The Topher

by Graham Cotter

Norham

Illustration by Audrey Caryi

“And the girls were off having a Mad Hatter’s tea party in the woods.”

Thelma was recounting the events of the day to her husband at supper. Albert listened attentively as he cut the roast.

“And who was the Mad Hatter?” he asked.

“Oh, that was just a joke of Debbie’s,” replied his wife.

“Mum,” Linda reluctantly interrupted.

“What is it?”

“There was a Mad Hatter. Only he wasn’t mad or a hatter. That was Debbie’s joke.”

“Oh, who were you with?”

Thelma was mildly interested.

“A man who is camping in the woods.”

“He’s not a man, Mum, he’s a boy, and he’s gorgeous. We had tea with

him!”

“Well, which is he, a man or a boy?” asked Albert.

“He’s young, but I think he’s over nineteen,” replied Linda thoughtfully.

“Where’s he camping?”

“Down at the fork of the river beyond the hidden field.”

“Isn’t there quicksand down there? You need to be careful.”

“No, not much marsh even. Anyway, if it is there it’s dried up….”

“Tell me more about this boy,” said Thelma.

“He stands on his head and makes it empty and he has beautiful eyes.” Debbie was grinning at the memory.

“Sounds as though you’ve fallen for him, Debbie.” Her father gently

teased his little one.

“Hook, line and sinker,” put in her mother.

“Look, shine and thinker, only she hasn’t much of a thinker,” put in

Linda, not pleased that she hadn’t had a chance to answer the question.

She went on.

“He’s pretty interesting, and he wants to come to see you tomorrow, Mum.”

“Which of you girls does he want to marry?”

“Oh Daddy! It’s not like that at all–”

Linda kicked at Albert playfully under the table.

“Better not let him come here when you’re away, Albert. He seems to

have a way with women, and I’m very susceptible!”

Linda got up in a fury from the table.

“You can’t take anything I say seriously,” she sobbed. “He’s a nice friend, and all you can think of is SEX!”

She stormed off, her plate unfinished.

Thelma saw that she and her husband had carried their teasing too far and she went off after Linda to smooth things over. It was then that she discovered that the Topher — and what a funny name she thought it was! — would be coming about lunch time.

“Probably needs a square meal,” she thought to herself. “Mayapples and roots and mint tea!”

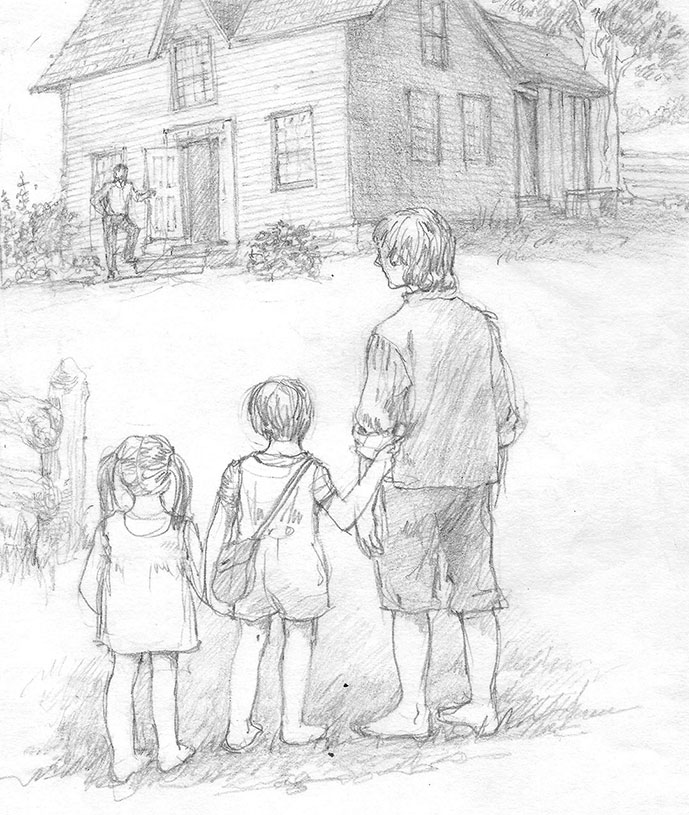

And so the Topher arrived the next day. The girls were excited about his coming all morning, and they were exceptionally helpful to their mother, tidying up the house to a degree she seldom achieved. She began to wonder if she was going to entertain a hippie youth camping in a swamp, or the Inspector General.

