberty from the King’s government at York!”

“Queen’s Government, Mr. Kennedy. And remember, the Queen’s Governor, the Earl of Durham, has recommended leniency with many rebels, saying that they have had provocation from the greed of those in the Legislative Assembly.”

“Gad, Major! these rebels are hardly fellow countrymen! Most of them or their fathers came from the American Colonies, a land of traitors!”

“But they came here from a loyalty to the Crown!”

“And they came bringing their notions of liberty with them! And Major, the few that do come from the old country, as I did, are a radical lot, not men of position like myself, a landowner, with a due respect for gentlemen!”

“I thought you came from Ireland, Mr. Kennedy.”

“Exactly. The old country, God save the King.”

The Major groaned. What with an Irish Lieutenant, a fierce Scots Sergeant, and an undisciplined Canadian Quartermaster, he wondered if any mercy would be shown on the Norham rebels.

In the meantime, the Sergeant had disposed his company as best he could. Some of his most reliable men, including his brother, were still acting as outposts all the way to Sugar Grove. But the remainder of the trained men, with the best uniforms and firearms, he placed at the head of the column. The company was now in the three lines, all facing, front, and the head of the column would be on the left, so as to march off in file when they all turned right.

Linda giggled at the sight of them. The soldiers wore bands across their chests to support the weight of the kits of ammunition at each side. Even the raw volunteers had been fitted up with them. Most of the jackets were red, but here and there appeared a blue one of military cut, belonging to some father or uncle of a new Canadian who had fought in the battles of Europe, or in the war against the Colonies twenty-five years ago. The professionals had white breeches, with spats covering the tops of their boots (Linda did not know they were called ‘spats’, but found out later).

Further down each line the volunteers had an array of garments: some had

waistcoats with side pockets under their jackets; one man wore striped pants with a double row of gentlemen’s brass buttons on his waistcoat, and two or three who appeared to be Indians, had moccasins on their feet, leather pants and tops, and a variety of knives, horns and hatchets hung around their chests.

But the great variety was in hats. The proper soldiers each had great blue hats which hung down like horns at each side and the Sergeant and his helpers – non-commissioned officers – sported a cockade of feathers to one side. The officers’ hats were much the same design, like a half moon, but they wore them so that the stiffened ends, like the front and back of paper boats turned upside down, were front to back. The Major’s came so low he must be cross-eyed, she thought. Mr. Kennedy had pushed his back a bit from his forehead, so that the great cockade stuck back like the plumage on some strange bird, or the queer long skull of the old beasts she had seen when she visited the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto.

Miller Stone had fought with his hat, and it was askew, neither from side to side like a soldier, nor front to back like an officer, but diagonal, like his personality. The other hats included several which were certainly military, such as a great fur box with a cockade in the middle. But most the volunteers had all kinds of civilian hats: broad brims and narrow brims, hats with bands and squashed hats, caps and peaks, and for the ‘Indians’, skin hats with the animal’s tail hanging down one side ( Linda had seen Davey Crockett re-runs on the TV which made these familiar).

“Men,” said the Major, “You are now all under military command, and must obey your superiors. A man disobeying may be shot without trial on the field of battle. We are to march in silence until we reach Sugar Grove, then the drummer will strike up. I do not expect resistance to a fine” – the Major swallowed as though something had stuck in his throat, – “group of loyal militia such as yourselves. We are to make a show to put down all thoughts of rebellion, only if absolutely necessary to engage in fire. Military discipline demands obedience in refraining from harmful acts as much as in carrying out orders to engage the enemy.” (Linda noticed angry looks from the Sergeant.) “Now, prepare to march, and God save the Queen!”

He raised his hat in the air, Kennedy brandished his sword, and the whole company responded, “God save the Queen!” After a sharp order from the Sergeant, the troops turned right, the Major rode ahead, and the march began, Linda cycling at the rear.