The Topher

by Graham Cotter

Some Dreams Retold

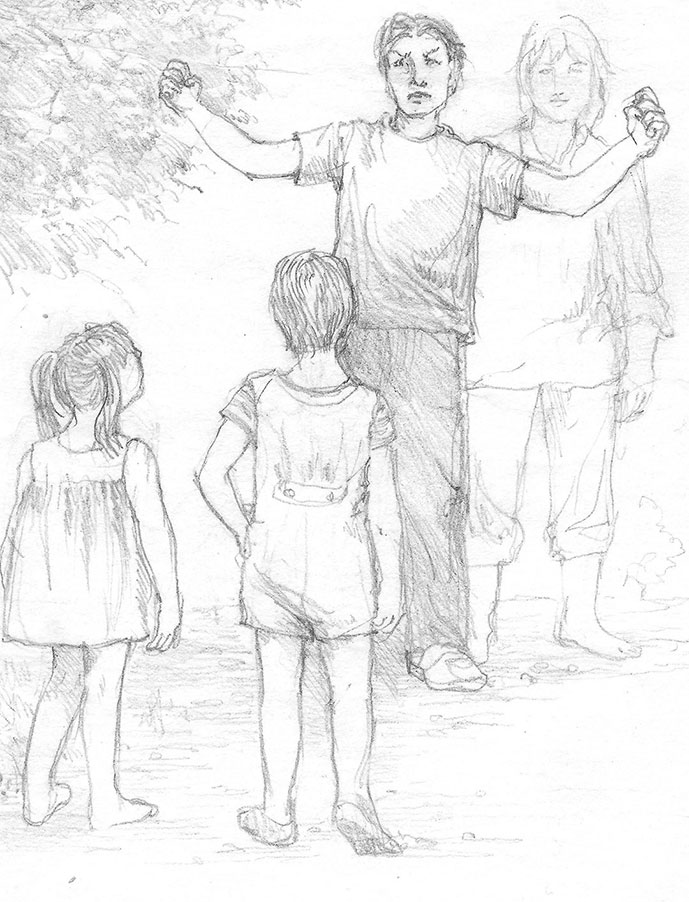

Illustration by Audrey Caryi

He stepped forward, all intent, far less cautious than they had seen him before.

“Did you get to see Martha?” he asked.

“Martha?” said Linda stupidly.

Debbie rushed over to the Topher and caught him. No longer terrified, she was entering into the game, as though she had been allowed to step into a TV story. She looked up in excitement, her long fair hair getting in her eyes, and said,

“Were you John, just now?”

The Topher pulled himself together, and began to laugh nervously.

“Let’s sit down somewhere,” he said.

“Hey,” said Linda, “you musta been John, or how could you know about Martha?”

She advanced aggressively, trying to apply common sense to the unexplained and perhaps to unexplainable events. The Topher, meanwhile, led Debbie, Linda following, to a big log, one of the old trees now fallen. Debbie began to babble.

“It was a big house just here,” she swung her arms around, “and there was an old man with a beard, a whole lot of men around the table, and this John.”

She cocked her head to one side.

“You musta been John.”

“Now just a moment,” said their friend, “Were you both there, at this house I mean?”

“Yes,” said Linda. “And there was a man at the door who called John inside?”

“Yes”

“And this John was in love with Martha?”

“Yes, but we didn’t see Martha, we just heard her.” said Linda.

“And what happened in the room?”

“There was a thin man at the table called Comfort and he talked and talked to this John about something — something to do with government and all that.”

“And when did you come back to now?”

Debbie spoke up again,

“We were just following John out to see Martha — and we missed her!”

“So,” said Linda, standing full in front of the Topher, “If you’re not John,

how do you know all this?”

For the first time the Topher lost his temper with her,

“Don’t you see, it’s complicated, I’m not John, but I know what goes on in his

head!”

With this he jumped up, bowling over poor Debbie who had been hanging on to his arm. He stood over them, tall and furious.

“It’s very, very, complicated and it’s very, very hard! I’ve known John all my life. I know where he lives, and what he eats and what he thinks. But I’m not John!”

He stamped his foot, his fists held out, and his blue eyes glaring at them.

“Okay, said Linda, “We believe you.”

Normally she would have been scared of a six-foot young man shouting at her here, away from people. But she felt she knew this one very well. Besides, it gave her a sense of power to be cool when he was out of sorts.

“Why don’t you tell us about it?”

“Right,” he said, collecting himself once more.

He was a little embarrassed, being ordered about by a young girl. But then she and her sister had really been in that world he had only seen in dreams and imagination. There must some reason for his having discovered them, or their having discovered him. This was a special bond between them too, this common knowledge of uncommon events.