When at last she saw him, walking with a bounce up the drive, she realized why her girls were so excited. He was clearly an adult, yet he had an air of boyish interest and amusement about him, and enjoyed living life at his own pace, something many adults had forgotten how to do. She noticed too, during the introductory conversation, that there was a maturity which many adults never achieved, adults for whom life had apparently no pain and suffering.

He went patiently with the girls as they showed him all their treasures. A special expedition before lunch was to the toy village, a little collection of houses, people, and animals that was established every spring beside a little pool down the hillside. From there the girls were able to point out in the distance the large glacial rock near which they had had their adventure that summer.

“I thought you said you went to sleep among some trees?” he said.

“Yes, but after the explosion and the flood the trees and bushes were cleared. It looks very bare now. My brother Brian was furious. He loves closed-in places — places like your camp down by the river.”

“Well, if he comes home after I’m gone, be sure to show it to him.”

“Are you going, Toph?” asked Debbie adoringly, pulling at his hand.

“Well, sooner or later. My holiday doesn’t last forever.”

They tramped on back to the house, where Thelma had lunch ready for them. The Topher did seem glad to be having a sit-down meal, or at least, so it seemed to his hostess.

“The girls are terribly excited about having you as their friend,” said Thelma, trying not to sound like a prying mother, “but they haven’t said much about where you come from or what you do.”

“Well, I come from Toronto, and I live.”

The answer was just a little smart, and Debbie picked it up.

“We all do that, silly, she means do you work?”

“Yes, I’m trained as a librarian. I work at the Robarts Library….”

“Oh, the monster,” said Thelma. “It’s very threatening from the outside. But it’s a good library and I enjoy it there.”

“Have you been to Warkworth before?”

“No, and I’ve only just arrived. In fact, I’ve not been in the village yet at all. I came up and found a campsite and then the girls found me.”

“Standing on his head,” said Debbie.

“And they gave me a great scare, when that two-way radio suddenly beeped.”

The girls giggled. Their mother smiled.

“Have they told you why we use it?”

“Yes. I wonder why mothers and their children don’t use these things more. They are quite common as toys. And a good idea.”

“Well, this set is a lot better than the toy kind. And I feel better about them.”

The Topher ate in silence for a moment. Then he asked,

“Mrs. Scace, is Norham far from here?”

“Oh no, it’s actually closer than Warkworth. As the crow flies.”

“But not as the motor car drives,” said Linda, feeling it was time she asserted ownership of a part of the conversation. After all, they had discovered the Topher, not Mother.

“Do you know someone in Norham?”

“Yes – well, not exactly. But I especially want to visit it. Maybe with someone who knows it well.”

“We know it well, don’t we Lindy? You could come with us.”

“I don’t have a bike. It’s sort of hot to run beside you.”

“You could ride mine,” said Thelma. “If you don’t mind riding a woman’s.”

“Thanks very much. No, I don’t mind. The difference is silly nowadays, when very few girls wear skirts on a bike.”

“Tradition, I suppose,” said Thelma, on her favourite subject. “Keeping women in their place.”

But the Topher did not know her views, and lost the irony of her remark. He looked puzzled.

“Go ahead with it anytime you like. The girls will show you where it is, and it is in good shape.”

“Thanks a lot. Let me help you with the dishes first.”

“Okay. Just to clear. Then off you go. There’s quite a lot to Norham, although it’s so much smaller than Warkworth. You’ll be pretty hot and tired when you get back up that long hill, so don’t forget to stop in and have a beer. My husband may be back by then, too.”

