The Topher

by Graham Cotter

Percy Mills

Illustration by Audrey Caryi

The Topher got up and walked towards them smiling broadly. But before he could say anything, Debbie turned to her sister,

“How was it, Lindy,” she said,” that the Topher’s bicycle was with us when he wasn’t?”

“I don’t know. Topher, did you look up at the bikes at all, while we were there?”

“I didn’t look at all, except at what John was seeing.”

The girls thought about that for a moment, then Linda asked,

“When did John first know we were there?”

“I think,” said the Topher,” I think I began to see through John’s mind when I was still talking to you — when I said ‘John is getting into the politics of his time,’ or something like that. And I think he heard you say ‘And I like you too, Topher,’ only he didn’t know what ‘Topher’ meant. It seemed as if he said ‘Shhh’ about then because he was afraid you’d be overheard by the soldiers.”

“What about the bicycles?”

“The image in his mind was of six wheels, and he saw all three bikes. But he didn’t recognize them. He saw them as the wheels in some Bible story about a vision.”

Debbie began to dance,

“Ezekiel saw a wheel a-rolling, way in the middle of the air. And the big wheel moved by face, and the little wheel moved by –”

“Faith, not face, Debbie!”

“And the little wheel moved by the grease of God, all in the middle of the air.”

“What did you think of it all, Topher?”

“It was great! It was just like having a moving picture or TV rolling in front of you at the same time you are part of the action yourself. Only, I felt as though the whole inside of me was being wonderfully pulled out of me, right through the top of my head!”

“Sounds pretty silly to me,” said Debbie, “What a mess you’d look with the whole inside of you pulled out of the top of your head!”

“Shhh! Debbie, it’s serious,” said Linda.

“So I really feel different, just like I used to when I dreamed of John, all the time” —

“And before Mary” — put in Debbie.

Topher scowled and went on.

“I know we have to do something important for John, and that I met you two so that you could help me.”

“The important thing we have to do now,” said Linda,” is do John’s spying for him so that he doesn’t get killed.”

“Gee, if he got killed I’d feel dead myself.”

The Topher was certainly emotional about his dream life, Linda thought. But then, John had also become very important to her and to Debbie. Stupid as he was they had to look after him, as after a dumb animal. She spoke out.

“We seem to be able to meet him easily enough, by going where we would expect him to be.”

“Let’s go into Percy Mills – I mean Warkworth,” said Debbie, “and maybe we can look at the house the officer lives in.”

The three set off along the county road to Warkworth, the Topher riding a little in the rear, for road safety’s sake. There was a dip in the road, and then a rise, and from there Warkworth lay ahead of them, a different view than that from the Norham road. Now the cemetery was the backdrop and the tree plantation, on their right.

The Topher stopped to take in the scene, peaceful as it was, yet with a sense of quiet industry. Just then a car passed by, kicking up dust as its wheel touched the shoulder. As the dust settled, he looked where the girls had gone ahead, down the hill.

No sign of them. He raced down, looking in the ditches as he went, afraid the car had thrown them off the road. There were neither girls nor bicycles to be seen. Then he stopped and laughed.

He realized they had slipped back in time again, to fulfill their mission in Percy Mills. And John was not with them or he would know. So he now had more information about time change. They really could not be in two times at once. Yet they could talk to their mother on the radio, no matter which time they were in! The more he tried to figure it out, the more confusing it was. Nothing in his science studies in school came to his aid. He could only remember an Irish joke his father used to tell, though nobody ever seemed to get the point. Sir Boyle Roche, speaking in the Irish Parliament, said solemnly,

“You cannot be in two places at once, unless you’re a bird!”

The Topher wondered what kind of bird could skip back through the years as these two children could. They were really quite little children, for all their accomplishments.

That reminded him of something else, just what he could not remember, about little children. He did not puzzle long, but returned to his happy mood and enjoyed it while it lasted.

The girls, meanwhile, (if “meanwhile” is the right word, as it wasn’t meanwhile at all, but some other while) had scarcely noticed any changes around them, for they had dismounted their bikes to look at the view, too, and that was good, or they would have been thrown off by the terrible road. They had been talking about their brothers, as it happened, and whether they were having a good time at camp, and had stopped noticing the scenery for a few moments.

They realized that they were pushing their bikes over deep ruts, that the one whole side of the road was heavily wooded, and looking up, that the view of the village was now quite different. There were trees everywhere. They wouldn’t have recognized the cemetery hill, for it was heavily wooded, with a scar going up and over it where the concession line — never fully developed into a road — went across the hills. Instead of the reforestation on the right was an old pine forest; there was no steeple of St. Jerome’s, nor could they see much of the village, just trees.

