The Topher

by Graham Cotter

The Hidden Field

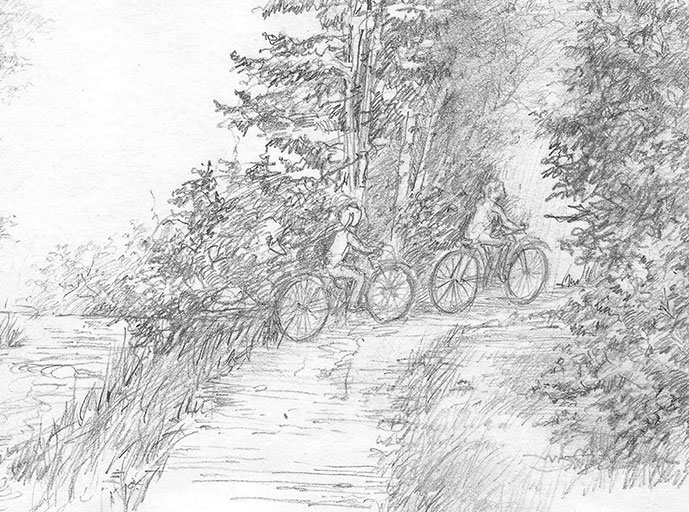

Illustration by Audrey Caryi

The girls finally had to walk their bikes the last quarter mile up Scace’s Hill before they reached home, and it was only then they began to talk about their experience.

“Oh-h-h, I’m so frightened,” said Debbie, “I want my Mummy!”

Linda reflected for a moment, then said,

“Debbie, I don’t think we’d better tell Mum about this.”

“Why not?”

“Cause either she’ll tell us we’re making up stories, or she’ll say we can’t go for rides like that away from home after all.”

“But we have the walkie-talkie!”

“Yes, and it was useful when we were scared. But it’s not as though anyone hurt us, or there was anyone who could hurt someone else.”

“Then who was that man? And what was wrong with Drumlin Hill?”

“I don’t know. But, it was like our dream when they thought we were lost. Maybe it didn’t happen, really.”

“I got scared Lindy. I know that. That hydro pole just jumped out of nowhere. And the horse was scary.”

“Maybe we shouldn’t tell Mummy anyway. Perhaps when Kevin comes home we could tell him. He had a sort of dream that time too.”

“Dirty old Kevin. He’d laugh at us worse than anyone.”

“Anyway, don’t tell Mum. It’d make her worry.”

By now they were nearly at the house. The drive swept right around the house, along the edge of Scace’s Hill from which you could see far over the Trent River. The house itself had great old trees rising above it, and was well shaded in the hottest weather. Originally, there was a small house, eighteen by twenty-five feet, with walls of mud, two feet thick. That was about the year 1804. Then the old house had been made into the kitchen, and in 1840 a small brick house had been built on one end, two stories high, but compact. On the other side of the kitchen what had originally been a stable was now both a work and utility room and a garage. Around this house an imaginative Victorian had built a verandah, with gingerbread scrollwork at the tops of the posts, and a slight flaring roof as it came to the eaves. Some distance away, over the edge of the hill, was a large barn.

“There you are girls,” called their Mother from the kitchen door.

“You’re home sooner than I thought.”

“Mummy, we rode so hard! Just like the wind!

Debbie was proud of herself.

“You must have. Just as though the devil was behind you and not inside you,” laughed Thelma Scace.

Both girls checked their pace and looked at each other.

“What’s wrong girls, don’t like my joke?”

“Mummy, you’re always teasing. You tease too much sometimes.”

“Okay, if you think so. Now come in and have something cool to drink.”

“Oh, thanks Mummy, you’re good!” Debbie rushed in ahead.

“Everything alright, Lindy?”

“Yes. But we saw kind of funny things in Burnley…”

“Well, come on in and tell me about them.”

Linda went in with her Mother, and the two girls described the strange shapes at Burnley. They thought it was safe enough to talk about them. If they were not there when their parents passed by next time, the girls could say they must have been taken away. But it was more difficult to explain the incident at Drumlin Hill, so they kept quiet about it, as Linda had suggested they should. The rest of the afternoon passed peacefully enough, and by supper their father was home.