Thelma looked after them as they rode down the drive together. He was certainly a handsome young man her girls had found. Safe, too. Many Mothers would have suspected him, with his long hair and his solitary camp, but the reason Thelma trusted him was that he clearly respected the girls — and herself. It was not a kind of false respect just because she was an adult; he really seemed to respect her as a person, and he seemed genuinely to like people of the opposite sex, without that bravado that some boys and men seemed to need when talking with women and girls.

There was something else about him. She could not define it clearly. He seemed to belong to the countryside, in a way she never would. In that respect he was like her husband, who had been born here and whose father had been born here. There was a reality to the bond between the boy and the countryside that was not logical. He was from the city and did not mention any connection, even with the township. Funny.

So it was that the three figures set off down the country road together. Just at the entrance to Warkworth they turned south, along the bypass to Morganston and up a long hill. Then they took a township road at the bottom of the same small hill, and soon they were among the scattered houses of little Norham.

As you come into Norham, from almost any direction, you wonder where the houses are. There is a main street, of sorts, and side streets, roughly parallel to each other. But very few houses. There is a supermarket, and the remains of a church building, now an antique store. And there are a few houses with ample yards, gardens and in some gardens — weeds.

The two girls and the Topher rode in on a gravel road and came to the asphalt road.

“Let’s go this way and see the dam,” said Linda. So they veered off, first right, and then left. The gravel road they were now on was well shaded by overhanging willows, and to one side there was marsh, where marsh marigolds bloom every spring.

“See, there’s the dam,” said Debbie.

The remains of the mill was there too, and what had been a pond was behind the dam. It was now mostly swamp, and curled off into the distance.

“Pretty spot,” said the Topher.

“But dangerous,” said Linda. “We’re not supposed to go off this road one little bit.”

“Okay, I can see that. Where next?”

“This way,” said Linda.

They rode a little further, sweeping round to the left and were back on the main road of the village. They stopped at the supermarket. It looked very well stocked for such a small place. It provided an alternative to the shops in Warkworth, and was very well patronized by the prosperous farmers around.

“Let’s show him the egg place,” said Linda.

“I want to go the haunted wood,” said Debbie.

“What’s the egg place?” said the Topher.

“A poultry farm. But you walk in and take the eggs you need and leave the money. People from the city think it’s marvelous the eggs don’t get stolen.”

“I’ll see it another time. Let’s go on to Debbie’s haunted wood.”

“Oh, Debbie, you just say it’s haunted. You’ve never seen anything

there…” Linda was sharp.

“Anyway, Lindy, it’s nice and cool in there on a day like this.”

So they rode up the hill but instead of continuing sharp left to the main road to Warkworth, they went on up a gravel road. At the top there was a barn on the right, quite old but in decent repair and on the left side there were tall trees clustered together, some of them fallen down.

“It doesn’t look like a real woodlot,” said the Topher.

“I think there used to be a house here,” said Linda. “See, there are flowers

like a garden over there, and here’s the remains of a road going that way.”

They left their bikes at the side of the road and went in to enjoy the cool air. Some of the big trees had fallen, and there was a matted growth to one side. Then there was a depression, like the outline of a house foundation.

“Gee, isn’t it lovely,” said Debbie, taking Topher’s arm. “You wouldn’t think the rest of the world existed.”

Linda gave her sister a hard look; she was getting altogether too familiar with this man. Then Linda stumbled, not looking where she was going. She fell flat, but did not hurt herself, and sat up quickly.

Once again, the magic change had worked upon them — or upon their

surroundings. She was sitting up on the lawn of a handsome one-and-a-half storey brick house. There was a neat iron fence around the lawn, and behind the house some of the same trees that a moment ago had seemed neglected and forlorn. Her sister and the boy were still beside her, but her attention was directed at a tall fierce figure coming out of the door. He had a long black beard, almost forking in two at the bottom, and his brows seemed permanently in a scowl.

“John boy! Have ye come to see Martha?” the man called out.

