The Topher

by Graham Cotter

Councils of War

Illustration by Audrey Caryi

The Topher rode along behind the two girls on the way to Norham. They had been outraged with their mother when they discovered that new arrangements had been made without consulting them. They had some difficulty being civil with their grandmother, the cause of the change of plan. But after the Topher came to meet them — they greeted him with dark looks — and they had ridden along the top of Scace’s Hill out of sight of their house, he stopped them and called them around him. His recounting of John’s meeting with Martha had restored their good cheer, entertaining Debbie immensely. But they still had some nagging questions to ask.

“What about last night?” Linda had said. “We won’t know if John actually got to Master Comfort with his message.”

“Yeah, maybe he spent the night with Martha instead,” Debbie had put in.

“Hold it,” the Topher had replied. “Chances are you are going now to see John and the things that happened in what you call ‘last night.’”

“How come?”

“Because, don’t you see, our time is not the same as their time.”

“But we found John the first time when it was morning for him and morning for us!”

“It’s not the time that matters. It’s the place.”

“So we are going to Curtises’ place?”

“We’ll start there. But we have to work out a few things first.”

“What kind of things?”

“Well, I can’t go where you can’t go. I can only see things through John. By the way, do you have both the radios?”

“Yep.”

“Debbie, can you work it as well as Linda?”

This was the wrong question to ask.

“Any day,” she replied. “Linda just works it all the time ‘cause she thinks she’s so important.”

“Look here,” the Topher was beginning to get angry. “You’d better cut out squabbling! John’s life and maybe others’ will depend on you doing just what you’re told.”

Then, calming himself, “So please, please, be serious.”

Debbie looked at him sideways, wondering how far she could go in teasing him, and decided to be serious.

“Okay.”

“When we get to the right place for you to go back, I’ll just stay in that place. I’m sure I’ll be able to be with John. But you must agree now, that Debbie will stay with John and the rebels, and Linda will go to where she can find Major Campbell and the redcoats. You must keep your radios at the ready, and try not to push the button that will call your mother. She thinks it’s a game, but there’s no need to explain more to her than we have to. Also, John can hear the radio, though it seems the others can’t. If you talk too loud on it he’ll get scared and do something foolish. Okay?”

“Okay.”

“Yep.”

Debbie gave him a look of adoration, which he tried to ignore.

Now they were pedalling up the same hill where they had met McQoid the day before. There had been some puzzled looks as they rode through Warkworth, since both the mayor and McQoid had talked about the strange trio. There was general suspicion of the Topher, not so much because of his long hair — the fad had come to Northumberland County in due course — but simply because he was another of the city folks who appeared, especially in summer, and did strange things like living off by himself in a tent.

“What’ll we do, Tophy?” said Debbie.

“Just keep trying. Let’s walk down this gravel road.”

The road they took, pushing their cycles, was the old main way from Curtises’ to Norham. It was now the continuation of the new road through the Works yard.

Norham was very peaceful ahead of them, scarcely a soul in sight. A man was tending a beautiful bed of peonies just past the first intersection, and gave them the usual wave of greeting. The next intersection had a supermarket in an old brick building. There was also a church-like structure which seemed to be used as a store. The Norham road, which this was called, came from the same schoolhouse where they had had earlier adventures witnessing the drilling of the redcoats, and went on to the poultry farm. They stood, uncertain.

“Let’s go to the Norham Pond,” said Debbie.

“No, it’s dangerous,” replied her sister.

“Anyway, that wouldn’t be where Stone’s Tavern was,” said the Topher. “And there wouldn’t be any action over there. Just milling.”

“Let’s go this way,” said Debbie, starting off towards the poultry farm, riding before anyone could stop her.

The other two mounted their cycles to keep up with her, both annoyed, but not wanting to make a fuss where there might be people looking at them from inside the houses. Debbie wheeled along, then turned left down a gravel road. This led past one or two houses and flourishing vegetable gardens. Some small children waved tin pans and a small butterfly net at Debbie, but she swept past them. Then she slowed down as she came to the last house.

The road itself dipped into a ravine, where it met a tarred road. But before the dip, there was a lane at right angles, which disappeared into some bushes higher up the ravine. Debbie rode in there and then walked her bicycle, waiting for the others to catch up with her.

Mrs. McAndrew was looking out her window as the children and the young man went by. She noticed that they turned up the old disused lane.

“Funny,” she said to herself. “Them’s Scace’s children and he must be that young man I’ve heard about.”

So she went out on her porch to watch. The three were all together walking into the bush, and seemed to be arguing.

“Now what mischief are those children getting into? Them’s the ones that disappeared last June, and we thought they were dead. Up to no good with that older boy.”

Then she stopped short, for the two girls disappeared before her eyes, bicycles and all. The ‘boy’ was still there, but he was stock still and seemed to be listening.

“My goodness, I suppose it’s some game. Still, I’ll just keep an eye on him.”