“I first remember,” he said when they were comfortably settled again, “when I was a little boy in bed. I think I was sick, anyway, I was looking at the counterpane.”

“What’s a counterpane?” asked Debbie.

“Bedcover, and shhh.” said her sister.

“It was like a quilt with lots of different pieces of cloth, different colours, and sewn to make patterns. There was a big bump where my body was, and another big bump where my teddy bear was, like two hills. I guess I was going off to sleep, or waking up, because all of a sudden, I was small, and the hills were real, and I was walking along the top of one hill. A big man was holding my hand and said, ‘That’s Norham, down there John boy, and that’s where we’re going to live.’

“I don’t remember seeing Norham that time, just seeing green trees, and I remember the big clouds that were coming up in the sky. I suppose it must have been an east wind, if I was standing on your hill and looking to Norham, and east wind means wet weather or snow. Anyway, I was scared.”

“That’s the first thing I remember, try as I can. I can’t go back before that. Since then I would have dreams, and in the dreams there was a special country all my own. It was called Norham. There was a log cabin, among the trees, and a field where John’s Dad would push the plough while the big horse hauled it, and as I grew older I learnt to push the plough myself — or John did. I never seemed to see John, I seemed to be him. But it was dreams, you know. Dreams in sequence, so that after a while I knew all about his life, I observed it, and we seemed to grow up together. But he didn’t know about me, not the ‘me’ in whose dreams he existed. Do you understand?”

“No,” said Debbie.

“A little,” said Linda.

“Tell us about Martha.” said Debbie.

“Martha was beautiful. First saw her — John first saw her — when he was little, driving past Curtis’ place just now — say, right here! This is the very place!”

He stopped in amazement, as he realized that they were sitting at the very place John had come to court Martha. Again he jumped up, and went looking around for reminders of what he had known in his dreams. Then he sat down again, and put his head in his hands.

“Lord! It just hit me! They’re all dead and gone now, dead and gone for a hundred years!”

His eyes were moist. Debbie was upset.

“No, Topher,” she said, “They’re not dead. We just saw them. We just heard

them walking. John winked at us.”

He looked at her doubtfully, and then realization dawned on his face.

“That’s right,” he said, smiling through his tears, “though it doesn’t make any sense. But I saw what happened too, through John!”

“So,” said Linda, “you were telling us about Martha.”

“Yes. She was very small when I first saw her. I was small too, I — John, was going to the grist mill with John’s Dad at Percy Mills. And Martha was playing there, in this very yard, wearing a little long dress like a doll’s and a bonnet, and her face was red, she was like a wild raspberry rose, with black hair coming out underneath the bonnet. John fell in love with her from that day, and I did too.”

“Then you were John after all.”

“No. But in my dreams about John I saw everything the way he saw it, and felt everything the way he felt it, and only when I woke up I remembered that I was different from John. But his feelings spilled over into my own life, so that when I was at school in Toronto I would look around the classroom for John’s Martha, and never find her.

“So John grew up loving Martha. After a year or so he got brave enough to talk to her. If they met in the town they would approach each other shyly and find something to say. Occasionally, very occasionally, there would be a visit between their two families, or their fathers would be at a house-raising or barn-raising together, and as John and

Martha grew older they would work together at some small jobs they were given.”

“What’s a barn-raising?”

“When all the neighbours would get together and raise up a barn, or a house, in a day. The man whose barn it was would have the wood ready and cut, but he needed the combined efforts of everyone he could find from round about to raise it up. It was a bit like a modern prefab, where the parts of a house are made in a factory, and a crew of men put the pieces together all at once.”

“What would the children be doing at a thing like that?”

“Well, the women would be cooking meals and serving beer or whiskey to the hardworking men, and the children would help.”

“Were you always with John,” asked Linda, “how did you get time to grow up yourself?”

“No, I wasn’t always there. I was there in my dreams, and I grew up and went to school like anyone else. But I always had this life with John at the back of my mind, as I said, the dreams were in sequence.”

“What does that mean?”

“In the right order. But they weren’t really. I would often go back in my dreams to a time younger than John was and younger than I was, and find out some things I hadn’t ever before.”

“Could you go back if you wanted to?”

“No, it would always just happen. And I never went forward, I never dreamt anything about John which would have happened when he was older than I was.”

“Are you sure it was Norham?”

“Quite sure. It was called Norham. It looked different. There were lots more trees, and the roads were muddy paths in winter, and grown over with weeds in summer.”

“Did you know when it was — what year it was?”