Linda then realized that he was calling to the Topher, who was near her. She looked around. Her sister was still there, her hands on the boy’s elbow. But the Topher was quite changed. He was a red-haired lad of about the same age, wearing wholly different clothes. Instead of the jeans and shirt he had a moment ago, there were britches, some bare calf and a kind of moccasin. He was wearing a long-sleeved white shirt, quite different from any style Linda had ever seen.

Debbie drew in her breath.

“Debbie, don’t scream!” Linda rushed over and held her sister. “The man can’t see us! It’s important! Keep quiet!”

Debbie subsided, and the tears began to roll down her shocked face.

“Yes, Mr. Curtis,” the boy called John replied, blushing. Then he looked straight at Linda, and said, “I can see you too. Please don’t go away this time.” His voice was not unlike the Topher’s in timbre, but his accent and speech were quite different, like something harsh and historical.

“Well, you can see her later. Right now there’s a meeting on, and if you want to pay court to my daughter, you better come to it and do what you’re told.” His speech was even harsher, his “r’s” stronger even than the Southern Ontario “r’s” the girls knew, and something was strange about the vowel sounds: “Later” and “meeting” and “daughter” seemed to have much the same sound.

“Yes, Mr. Curtis, just as you say.”

John gave a final wink in the direction of the girls, and walked up to the door. He and Mr. Curtis disappeared inside.

“Lindy, what can it be?” whispered Debbie, still choking back her sobs of fright. Linda had brightened up considerably; whatever it was this game with time was interesting, because there was someone “back there” who corresponded to their friend the Topher and who knew them. It wasn’t so lonely, knowing there was some person here who could see you and talk to you. It gave you a bearing, a starting-point.

“Debbie, you remember how you were upset when the Topher said that we

were the ghosts of Drumlin Hill, and the horse knew we were there?”

“Yes.”

“Well, you wanted to come to the haunted wood.”

“Yes,” said Debbie, trembling.

“But now we are here, we are here, we are haunting it, we are the ghosts, and that boy can see us and know us.”

“But I don’t wanna be a ghost!”

“You aren’t really. There’s always this –” pointing to the two-way radio she was carrying — “to keep in touch with Mum.”

“But — is that boy John — is he the Topher?”

“I don’t know. He seems a bit like him. Let’s follow and see where he’s gone.”

“Lindy, I’m scared.”

“You needn’t be. Only John can see us. You may never again get a chance to be invisible.”

“Gee, I’m invisible!”

This cast a more exciting light on their situation for Debbie. “I’m the invisible man!”

“Girl. And I’m another one,” said Linda cheerfully.

But now they had reached the door, and they carefully walked in. The big room they entered was apparently for both eating and leisure. Near the door was an old fashioned stove, though it was clearly not new, all its brass trimmings sparkling and carefully cleaned. It was not lit, and the steaming kettle on the table around which the men sat must have been brought in through a door in the summer kitchen Linda could just see at the back of the house.

There was a mat in loud colours on the floor, apparently made of dyed

rushes in a pattern of Indian beading. On the wall was a rough rack with two guns resting on it, some wooden pegs with clothes hung on them and a fancy home-made sign “For God and Country.”

There were seven men around the table, and the boy John was standing to one side. He winked as the girls came in; otherwise there was no sign that anyone knew they were present. The big scowling man who had been at the door was speaking.

“Now, brother Comfort, tell the boy what he’s wanted for!”

Brother Comfort was at one end of the table, and was clearly a leader. Tall as his brother John, he was much thinner, and wore no whiskers. His face was small and pointed, under very young-looking brown hair, and he spoke, not with John Curtis’ boom, but with a sharpness, hissing as he sucked in his breath between phrases, his dark little eyes bobbing around at the people about him.

“Boy!”

“Yessir!”

“You know that certain men of this Township have agreed with the fake noblemen of York to put limits on our trade in these parts.”

“Nossir!”

Young John was clearly astonished and not aware of what the fiery man was talking about. Comfort Curtis, however, paid no attention to his ignorance.

“And you know that young men such as yourself are likely to be picked

up and made to serve in the militia, whether they like it or not?”