She was in for a long wait. From the girls’ point of view the change was not much of a surprise — at least, not from Debbie’s point of view. She felt she was heading into the past anyway. Norham was old, and many places where houses had once stood were now empty. She had always wanted to explore this old lane. So, when it suddenly became a rutted road, which cleverly dipped into the ravine with no bushes, and came up the other side into houses, she was rather proud, having led the others, as she hoped, back to John.

As she followed, Linda became less angry with her sister, because it seemed to her that sometimes Debbie had the right instincts. She did not take time to notice the scenery, because she found she was standing right beside John, who was walking with a crowd of men telling his story.

“And you see, Master Comfort, they know what we plan, and they plan to be ahead of us.”

“Did you tell them, boy?”

“No sir, no sir, I did not. I heard them say I was to be taken and held in jail!”

“Mor’n likely shot,” said another man.

“Don’t discourage the lad!” said Comfort, turning fiercely on the other, Emmanuel Ellerbeck.

“He’s done us great sairvice, and we’ll see he comes to no harm!”

John was visibly cheered by this assurance, coming as it did from the fierce rebel who was also his Martha’s uncle. Then he caught sight of the girls beside him and shuddered.

“Cheer up! Have faith! When we have Reform, you’ll have a medal for saving the great rebellion of Norham!”

“Never mind the lad, now,” said another man, the red-faced blond one the girls had seen at Curtis’ house before. “What are we to do about this?”

“If they are assembling at one hour before noon, then we shall assemble two hours before noon.”

“But Master Comfort,” said John, almost afraid to speak out, “I heard the Major say he had information of our meeting at noon. If he had information about our meeting then, he may have information about our plan to meet earlier.”

“The lad is right,” shouted Comfort, stopping the group in the middle of a log bridge which crossed the stream. He stood, fists shaking by his shoulders, his fox-like face fiercely moving as his eyes went from one man to another.

“Among us there is a traitor! We have been betrayed once and may be betrayed again!”

“No, Comfort, that need not be,” said a short dark man. “With word going out to so many of us in Percy and Cramahe some person not of our beliefs may well have overheard and passed it on.”

“True,” said Comfort, calming down a little, “ours is a people’s movement, and the word passes around from one eager reformer to another like fire in a dry meadow!”

Some younger men on the edge of the group raised their hands and shouted, “Reform! Reform!”

“So,” continued Comfort, “we shall take no rest at all. From this moment and this place we shall not disband, but send out word that all must come as soon as they may.”

There followed some long instructions, not much that the girls could

follow.

“Edward, you to Barnabas Brunson, Michael Cassidy, Abraham

Cronkite, and their sons and working men!”

“James, you to Rudolf Whitney, Amasa Brunson, Elihu Lincoln, and Samuel Tuffie!”

And so the list went on, and the younger men were sent off with their instructions.

“Master Comfort,” said John, “I should get me back to Master John’s and Miss Martha.”

“No, boy, you dare not! Our home is too close to Percy Mills. They may already have posted a guard to take you. I shall send another to see to the safety of my home and folks, before the redcoats burn all to nothing.”

At this John recoiled in fear, thinking of his Martha, and the girls each took John’s arm sympathetically.

“We won’t let that happen,” whispered Debbie, forgetting that the others could not hear.

“And don’t show you know we’re here!” snapped Linda, pinching John’s other arm.

John looked from side to side, his face first sagging in fear, and then beginning to smile. The Topher who saw all this in his mind’s eye — as well as through John’s eyes — felt a sudden surge of emotion. John was, it seemed, appealing to him, the Topher, that godlike creature he had briefly glimpsed. Topher felt a drain on his strength. But it was not the painful tug of John’s fears and disappointments he had felt most of his lifetime, until his obsession with John had become, not only a puzzle to his usual workaday self, but something he resented. Now the strength pulled from him was what he was glad to give. He felt John’s appeal for help and warmly responded. It was a feeling like love.

Ellerbeck, the only one of the group who had observed John’s reaction, saw a new John emerge from the fear and anxiety. John suddenly straightened — in fact he wriggled free from the comforting arms of the two Little People, and did so without fearing to offend them. His eyes opened wider, as eyes often do when their owner is angry, and the light glistened from their surface.

“That boy’ll be a man before this is finished,” Ellerbeck said to himself.

Linda, after being brushed away, noticed the change too. She beckoned to Debbie,

“Remember, we have to split up. You stay with John now. I’m going back to Wark- Percy Mills. I’ll go past Curtises’ and see what’s happened. As soon as I have some news, I’ll press the buzzer. Tell John what we’re doing, if you can make him understand that the noise of the walkie-talkie is part of the way we talk to each other and not something to frighten him.”

She was breathless.

“S’pose he gets scared?”

“I don’t think he will. I think the others are giving him courage — maybe we are too. And remember; don’t get walked over by someone who can’t see you’re there. Or shot.” Linda was again appalled at the possibilities.

“Okay, little Mummy, I’ll behave!”