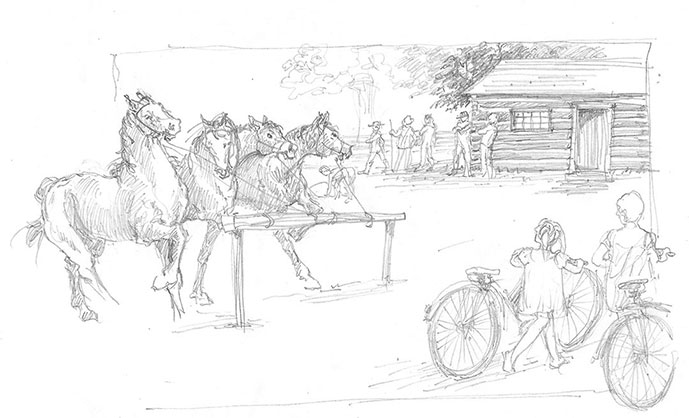

Wide-eyed, they pushed their bikes on. A rough wooden bridge crossed the river on the flats, and then they saw a clearing on the left. As they grew closer they noticed a great buzz of activity in the clearing. There was a large log house with two wings, and stables. People had just ridden in on some horses, and were tethering them at the stables.

“This must be where the big brick house stands now,” whispered Debbie.

“That’s right. It used to be an inn. But you don’t need to whisper; they can’t see or hear us.”

Linda was not quite right. It seemed that in their time-change they had a special affinity for horses and other animals. For the horses, about five of them, began to rear and whinny, and some rough looking dogs rushed out barking, the fur along the ridge of their spines standing up. It was just as though they could see them and as the girls — trembling in spite of their invisibility — pushed past the inn, the dogs’ eyes and howls followed them. But the animals were themselves too terrified to come within twenty feet.

In the meantime, their owners shouted at them to be quiet. Two men strode forward, looking straight at the girls but not seeing them.

“‘Tis early yet,” said one, “for the beasts to be crying so. I wonder if they smell a bear or a wolf.”

“Perhaps they smell a rebel or a Yank.” said the other.

The girls moved on, wide eyed. They would be able to tell a lot to the history teacher now, thought Linda, though it might be a little difficult explaining where they got their specialised knowledge. She remembered that her father had nearly caught her out through her knowledge of Wrights’ log house near Drumlin Hill. Now they came to a place where a rough track went off to the left. Someone had begun to clear a lot, and to put down foundations for a house. Then another path to the left, better cleared, and on their street, which went back at a sharp angle, there were two or three rough houses, surrounded by vegetable gardens, and fruit trees. Next they were at the corner of what they knew to be Main Street, for here on their left was the BeeHive. It did not yet have a galvanized metal roof, but wooden shingles, and that same long look of some kind of mailbox. That was appropriate enough for it was the post office long before the rural delivery of mail began.

They looked down the street. It was wide, with corduroy showing the length of it, and big trees lining the farther end. Near them, apart from the BeeHive, there was one other brick building, the bricks very new and yellow. Down the middle of the road came tramping Major Campbell’s militia, the Major himself in front with drawn sword.

“Oh Oh! There they come, Lindy!”

“Look out Debbie, don’t let them walk right into you.”

They scampered to one side, as much as they could scamper over a rough road with two bicycles built for much better surfaces. The soldiers marched past them and wheeled left, then across the old wooden bridge.

“What would happen if I didn’t move?”

“Then you would get trampled and hurt.”

“But they can’t see me.”

“Seeing and feeling are two different things. If we can feel this rough road under us, you bet we’d feel their rough boots walking over us.”

“It’d be a big surprise for them, walking over things they couldn’t see.”

“It’s a surprise I can do without, thank you,” Linda imitated her mother.

“Now, let’s follow them.”

It was a strange sight, if there had been anyone then capable of seeing it with a twentieth-century eye: the uniformed militia of redcoats with their antique guns marching along the pioneer village street, followed by two little girls with clothes and bikes from the 1970’s. Linda was aware of their strange position. Debbie thought it was fun, and was not too much bothered by contrasts.

