The Topher

by Graham Cotter

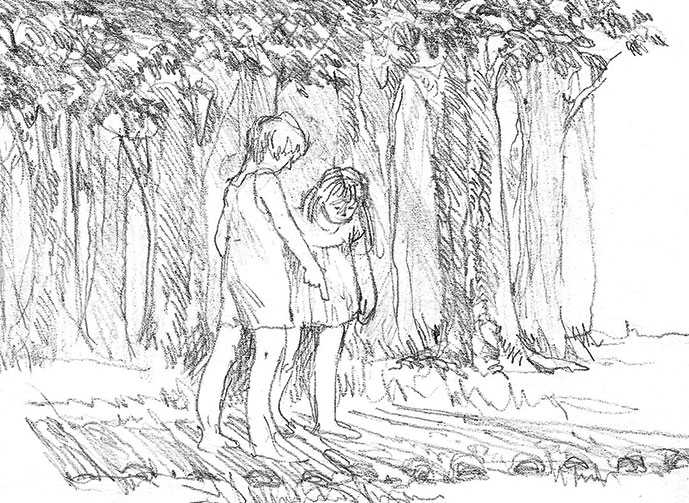

Corduroy

Illustration by Audrey Caryi

The road they took was gravel, and led north for about a mile, then was forced to turn east. From here on it would run roughly parallel to the river and meet the river in the village of Warkworth. But in the mean-time there were many ups and downs.

While the downs could be taken at speed, during the ups the girls had ample time for looking about them as they walked the machines. As well as the winding patch of the river to the south, they could now see a wide marshy expanse to the north. Though only local people would know it was marsh for at this time of year the hardwood which grew there was in full leaf.

“Lookit all the green tops of trees, Lindy!” said Debbie.

“Lotsa them!” puffed Linda, stouter than her sister. “They’re so pretty! Who owns them?”

“I don’t know who owns them, silly. They stretch up to the farms on the road to Roseneath.”

“Where the horses are? I love the horses.”

“But the trees are in wet ground that goes towards Dartford Pond.”

It was very important to Linda to know more than Debbie, it made up for being plump, freckle-faced, and intelligent, whereas Debbie, Linda felt, had the real superior advantage of being pretty.

They pressed on. At one point they passed a lovely stone house with a neat lawn and even a little bridge crossing a tiny trickle of water. By contrast, over the next hill there was a dilapidated frame house, leaning at an angle next to the remains of a little lake, with the debris of farming and automobiles piled along the road.

“Litterbugs!” sneered Linda as they rode past.

“Litterbugs, jitterbugs, flutterbugs, butterflugs, butterflies!” echoed Debbie.

“See, my magic made them nice after all.”

It may not have been Debbie’s magic, but the next house they came to had been loved by some former owner. It nestled just shy of the top of the hill, out of the path of the prevailing wind. A neat garden had been made, with rose arbors and fences, and even a broken-down summerhouse at the end of the lawn spoke of another time when someone had tried to create beauty in the midst of hard farm life.

“Slow down, Debbie, here’s our turn coming up.”

They turned on to an even rougher road, which would take them across the stream. The road narrowed, entered the cedar woods, and then there was a little bridge. The stream seemed smaller than at Burnley, but maybe it was deeper and narrower.

“Couldn’t we have crossed lower down, Linda?”

“At Bantytown, by the Lumber Company, then it would be harder to ride home.”

“I thought there was somewhere else.”

“There is,” said Linda, stopping in the middle of the bridge and walking her bike, glad of the chance to catch her breath.

“But Mommy doesn’t want us to go that way.”

“Why not?”

Debbie knew there was another road about which there was some mystery, and wanted to draw her sister out.

“Because of the Hippies’ Pond.”

“Hippies’ Pond?” queried Debbie innocently.

“Yes,” said Linda righteously. “One of the men who drives for the township said the hippies tried to keep him from using the bridge. He said there were hairy men and women running around and swimming with no clothes on!”

“No clothes on!” Debbie liked the idea, but didn’t want to say so. “They must look silly!”

Linda said nothing and walked on. She wasn’t sure whether she liked or hated the idea of Hippies’ Pond, or what attitude she was to take while her sister Debbie, cheerful as ever, mounted and rode on, singing as she went.

“Hairy things, swimming in the river, hairy things, bobbing up and down!”

They were now coming out of the cedars, and after a few hundred yards would again reach the concession road which led home. It was a familiar place, for they had often come this far from their house, and they looked again at the great bare hill, the drumlin, with its fences of stone and its barn nestled at the foot.

They were each riding along, with Debbie in front, when from nowhere, it seemed that a cloud had covered the hot bright sky. At the same time the road became much rougher underfoot, and they could not go on pedalling.

“Debbie, stop! Something’s queer about the road!”

“Yeah, look, logs!”

