The Topher

by Graham Cotter

Stone’s Tavern

Illustration by Audrey Caryi

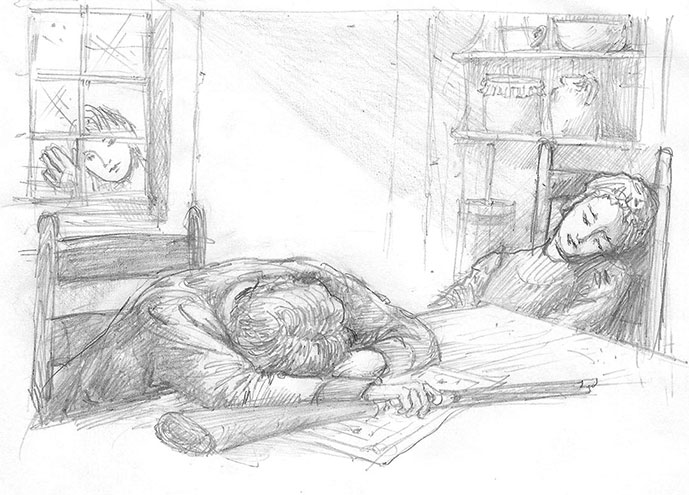

Debbie’s night had passed much less eventfully for her, for she fell asleep with the approach of night, only a few hundred yards from the place where, years later in 1974, but somehow linked through dreams, the Topher slept away the afternoon at Mrs. MacAndrew’s. The deep sleep into which he had fallen after earlier restlessness was disturbed as he saw the figure of John, creeping away from the tavern where Jerimias Stone, the opposite in temperament and attitude to his brother Giles, had been handing out whisky to the rebel forces as they gathered.

The men had rowdily taken their fill, and then relapsed into sleep themselves. But not John. He was waiting for his chance to rescue Martha. Waiting till the last sound of wakefulness had disappeared, at about three in the morning, he crept off from the tavern, passing the sleeping guards who had been posted on the road to Sugar Grove, by stealing through the fields alone.

Sugar Grove itself lay as a darker mass amid the darkness at the top of the hill. John approached, half crawling and half stooping, determined not to make a sound. Finally, he was in the midst of trees south of the driveway, and could see the picket fence. A dim light burned in the window, from the oil lamp the younger Cameron had left to keep an eye on his captive. John tried to see past the light into the room. The Topher, clenching his fists in his sleep, willed his way into seeing the room. It was as though he stole like a spirit through the lighted window, and saw there Cameron, large and ruddy like his brother the Sergeant, sprawled across the table, one hand on his musket, which was pointed directly at Martha.

She was dozing in her chair, still holding in her hands the white and red cloth she had been sewing. The Topher tried to bore into her brain, saying out loud in his sleep (just as Mrs. MacAndrew looked in), still

“Martha, Martha, this is John, I am just outside the house. Martha! this is John!”

Martha opened her eyes slowly, and looked about her. She was still gagged, having been fed and then gagged again, but still had not been tied. She had been so pliable with the soldiers that she did not seem likely to do anything rash. Looking over at the soldier and then at the low flickering light, she reached over, tapped his arm, and said, mumbling through her gag,

“Shirr, shirr.”

Cameron woke with a start, grabbing his gun.

“Tshide, tshide,”mumbled Martha, pointing with her hand. Cameron leaped up, unbolted the door and went out, rushing to the side of the house nearest Norham. He could see nothing, but at that moment, John, for the first time in his silent approach, snapped a twig among the bushes. The soldier shot his gun in the direction of the noise and began to advance, trying to reload as he did so.

He did not notice that behind him the light was blown out, and Martha

slipped out the door, still clutching her sewing. She raced across to the shelter of the maple trees, but away from Cameron’s line of advance and then, having snatched the gag, called in her best rooster voice,

“Cocka-doodle dooo!”

Cameron raced towards this new sound, but almost at once, the dumb chickens, awakened by a familiar call began their crowing first from the rear of the house and then, picking up the call, from Percy Mills and from the nearer chicken coops in Norham. The soldier, still unaware that his captive had escaped, ran around to the back of the house, and discharged his gun again.

John, who had seen Martha rush out, went over to where she was hiding, and gave her a great hug.

“My Martha!” he said, “you’re safe!”

“But you’re not, foolish boy, you’ll be dead if he returns,” and she dragged John down the road which ran west on the edge of the Curtis land.