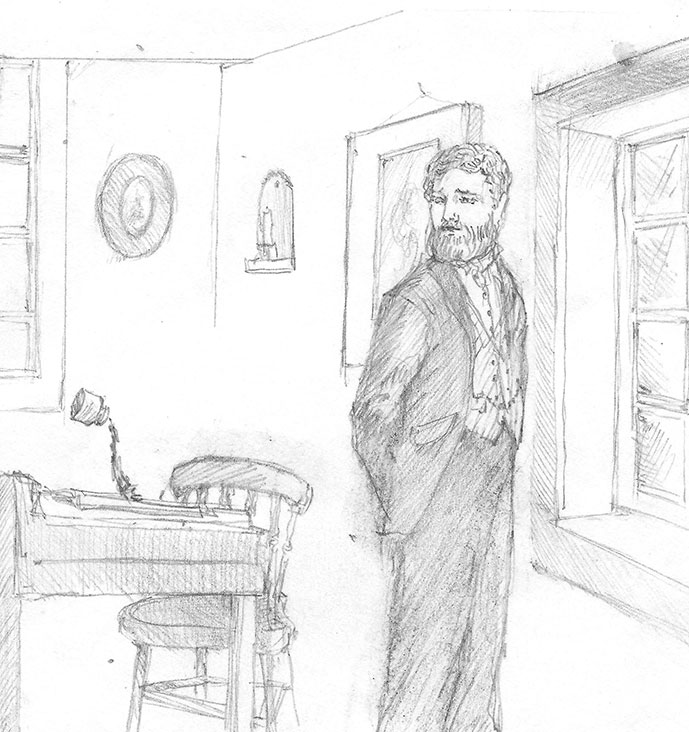

Just beyond the bridge was a fairly new house, built close to the road. As John said, it had been built with new sawn lumber, and well built too. It was two-storied, with a two-storey verandah at the front, and plain broad windows in a Georgian style at intervals. There was ornamentation over the main door. Here the militia stopped at the command of the Major.

“Stand at ease. Sergeant, come with me inside.”

The Major turned to go in and Linda, leaving her bike on the ground grabbed Debbie:

“Come on, we have to hear what they’re saying.”

They followed the Sergeant in, just getting inside the door before it was closed. It would have looked very strange opening and closing all by itself a few moments later. Inside they were led up a fine staircase. Linda could see the downstairs was living room and kitchen. A warm smell of cooking was coming out of the rear part of the house. Upstairs there was a spacious living room. The furniture was not as plentiful as in the pictures she had seen of Victorian houses: a desk, two chairs and a table had clearly been brought to Canada from over-seas. The remaining chair and table were of local make, pine and rather simple compared with the old country furnishings. There were pictures on the walls — a great snow capped mountain, painted in oil, and a very royal fat gentleman in a large print.

Linda guessed it was one of the Georges, the Kings before Victoria. It was, in fact, King William the Fourth, who had recently died and been succeeded by his niece.

“Sergeant, at ease.”

“Thank you Sir.”

He was clearly Scottish, his voice less markedly so

“Sir, begging pardon, yon highland, is it not Ben Nevis?”

“Yes, Cameron, indeed.”

“Many a happy day I spent there as a lad.”

“Oh, really, Sergeant? We have much in common, then. My mother painted that landscape.”

“`Tis excellent, Sir.”

“Now Cameron, to business. I have had information that the Norham rebels will be assembling at Stone’s Tavern tomorrow morning by noon. Therefore it will be too late if we march again tomorrow night. You are to tell the men, separately, and bind them on oath to secrecy, that they are to assemble one hour before noon tomorrow. Never mind the harvest or whatever they are doing. If we do not repulse them our crops and barns are lost anyway.”

“`Tis that serious now, Sir?”

“Yes, and we cannot expect help from York before the rebels raise their standard of mutiny.”

“Then what will be our plan, Sir?”

“We shall advance from the southern bridge on Main Street, where we shall muster at eleven, along the King’s Road — Queen’s Road I suppose it should be called — to Norham, passing by Curtis’ house and securing it from contact with the tavern. Then we shall advance upon Stone’s at the crossroads. We must first intimidate them, for they are more numerous than ourselves, and would be very dangerous if mustered in strength.”

“But, they are not armed, Sir! And we have our good muskets and shot!”

“True, though some of them will have hunting pieces. But it is better to scare them off than to cause bloodshed. We do not want to reopen the civil war of last year, even in defence of right. It is a last extreme to break the peace to heal a breach of the peace.”

“If you say so, Sir!”

Cameron was clearly of a different opinion, and thirsting for blood.

“And, Cameron, there’s another matter. I have reason to believe that young man, McCracken, is it?”

“I think it’s Quackenbush, Sir.”

“Quackenbush? Well, that boy who hangs around Curtis’ place. He’s been spying on us, stands around looking at everything we do with his mouth hanging open. Find him, and put him under close guard until the countryside is settled. We don’t need spies around here.”