“Nossir!”

“Well, you are now. Would you like to be made to leave home, and walk long marches, and have yer toes frozen in winter, and wear thick red wool in summer, and be shot if you don’t do what yer told?”

Comfort was getting into political stride, and talked to the boy as though he were on the next farm.

“Nossir, I would not, sir!”

“Faith, he would not,” came from a red-faced, yellow-haired man at the table. “He’d rather bed down with young Martha!”

The girls heard a giggle from the summer kitchen, and young John blushed. Debbie, who had stood loose-jawed and pop-eyed, began to understand the conversation, and Linda was mildly shocked, since that was what she believed she should be. But the fiery man went on.

“Yes! You’d rather be in comfort, and take my niece to wife, and live out yer days as a free man. But if Sirs, Lords and Squires at York –”

“Saving Lord Durham,” interjected one of the company.

“He’s not at York,” said Comfort.

“But he is a Lord,” replied the man weakly.

“– if those privileged oppressors have their way, you’ll have none of these things, and we’ll all live to touch our caps to a fine man in his carriage, and our wives curtsey to the made-up ladies with their fair skin. Boy!”

John jumped.

“Boy, you must fight for your freedom, and you must fight with us!”

“Yessir!”

“Comfort Curtis, you’d make a preacher! But tell me man, what’s worse now than was bad in December, when we had the troubles at York and all over?”

“I’m not concerned with York’s troubles; I’m concerned with those of our township who want to give us troubles of our own. I’m concerned ” (he pronounced it “kon-sayernd) “about Kennedy, who wants to put a toll on this very road, which our father and John and me built with our very hands; I’m concerned about Giles Stone, who’s charging twice what he did last year to grind at the mill. I’m concerned that there’s no free school in this township, but our money through those English gentry is going to that sissy school in Hastings, or down to Cobourg to the damn Bishop’s foundation!”

“But Comfort, man, I’ll agree with all that but I’ll also agree with Emmanuel Ellerbeck. What can we do about it?”

“I did not ask that question, Barnabas Brunson,” said the man called Emmanuel Ellerbeck.

“For I’ve proposals of my own in that matter. We must use the saw mill here for grist as well; we must refuse a toll on that road — ”

“Or make it a toll only for Stone and Kennedy!” said Brunson, laughing.

“And John Merriam, and Andrew Boyce.”

This from a quiet man at one side, who had nodded steadily at each point made by Comfort Curtis.

“That’s not enough!” Comfort was on his feet, his fists raised in the air.

“These lordly people will oppress us again and again unless we have good government. We must have the freedom to manage our own affairs in Upper Canada, as well as in Percy Township! We must have the reforms of Lord Durham!”

“But how will ye go about it, Comfort, man?”

“First, we must have no compulsory militia. In fact, we must drive that man Campbell and his Scots villains out of the Township, right out!”

“Not all Scots are villains!” shouted a black-haired, craggy man, getting to his feet.

“Of course not Robert Graham, of course not,” soothed John Curtis, intervening.

“But the best of them come through Ireland, eh, Robert, man!”

“Men, be serious and attend,” said Comfort. “We shall put our objections to the toll, and our objections to the cost of the mill, first to the county authorities at Cobourg. If there is no action, then we shall fight.”

“Agreed. Agreed.”

“Now, you boy, John, we need you as a messenger, a runner to keep us informed. It’s best you move in here with us now.”

“But–”

“I’ve spoken with your father. Yer taken on as a hired hand, and he’s happy. But no one is to know yer a runner for us, nor what you have heard today.”

(Again the girls noticed he said “he-yard.”)

“Yessir.”

“And mind yerself with my daughter!” roared John Curtis. “But you can have a polite word with her now.”

“Thank you sir!”

So the boy John walked to the summer kitchen, making a hidden signal to the girls to follow him. They tiptoed out, still believing they could not be seen. As they stepped over the threshold of the door, the summer kitchen, the house, and the garden all vanished, and they were back among the old maple trees, and the Topher was standing twenty feet away, staring at them.