Where the gravel road gave out the way was paved with logs. They had sometimes seen a log come up from under gravel or tar in the spring washout, and Linda remembered something from school.

“It’s like Miss Chambers told us about the old roads. They were made of logs to keep down the mud. Corduroy, she said.”

“Corduroy! That’s for making pants!”

“No, it’s really a road and it means the King’s Wood.”

“King’s Wood? Well, it’s not much of a road.”

The girls were so intent on what had happened to the surface of the road that they did not notice the change which seemed to be a great cloud. There was no great cloud, the day continued as hot and bright as before, but the woods were still around them, tall pines and hardwood trees. They were in deep shadow.

“We should be out the woods now, Lindy!” We should be and we’re not. It just doesn’t seem the same road.”

“But there’s the crossroad ahead, Lindy. That must be the way home.”

“Yes, but there was a field here, and we could stand at the crossroad and look at the big hill with all the fields on it, and the stone fences.”

By now they had walked their bikes to the crossroads. It was in the right place, but did not look familiar. In the direction of the hill, however, there was a bit of a clearing, and they both turned to look for familiar landmarks.

“There’s the hill!”

“But it’s different, Lindy, too many trees.”

“Look Debbie, there’s the long stone fence at the edge of that field.”

There was a filed cutting like a sawtooth into the hill, with stone walls at each end. In the middle of the field were the distant figures of a horse and a man. He seemed to be pulling at a stone in the middle of the field. But what took most of their attention was that the drumlin, instead of being bald as they knew it, with several such fields and the occasional tree line, was, except for this one field, covered in thick forest, as far as they could see above the tops of the trees at the edge of the clearing where they were standing. Before they could react to this second strange situation of the day, there was a sound of horses’ hooves behind them. Along the road, from the direction towards home, came a man riding at a good trot, the hoof beats rich on the logs of the corduroy road. It was a big horse, not a pony as might be expected, and there was a big man in a black coat riding it. He must be boiling, they thought, in that coat on a day like this. They noticed he was in black breeches, and that he had a strange white fluffy thing at his neck. His hat was a bit like the Calgary stampede hats sometimes seen on men driving bright new pickup trucks, but it was also black and worn and faded.

The horse, they soon noticed, was a mare, and as she drew near, she began to whinny and shy and dance, starting away from where the girls stood. The rider held her with some difficulty and then stopped, just a few feet away from them.

“Cherie!” he said in a deep voice. “What frightened ye, lass?”

He looked sternly, right at the girls, as the mare stamped and snorted. He clearly did not see them, though he seemed to look Linda right in the eye.

“There’s nowt, nowt at all. Now gie on, or we’ll be late for the good people.”

In response to his spur, the horse, prancing and whinnying once more, suddenly bolted along the road.

Debbie burst into tears. “Lindy, I’m frightened. We’re lost. I don’t know where we are!”

She wailed loudly and hugged her sister.

“You’re all right Debbie, and so’m I.”

But Linda held on to Debbie hard as the younger girl grabbed her. She was terrified, and her quick mind, not clouded by the energy of crying, told her that she had just seen — perhaps — a ghost. But she didn’t believe in ghosts.

“We’re lost!” screamed Debbie, now beginning to shake Linda in panic.

“We’re not lost. We’re in the right place, and we have our bikes — and the walkie-talkie too.”

With that Linda pressed the button on the little radio. No answer. So she pressed another button. The electronic shop in Cobourg had arranged for a special alarm receiver at the Scace home which would sent out a beep like the pocket bellboys used by doctors.

Both girls waited. It would take their Mummy a few moments to get to the transmitter. As they waited they looked along the road where the rider had disappeared. The house was there, the same one they knew, but it was very different looking. Instead of red brick siding, it was made of logs, and the logs still looked fairly new. There were no lilac bushes growing in front of it, and there were cows grazing at the front door.

“Girls!” came their Mother’s voice, “Did you call, are you all right?’

Debbie started to wail, but Linda pinched her.

“We’re okay, Mum, we just want to know what time it is.”

“It’s about three o’clock. Where are you?”

“We’re by Drumlin Hill, just turning to come home.”

“Okay. See you soon. Nancy and out.”

“Look Linda, look!” Debbie was shocked out of her whining.

“What?”

“There the hydro pole! It wasn’t there a minute ago. I just saw it

appear right where I was looking.”

“Wow! Now the road’s changed back to gravel, too.”

Both girls with a single thought turned back towards Drumlin Hill. The whole scene had changed. There were now open fields all the way to the hill, and the hill itself was bare, but for those stone walls and tree lines. At the end of the road, the house was there, but in the form they were accustomed to, not as they had seen it just a moment ago.

Without a further word, both girls leaped on their bicycles, and started off along the road home. There was a slight rise, but you would not have thought it made any difference. They both rode as though there were a hurricane chasing them and were soon over the top of the rise, leaving the countryside hot and peaceful behind them.