“In the war we shot them, Sir, if we did not have time to kill them with the sword.”

“Remember, Cameron, these are our fellow countrymen. We do not wish to

kill them, only to keep the peace, the Queen’s peace.”

“Sir,” said the Sergeant, who had hardly been at ease. He drew himself up, saluted so that he nearly knocked off his own fur hat, stomped his foot, and marched out of the room. As he went down the stairs, to keep up the rhythm of his march without taking two steps at a time, he raised his knees high, and made thunderous stomps all the way down.

Debbie turned to Linda. “I’ve always wanted to be a ghost and play tricks! Let’s do something to the Major.”

“No, Debbie, that’s childish. John may get caught or shot if we do not warn him. Let’s go.”

She pulled at her sister. Debbie, determined on mischief, wriggled free, and running to the Major’s table, upset his inkpot.

Illustration by Audrey Caryi

The Major, who had been looking out the window with his hands behind his back, turned around in time to see the inkpot rise up, apparently unaided, pour its contents on the table and fall. Then there was a motion of the air like a breeze, and the door slammed. He was about to call out, thinking quite rightly that some enemy was playing tricks on him, when there was a worse commotion downstairs and outside.

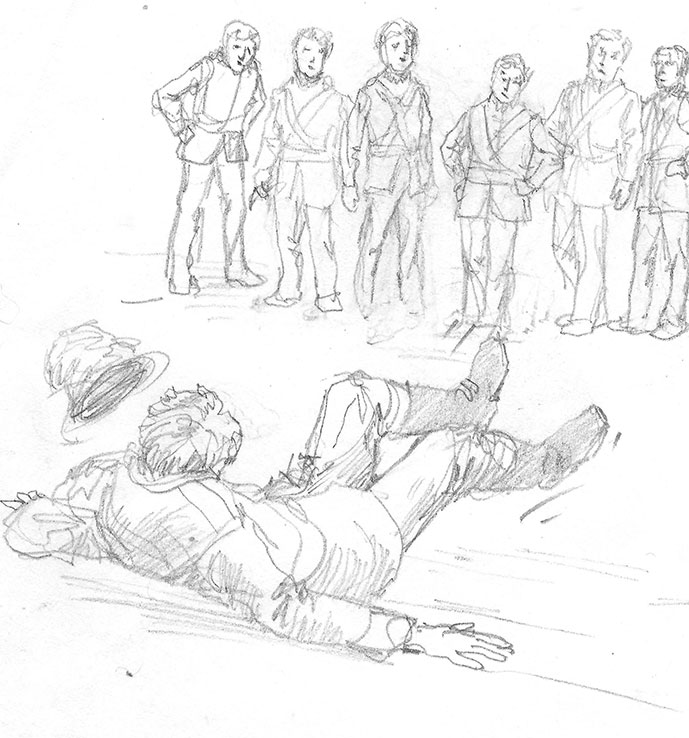

The Sergeant, full of vengeance and remembering action at Waterloo, marched down the stairs, prepared to smite his enemies. He moved outside with his soldierly stride, high raised knees and upswung arms. His troop expected the order to attention. On came the Sergeant, tall and grim, a thousand years of Scots determination to fight against, — or for, if it paid — the dirty English, finding its finest hour in his determination to put down the Sovereign’s foes.

What he did not know, however, did hurt him: for directly in his path

were two space vehicles from the future, the girls’ two bicycles, left in a tangled heap just beyond the verandah. The handlebar struck him sharply on the shin. By this time his other foot was airborne, and moved forward — staggering somewhat like a moose who feels the impact of the hunter’s shot — to land, not on firm ground, but on the pedal of Debbie’s machine. The pedal swung, the foot moved on and was caught, as a hare in a trap, by the gear chain.

Cameron, no longer provided with any means of remaining upright, fell, like a great hardwood tree in the virgin forest, his hands before him like branches, his fur helmet flying across to his platoon as if he were signalling for help. He met the ground with his torso, his legs deceived by what seemed to him and his soldiers to be the firm earth, the solid ground of their daily life and expectations. His men were aghast at his downfall, as they saw his legs and feet go up into the air, in part dragging with them, and in part being held back by, the unseen machinery of the Little People. Cameron, fighting an unseen enemy, drew up his knees to kick off the metal snakes which seemed to be attacking him, but the bicycles, as bicycles will, fell upon him.