Debbie skipped off teasingly, and nearly hit Emmanuel Ellerbeck full in the stomach. Fortunately, she did little more than produce a small breeze near him, but Linda stood still, shocked. Debbie steadied herself, put her finger to her lips and waved to Linda. The older girl sighed, shrugged her shoulders, and turned.

By the time this exchange had taken place between the two girls, the little group had passed beyond the ravine, most of its members scattering on their errands. So Linda had the greater part of the road to walk back until she regained the point where she had disappeared from Mrs. McAndrew’s sight, and where also the girls had left the Topher. As she reached this spot, there was a sudden shaking of the air around her, and she found herself back in modern Norham. She was just behind a tree, and she witnessed a strange scene.

The Topher had apparently been standing quite still for some time on the very place they had left him. What Linda saw was her friend, his face happy and relaxed, and his eyes shut, but deadly pale. Mrs. McAndrew, whose curiosity could take no more suspense after she had watched him for fifteen minutes, was approaching along the lane, calling out,

“Boy, are you sick? You’re as white as a sheet!”

The Topher responded by sinking first to his knees, and then falling slowly alongside his bicycle. The woman rushed to him, clucking like a hen and saying things about people who didn’t eat enough potatoes.

“Are you alright, are you alright?”

She shook him.

“Oh! Oh! Who? Yes, thank you. I must have fallen asleep!”

“Fallen you certainly have. Have you hurt yourself?”

“Oh, no, thanks.”

He brushed the dirt and gravel from his arms and legs.

“Come; let me fix you some tea. You need something sweet for strength!”

“Thanks. Thanks very much. I will.”

He stood up.

“What about your two friends? Them Scace girls?”

“Oh, they’ve gone along the old lane. They’ll be back.”

“Why goodness sakes, that hasn’t been a lane for fifty years or more. Was all grown over when I was a girl. They’ll be into poison ivy and I don’t know what!”

At this point the Topher caught sight of Linda over Mrs. McAndrew’s shoulder. Linda moved as if to come to him. He shook his head and tried to show her she should not.

“What’s there?” said the woman, turning around.

At that moment, Linda had the good sense, or luck, or management, whatever it was, to go back to 1838, bicycle and all, so Mrs. McAndrew just had one of those spine-chilling experiences you have when you think you see a person

and it turns out to be a shadow or a tree stump.

“Oh, nothing. I was just getting myself awake.”

“Goodness sakes, there’s something queer about those girls. Never know when they’re going to be somewhere you’re not expecting. And then all that funny

business when they ran off this June. You weren’t here then.”

She looked appraisingly at the Topher, wondering again what he was doing

with youngsters so much his junior.

“No, but they told me about it. And Mrs. Scace has a two-way radio she

uses to talk to them, so I don’t worry about them when they go off.”

“Two-way radio indeed! I don’t what my old mother would say. Girls

that age should be at home.”

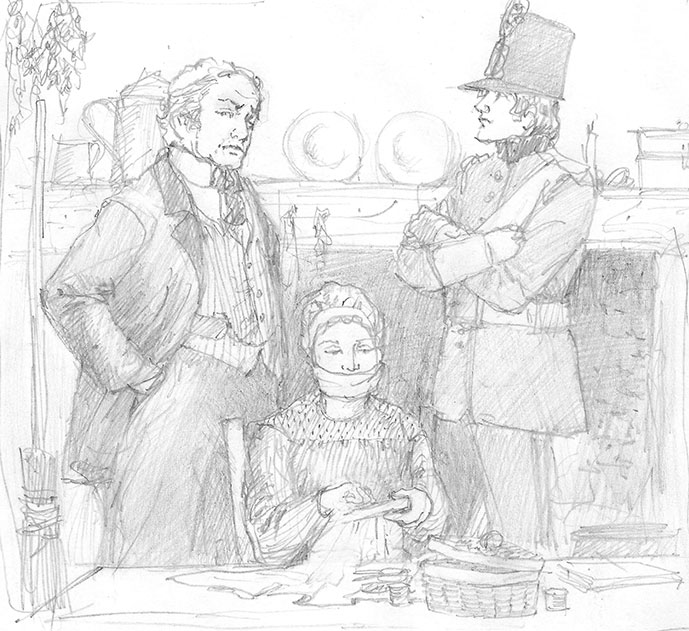

Linda was not sure how she managed to return to her adopted time and to her present task, except that she’d realized that the Topher was alright, and that she was needed in what she was doing. The road was too rough to ride her cycle very much, but she went as fast as she could through Norham, past Stone’s Tavern at the corner, and up the hill to Sugar Grove. By now it was getting toward dark, even in that old-time June, and she could see a light in the window of the house, a candle in a shade, she realized as she grew closer. She went boldly to the window and looked in.

Illustration by Audrey Caryi

Martha Curtis was sitting at the table, her mouth gagged with a towel, and Sergeant Cameron and another redcoat were standing over her.