Albert Scace was a large red haired man in his early forties, vigorous in his movements. He was very sentimental about the countryside in which he had been brought up, and in his work for the Conservation Authority he was passionately concerned to keep the beauties and amenities of the countryside. He knew every road and sideroad in the country and many road allowances which had never been used as originally intended. He was also interested in local history. So Linda thought she might bring up the subject of Drumlin Hill.

“Dad, we rode up Drumlin Hill today.”

“Good.”

“Do you know much about Drumlin Hill, Dad?”

“A drumlin is a land formation, also called a whaleback. We’re on a drumlin right here.”

“Have the Wrights always lived at the foot of Drumlin Hill in that log house?”

“They came about a hundred years ago and settled that farm. Old Robert Wright died from hauling too many stones off the field, they say. But it’s not as old a farm as this.”

“How old is this farm, Daddy?” Debbie got her word in.

“About a hundred and seventy five years. Way back before your time, Pudding.”

“I’m not a pudding! Daddy!” She giggled.

“Was it Scace’s then Dad?” asked Linda.

“No, O’Melias. Then one of them married a Scace and it’s been Scace’s ever since.”

There was a short silence. Then Albert looked at Linda.

“What makes you think Wright’s house is log? It’s covered with brick siding.”

Linda was embarrassed.

“Oh. I just figured it was. Isn’t it?”

“As it happens, it is. I just wondered how you knew.”

Debbie came to Linda’s rescue.

“Daddy, may I be excused, please, and Lindy too. We want to watch TV.”

“May they be excused dear?”

“Yes, off you go. All that riding has given you good appetites – there’s hardly anything left on the table.”

Once or twice in the weekend that followed Linda and Debbie talked idly about the strange thing which had happened to them at Drumlin Hill. Debbie, who had been the most visibly scared — audibly too — seemed to forget her fright the more quickly of the two. The incident dimmed in her memory as she preferred to think of the fun she had getting home so quickly after it. Linda, on the other hand, pondered. What had happened to them was frightening, skin-tingling, but not menacing. They had not been in any danger, as far as she could tell. The black-dressed man on the big horse had been stern, but had seemed full of urgent concern for people at the farmhouse. Besides, he had not seen them.

It was Monday morning, dawning bright and hot, which put it into the girls’ heads to take another bicycle ride, and this time to take their lunch. There was considerable joking with their mother over the lunch, as the three of them recalled the disastrous twenty-four hours in June had begun with them taking their lunch. But now they were all confident in the walkie-talkie system, which was always carefully tested before the girls went on their expedition.

“Which way are you going today, girls?”

“First, down to Warkworth, then to Bantytown. We’ll probably have lunch by the waterfall if it’s the right time. Then, either up the hill and back by the cheese factory, or up the hill and back by Drumlin Hill.”

“Yeah, we’ll be grumblin and tumblin by Drumlin Hill.” said Debbie.

“Well, don’t fall into the Bantytown pond.”

“Maybe we’ll sneak a swim there, Mum.”

Both girls were expert swimmers, and had learnt to swim in that very pond. That was in the days of the former owners, who had encouraged swimming there. But the most recent owners — though they owned only one side of the pond — were less hospitable. In any case, the main Warkworth Pond was now admirable for swimming. But kids liked to take a dip by the old dam, as often as not a skinny dip, just to taunt the new folk.

“Anyway, don’t overdo it. It’s a very hot day, and I think you were over tired when you came in last week.”

“Okay, Mum. Bye.”

“Bye-bye, Mummy, mummy-mummy-mummy-mum.”

“Bye, kids.”

Thelma wasn’t going to garden in the heat today. She went about her household chores, and hoped to have a good read. Her favourite woman novelist’s latest book, “The Witchers”, was just available from the Regional Library.

The girls coasted down the hill, and then around the slow turn. The Cemetery came in sight, on a little hill of its own. Behind that loomed the lovely landmark of the village, the evergreen forest rising behind the pond. The spire of St. Jerome’s was off to one side, and the whole village lay spread beneath them. After they passed the cemetery, joking as they usually did about the elaborate television aerial which rose right above one of the more pretentious gravestones (it was really attached to a house on the other side of the hill), they reached the nursing home, which had been the old school for many years, and passed by the marvelous giant sunflowers grown just across from the Bantytown Road. They didn’t take this road yet, because they were going in to mail an urgent letter which had missed the post, and to get some pop for their picnic.