It was at this point that Debbie and Linda came out the door, whose opening and closing by invisible hands escaped the notice of the startled troops. The girls could at once see what was happening, and they rushed to the Sergeant’s aid, giving him directions about how he should get untangled. Alas! their words were no more audible than his attacker was visible, and it was some minutes before they were able to rescue the machines and the Sergeant from the entanglement.

Illustration by Audrey Caryi

But not before the Sergeant had roared to his men that he was attacked by the devil and they must shoot that demon or he would be away to hell. However, the rustic militia — whether because they feared they might shoot their Sergeant, who was wrestling with the air before them, (and who might well, in even such a short time, have had a drop of the Major’s whiskey) or perhaps because they were entertained by the thought that their fierce warrant officer was being dragged off to hell — had made no move except for their facial muscles, in various expressions of horror, amusement, or surprise.

The reactions of the two interlopers from the twentieth-century were quite different from those of the soldiers, and also different from one another. Linda stood aghast at Cameron’s disaster, not for great sympathy with the Sergeant, who was, after all, their enemy, (or the enemy of the cause they were supporting) but because their carelessness with the bikes had led to a situation which could lead to their own defeat. Suppose the soldiers began firing at the invisible machines? And suppose a stray bullet were to hit one of them? Would it be possible to die back here in the eighteen hundreds? Or suppose one were hit and wounded, how would she get back to the time in which they belonged for proper treatment? They would have to be more careful in the future.

In fact, a glimmer of doubt arose in Linda, as she realized they might in fact be present later when there was shooting. Debbie, on the other hand, was delighted. Nothing on those long Saturday morning cartoons of cute animals by which TV desecrates the ancient Sabbath, had been as funny as this. (Debbie did not think those words about the Sabbath, but Saturday morning, especially in winter, was an opportunity for her to take time off from reality in front of the mind-emptying machine.) She jumped up and down and shrieked with laughter, unnecessarily pointing out to her sister each adventure that took place.

Finally, she rolled in the dust of the verandah in hilarity, falling as she did so on a sleeping cat, who had been sufficiently aroused from its slumbers to creep by the fracas caused by the Sergeant. The cat, apparently and uncharacteristically not so intuitive as dogs and horses, was not in psychic contact with the girl’s presence, but was soon in physical contact with the invisible Debbie. One soldier, glancing over at the verandah, saw the cat rise in the air,screeching, fighting an unknown enemy — and run off around the corner, fast as a chipmunk. The soldier, forgetting one and a half centuries of Orange indoctrination of his Irish forebears, crossed himself in terror.

The girls then acted quickly to rescue their bikes and move out. In doing so they had actually to pluck at the Sergeant’s legs and leggings, and in doing that a piece of tartan cloth a foot long was torn from the Sergeant, and remained tightly wound a part of one of the cycles. Not waiting to disentangle it, the girls pushed their bikes off, even venturing to ride a short distance on Main Street where the ruts had been worn smooth. Small wonder then that the owner of the BeeHive, standing at his door, should be surprised to see a piece of coloured cloth go up the middle of the street, moving by itself in a wavy motion. He looked about. There was no wind or other obvious explanation. He then became aware of a subdued commotion across the bridge, up by the Major’s house. It was subdued because the Sergeant had now got to his feet, and between Gaelic curses was with his Celtic glare daring any man in his force to laugh at what had just happened. They, in turn, were not disposed to laugh, but were beginning to wonder if a supernatural agency were at work. By the time they came to the second bridge, the girls had to push their bikes again, and did so breathlessly.

“Lindy, couldn’t we go forward in time and get to the top of that hill without walking?”

“Be good if we could, but I don’t know how.”

They did not have to go far, however, for half way up the hill just where a rough track and a clearing showed that the concession line was there, John appeared, coming cautiously out from behind a tree.

“Little people, Sirs, what news have you?”

“Bad news, John,” said Linda catching her breath. “You must hide away, for an order has gone out for your arrest, and that Sergeant would like to kill someone

before the day is out!”

“Specially since he tripped over our bikes.”

“And you must tell Mr. Curtis and the others that their plan to assemble at noon is known, and the Major is gathering his troops to march on Norham at eleven o’clock.”

“Eleven o’clock?”

“One hour before noon. Hurry, go ahead and tell them. We shall try to be with you tomorrow.”

“Oh, Sirs, thank you. This is good news. I shall tell Master Comfort.”

“What’s good about it?”

“It is good that we know ahead the Major’s plans!”

With this, John not knowing how else to thank the Little People, knelt and acted out pouring milk into two saucers at their feet.

“John, you silly, what are you doing?”

But she did not hear his reply for at that moment John vanished, and the road became paved, with a car coming slowly over the hill from Norham.