If there had not been a commotion at the farmhouse, they would have come close to the next outpost, but he, hearing the noise, ran across the field at the back of the house, where Cameron had fallen into the chicken run. Cameron was trying to get feathers out of his mouth after being attacked by a real rooster, who had flown down from his roost to protect his squawking hens. John and Martha made their way through fields back to Norham, and the Topher rolling over, went into a deep, undreaming sleep.

The uproar at Sugar Grove had wakened the rebel guards, who now stood ready to take on the militia. It was with some difficulty that John and Martha approached without being shot at, but they came along slowly, stopping frequently to kiss and hug, never having been together before at such a tempting hour of the night, nor after such warming adventures.

Debbie also wakened, and, slipping unseen through the outposts, came upon the two when they were swaying together rapturously under a tree. This being what Debbie had wished to see all along she stood in silence, eagerly watching the love-making, until John disengaged one hand to scratch his head! At this Debbie burst out laughing, and John, alone hearing her, started back and looked around him. Debbie ducked low.

“Martha, dear, I truly love you, but we must find your father and tell him you are free, and not keep the good man brooding for your safety.”

“Yes John, and not let him know we’ve been too long coming to Norham!”

So the two moved off quietly through the night, followed by John’s guardian Little Person.

John Curtis, when they found him, was indeed brooding, sitting up with a great scowl on his face in the upper room at the Inn. His brother Comfort, for once, was quiet beside him, sound asleep.

“Ah, there you are my precious daughter!” He rose and embraced Martha. “And have those Tories hurt thee?”

“Not at all father! And John here came and set me free, at great peril to himself.”

Debbie grinned to herself as she witnessed this. John had certainly intended to set Martha free, but had not done it without her cooperation — Debbie had overheard Martha telling how she had heard John’s voice in her dreams and deceived Cameron.

“Master Quakenbush, you’re a man, and a man among men!”

John Curtis held out his hand and gripped John’s. The boy met the older man’s eye and looked as stern as he could, to put himself on a level with Curtis’ perpetual scowl.

“Master Curtis, I wish when this is over, to marry your daughter!”

Master Curtis sighed.

“I never thought ye’d be worthy of her, but ye’ve proved yerself. We’ll take you into the family indeed!”

“Ho! What’s going on? What’s the noise out there?”

Comfort Curtis rose from his dreams, his eyes still blazing with their usual

light.

“Brother, this young man of yours” – John Curtis regarded the young Quackenbush as a special discovery of his wild brother’s – “has rescued Martha, and set the Tories firing and the cocks crowing!”

“They’re not marching?”

“Doubt that. Not so early.”

“Not too early to get our men ready. Jerimias can put some gruel in them where he filled us with his drink last night.”

“Gruel, yes, better than what he handed out last night.”

So it was that, perhaps somewhat earlier than Linda, Debbie also tasted the heavy porridge with which people then gave themselves a booster for the day. But Jerimias’ porridge was the best, mixed with good sugar, and when John slipped a little helping to Debbie — without now questioning why the Little People should need food at all — she quite enjoyed a few spoonfuls. And Jerimias emptied all his

supplies of chocolate to produce a strong black drink to warm up the rebels after their uncomfortable boozy sleep.

Martha was carefully put to bed by Mrs. Jerimias Stone, to recover from her captivity, and young John shooed away from her door more than once. He was sent out to take his place amongst the rebel ranks. Some of the rebels had served as Loyalist militia themselves in the War of 1812. Others were more recently American, having come across the border at Niagara or Cornwall to find free land and avoid wars with the Indians. Though most had fathers and mothers who had escaped from the rebel states in the American Revolution, few were military in

disposition.

There were also few firearms, but many unpleasant looking farm weapons. Debbie had often seen a hay fork, but never thought much about it as a weapon. Imagine one of those things stuck through you! Her stomach tightened at the thought, and a familiar shudder went through her as she realized that she might see several people with hay forks, and worse, sticking through them before the battle was over. Now she realized that this was not the game she and Linda had pretended to their mother that it was.

Their mother, at home on Scace’s hill, was wondering how the girls were. She did not call them but turned on the receiver to see if they were talking through the radio. At this moment Debbie’s signal rang, which only Debbie and John could hear.

“Hello, that you Lindy?”

“Debbie, the redcoats are marching towards Sugar Grove and Norham. I am following them.”

“Oh Lindy, John rescued Martha and she escaped!”