There were already children and teenagers swimming, and the Scace girls stopped to chat. Debbie, who was very popular, soon had a whispering coterie of girls giggling around her.

“Wanta swim here instead, Deb?”

“Nope. Let’s go.”

Linda was surprised. Debbie usually preferred a giggle with the town girls. They walked their bikes past the former inn, recently restored, and then over the bridge. There was the BeeHive. Its rounded roof made it look like a second world war hut, but it really was well over a hundred years old, and had once been the first post office in the village. Linda stopped to buy the pop, and Debbie cycled down the street to mail the letter. Soon they were ambling slowly up the mill street, their baskets full of lunch and pop.

“Didn’t want to stop with the girls today, eh, Debbie?”

“Nope… Lindy?”

“What.”

“Can we take a peek at the Hairy Hippies today?”

“Oh, so that’s why you don’t want to stay in town.”

“Yep.”

“I suppose you want to skinny dip with the Hairy Hippies?”

“No, Lindy, don’t be silly. I just want to see them.”

“Mum said to stay away from them.”

“She didn’t say so today.”

“Well, she said so, and I think we shouldn’t do things behind her back.”

“We didn’t tell her about Drumlin Hill.”

“So?”

“So we kept it behind her back.”

“Don’t be silly, we didn’t do anything at Drumlin Hill.”

“We won’t do anything with the Hairy Hippies. Least, I won’t.”

“You certainly won’t, ‘cause we’re not going there.”

“Are so.”

And so the argument continued, with Linda getting more and more short tempered as she got angry with herself as well as her sister. Why did she feel so fierce about the Hairy Hippies? Or was it really a feeling she had about her sister and her lighthearted attitude.

The girls went slowly along the Bantytown Road, which went at a sharp angle from the county road just at the nursing home. They followed the river, more or less, and new suburban type houses were strung along the way. Finally they came to the lumber yard, and then, instead of crossing the bridge, they went along a track to the dam. It was much cooler in the shade of the cedars which overhung the banks of the pond, and the girls settled down to have their picnic.

All thought of a swim had gone, and Debbie chattered on about all the things she saw, the birds, the fish she thought she saw, how the water splashed. She was a good observer of nature and people, and her eyes were directly connected with her tongue.

Linda was accustomed to the chatter, and ate cheerfully to this accompaniment. She wasn’t thinking about anything very much, just enjoying the perfect relaxation of hot August and an increasingly full stomach. So she was off her guard when Debbie, still having in mind a visit to the Hippies’ Pond, suggested that, instead of going up the hill and back by the cheese factory, or back to Drumlin Hill, they continue up the track.

The track was really an undeveloped township road, excellent for skidooing in the winter, and passable by trucks or jeeps in the dry season. Debbie’s idea was that this would be a quicker way to Drumlin Hill. She avoided telling Linda that the track did not lead all the way to Drumlin Hill and that they would either have to go to Hippies’ Pond or backtrack through a farmyard to the concession road, to reach the scene of last week’s adventure.

Linda dozed a little, sitting there on the dam, with her toes in the water, and the buzz of flies around her. Suddenly, she noticed Debbie leaning too far over the water, and woke with a start.

“Debbie, watch out! You’ll fall in!”

“I’m okay, Lindy.”

“It’s time we left anyway. Let’s go.”

Debbie bounced cheerfully over to the bicycles, taking the picnic remains with her, all obedience. She had made Linda think she was still running the show, but Linda had been hoodwinked into doing what Debbie wanted anyway. That was often possible, she knew, at mealtime, once Linda passed her initial hunger.

There was a slight incline up the track, and they took it slowly. The track followed the river, and then gradually turned inland. It was delightfully overshadowed by evergreens on the hill above, and then an assortment of poplars and birches. Species of ground cedar and juniper tried to push onto the road itself, which was never graveled, and orange hawkweed was growing in many places in the woods. In several clearings where the sun got through, butterfly weed, a form of milk-weed, brightened their path. Debbie was riding a little ahead, singing a song to herself, and Linda wheeled comfortably along behind.

“Look, Lindy,!” Debbie stopped and pointed, “Isn’t this what the boys call Hidden Field?”