The Topher

by Graham Cotter

Lord Durham and Reform

Illustration by Audrey Caryi

“Major, sir, there’s a strong force of men across the road at the Tavern!”

“So early? I had thought to have preceded them to that point of assembly.”

The Major and his staff were standing in the grounds of Sugar Grove. They had discovered the defeated young Cameron, and his older brother, the Sergeant, wanted to put him ‘on charge’ for desertion of duty, so fierce a disciplinarian was the Scot. The Major pointed out that every man was needed for confronting the enemy, and such matters could wait.

“The loss of a young woman radical is no great matter,” the Major had pointed out.

“We coulda held a knife to her throat, aye and cut it too, if the rebels would not surrender.”

“Sergeant you’re no gentleman!”

“No, Sorr, and a good thing, for this is war!”

“It’s not war yet, but the upholding of the Queen’s law and the order of the

realm.”

So the matter had rested. Now the scouts were back with their report.

“How many would there be?”

“Forty or fifty, about half with guns, the rest with spears and suchlike.”

The scout had noticed a single ancient pike among the back row of farmers.

“Very good. Sergeant! Lieutenant Kennedy! Lieutenant Stone! We move off in battle formation, officers at the head of the company, drummer at the rear.”

“A pity we ha’ no fife,” muttered the Sergeant, the glories of Waterloo, as he remembered them, returning to his mind.

“Men, we shall march with shouldered arms till the halt. Then trail arms and prepare to fire. No man shall fire until the word is given. I expect the sight of our force will send them home to their cows!”

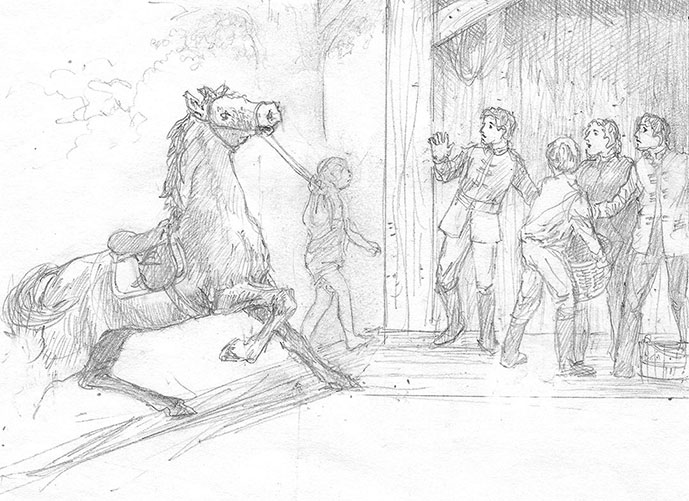

The battle formation, such as it was, was formed. The officers drew their swords, which rested lightly on their shoulders. Still only the Major was mounted on a horse, though some Tory landowners had ridden up during the march from Percy Mills and offered their services. Since they had not been sworn, the Major ordered them to form the rearguard, all three of them with one or two of their unwilling farm hands.

First, then, came the Major, his cockade a good target at least half a mile away. Then his two lieutenants, sweating in the close hot weather in their woolen uniforms – as were all the properly uniformed men – their swords held before them. Giles Stone reminded Linda of some picture she had seen of a story book monster – perhaps the one Jack had snared in his beanstalk.

Then the Sergeant, with not only his musket, but a pistol at his side, and a vicious dagger at the side of his boot. Then the men, three abreast, marching, mostly in step for once, the drummer beating his tattoo at their rear. Behind, several paces back, the late-comers mounted and walking.

Linda buzzed her sister.

“Debbie, they’re leaving Sugar Grove.”

“Lindy, we can hear them. What’ll we do?”

“Wait and see. And keep outa the way!”

“Okay. Over.”

The column swung into sight moments after leaving the grounds of the Curtis home. The rebels had a clear view up the road from the tavern, though it was thickly overhung with trees. And the beat of the drum caused many a radical heart to skip a beat of its own.

Up jumped Comfort:

“Fellow Canadians! This is our moment of glory! We stand to resist the power of Tories and privilege. And their proud arrogance is walking without caution into our trap!”

He spoke loudly, and was careful not to say ‘ambush’, for his words might just have carried to the Militia.

But the beat of the drum and the tramp of feet drowned out his words for the leading troops and officers. Major Campbell was in any case, preoccupied. He was wondering what he would do if the rebels did not disperse through fright. If they had been a troop of regulars, he would have felt better, bringing his men to a halt, having the forward ranks kneel, all ranks fire, then leading a charge with fixed bayonets. But this poor rabble, as the rebels increasingly seemed to be as they came into view, were scantily armed and were fellow countrymen.

They must commit some act of true rebellion before he could be justified in cutting them down in true campaigning fashion. The column of militia was now half way to the tavern, and Campbell could see more clearly how poorly equipped they were. He had never encountered a hay fork or a mattock, and therefore thought nothing of their possible deadly effects. But as he drew nearer, he saw the words roughly sewn upon the banner stretched across the top of the tense crowd of farmers.

“Lord Durham!” he said, and drew up his horse. He gave the signal for “Halt” with his sword. “Lord Durham! That puts another light on the matter,” he said to himself.

Wheeling around, he ordered the men to trail arms, and called his staff.

“Gentlemen! Sergeant! This is a matter for politics and not for war! Their standard appeals to the Governor-General, Lord Durham!”

“It’s a ruse, Major! They want to frighten us with his name!” Kennedy replied.

“I’ve no use for Durham,” said Stone. “I’d as soon shoot him with the rest of them.”

“Lieutenant Stone, sir, those words are treasonable.” said the shocked Campbell. “Think before you utter such things about duly appointed authority!”

Linda had crept up to hear the staff conference,

“Debbie,” she said over the radio, “They’re quarrelling over the sign that says ‘Durham’.”

“I don’t know why, said Debbie, “isn’t it a kind of wheat?”

“Silly! It’s the Governor-General. Tell John.”

Debbie, who thought the Governor-General was a brisk little man who jogged and kicked footballs on the TV, dutifully told John. John quickly spread the word.

“Aye,” said Comfort, “they’re dismayed by our banner!”

So he passed the word along the line and the shouts arose.

“Lord Durham and Reform! We stand with the Governor! God save the Queen!”

The Norham farmers were more sure of their Sovereign’s sex, and her newness at the job, than the Tories of Percy Mills! The cries went on, and the tension broke among the farmers. They tossed their hats in the air.

“Hurrah for Radical Jack!”

The men in front, bearing the firearms, did not follow suit. Each man had picked a target. So also had the ambush parties on each side of the road, or at least those with guns. But those others in ambush, whose hands were free, broke silence, and whooped with the rest.

Andrew Boyce, one of the mounted men who had come late to the militia, rose up quickly to the Major.

“Major Campbell! There are men in ambush, down both sides of the road! There are even men behind us, aiming guns.”

“Thank you Mr. Boyce.”

“Major, Sorr,” said the Sergeant, “We must attack now, while they’re excited and not attentive.”

“Attack! “Attack!” came from the fully uniformed ranks.