“Good! But you must tell John to get the rebels ready. There are twenty-five or thirty redcoats, following the Major, and some more men are riding in on horses to join the end of the march just now.”

“Okay, I’ll tell John. Nancy and Out.”

“Bye.”

The radio formula seemed a little silly to Linda by now, when things were getting serious. Her mother, listening to this brief exchange, was amazed at the realism of the game. It seemed to be at a crucial stage, and she supposed the children had had something to eat. It was about mid-afternoon for her, not midmorning for them. But she did not know that, nor that they had been eating nineteenth century porridge to keep up their strength.

Debbie, who had had the message as she sat by her bike under a tree some distance from the tavern to keep out of the way, rushed over to John, where he was being shown how to work one of the few muskets available. It was, in fact, his own father’s gun, and his father had been persuaded by Comfort’s messengers that his son was something of a hero and should be armed. But old Quackenbush himself had not come to join the rebels, being something of a recluse since his widowhood,

except for late night drinking. He thought he would let John carry politics for the family.

“John!”

She tugged at his sleeve.

He saw her, and handed back the weapon to Ellenbeck, who was instructing him.

“Master Emmanuel, I think I understand its working, I will take the musket again in a moment. I must attend to my boot, there’s a stone or perhaps a wasp in it, giving me the most terrible pain!”

Ellenbeck took the weapon and shook his head, wondering why John should suddenly have felt this thing in his boot, but turned away to see what else he could do. John squatted to undo his shoe, and Debbie spoke in his ear.

“The redcoats are marching John, they’re on their way to Sugar Grove and here. You must warn Master Comfort! And there are perhaps thirty or more of them!”

John, forgetting that his one boot was now off, jumped up and ran to

Comfort Curtis.

“Master Comfort! sir, I have a word for you. The Major has about forty men, and they have begun their march against us.”

“How have you word, young John?”

“I see it, Master Curtis, I see it, as I have rightly seen before!”

“I believe you,” said Curtis, not quite knowing why he should believe him, except that it was time anyway to form the men up in readiness for the assault. He set about his work of organizing the men to meet and defeat the Northumberland Militia.

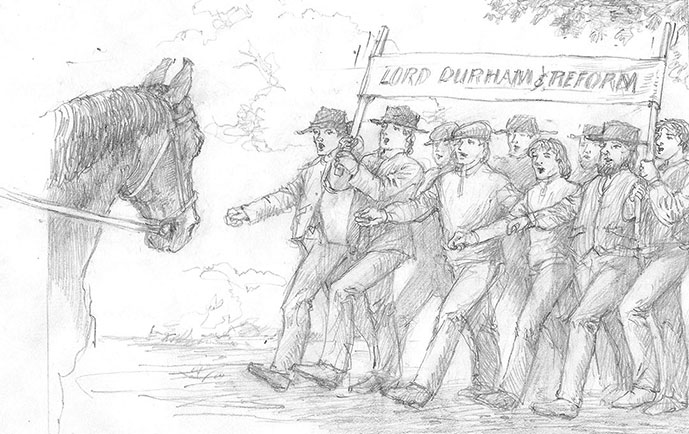

And so it was that some half an hour later, as Major Campbell’s forward scouts crept down the road from Sugar Bush, an imposing array met their eyes. There was little attempt at uniform and outward discipline among the embattled farmers of Norham, whose dress was more frequently like that of the fur-capped Indians amongst the militia.

But in numbers and fierceness they were most impressive. A line of men stood with hand weapons — hay forks, hoes, shovels, hammers, bars of iron, in a long line from the east end of Stone’s Tavern across the road and in front of the little chapel building. In front of them, some kneeling, some lying down, were the armed men, their great assortment of guns, and in some cases pieces made to look like guns, but equipped with bayonets to be of some use, pointing up the road towards Sugar Grove.

What the scouts could not see was that in addition to these men, who

numbered at least forty-five, there were small groups of ten or so each. In the fields or behind the houses on the Sugar Grove Road, each party had at least two firearms among them, as well as hand weapons and farm implements, and lay in ambush to rush the soldiers when they moved down the road. The militia might be superior in arms and training, but they were outnumbered and would be in serious trouble.

But the most impressive sight for the scouts was not the many fighters and their disposition. It was the great banner across the road, from the upper windows of the Tavern to a pole set on the roof of the Chapel, which spelled

“LORD DURHAM AND REFORM.”

Illustration by Audrey Caryi