“Most of the time, no. Sometimes John would hear somebody talking about what year it was. John didn’t go to school too much. His mother taught him to read and write a bit, and to cipher, as they called math. But he was working hard around the farm from very young.”

“Were you ever scared by your dreams about John?”

“I was scared with him lots of times. Like when he was chased by a bear, and when he was beaten up by a boy in Percy Mills. But the times when my dreams turned into nightmares were when I knew something better than John and couldn’t do it because John could not hear me or know what was on my mind.”

“How d’you mean?”

“When John was trying to read something, and I could see the words through his eyes, and yet I couldn’t read them because he couldn’t read very well – I’d wake up raging with frustration, and of course, I would never know what was written down.”

“Do you still have these dreams?”

“No, except for what happened just now.”

Linda thought for a moment, trying to put together the various things which had happened to them in the past half hour. Then she looked up, questioning all over her face:

“How could you have had a dream just now when you weren’t asleep?”

“It was just like being asleep. Let me tell you. Debbie said something about us being so far away from the rest of the world, and you, Linda, tripped. Then it was just like a camera shutter, or one of these funny changes of pictures they have on TV. You and Debbie were still where you had been and John was where I had been. I was seeing from inside John.”

“But were you – really?”

“I must have been inside John.”

“But if Mummy or Daddy had come into these trees just then would they have seen you?”

“I don’t know. For that matter, would they have seen you two?”

“If we were really back there at Curtis’ house, then they couldn’t have seen us, here, back in the now.”

“But Lindy, Topher was dreaming with his head. His body might have been right here!”

“Well it might have been — !”

“What?”

“When you came back — I mean, when the Curtis’ house and John disappeared, I was several feet away from you. Remember?”

“Yes, Tophy, you were over here.”

Debbie ran over to one side, about where the lawn of the Curtis’ house had been.

“So I think… that my body stayed here — over there — while my mind went with John into the house. And then when John went into the summer kitchen, I didn’t go with him.”

“And we came back to now!” said LInda.

She thought quietly for another moment, and then said,

“Hey, how come John could see us and knew us? He musta seen us before.”

“You’re right,” said the Topher, getting excited. “John had seen you before, I know it.”

He stamped the clearing, puzzled.

“But, when did you see us first through John?”

“I don’t know. You see, I haven’t dreamt of John for a long time. Almost a year. But I’ve thought about him, and Martha, a lot. In fact, that’s really why I came up here for my holiday. To be by myself, and maybe dream of John again.”

“Aren’t you by yourself in the city?”

“No, I — ”

At that moment the buzzer of the walkie-talkie went.

“Just a moment Topher.” said Linda.

She ran over to where the bicycles were parked.

“Hello Mum.”

“Are you both all right? Linda?”

“Yes.”

“The Topher still with you?”

“Yes.”

“Where are you?”

“The Curtis’ place.”

“Curtises?”

“Oh, you know Mum, where the Curtis’ house used to be. Between Norham and Warkworth among the maple trees.”

“I see. Didn’t know you knew it was Curtis’s. That house has been gone

since before you were born, Linda.”

“Yes Mum.”

“You should be starting back pretty soon. And I want you to pick up some yeast at the BeeHive.”

“But Mummy, I don’t have any money with me!” Linda was exasperated at this intrusion from the ordinary things into their adventure.

“It’s okay. Tell your Mum I have some with me.” said the Topher.

“The Topher says he’ll pay for it. Bye, bye, Mum.”

“Nancy and Out.”

“Nancy and Out.”

“Whew, she’s always checking up on us.”

“Well she must think it a little strange. Living by myself in the woods and taking her little girls off on a bicycle ride.”

“No, there’s nothing strange about it. I think she likes you.”

“Oh, Topher,” said Linda hastily. “you were saying you’re not alone in the city. Do you still live with your mother and father?”

“No, I live with my girlfriend, Mary.”

“See, I thought you did.”

“You’re married?” asked Linda, as though marriage was a disease.

“No, we’re not married. But people often live together now when they love each other and before they get married.”

“I see.”

Linda was silent. She had heard about that, too, but having heard about it didn’t make it any easier to understand.

“Well, we’d better get going. Your Mum wants you home, and you have to pick up some things.”

“Just yeast. Okay, we can go this way.”

They pushed their bikes back on the gravel road, and Linda guided the other two north, rather than go back by the way they came. To their right was a modern house, a bit back from the road, and the gravelled road itself turned left and went through the yard of the township roads department. They it joined the main road to Warkworth, just at the top of the hill.

Before them and below them lay Warkworth village. Northumberland County in Ontario had more villages than any other Ontario county, and this village, declared to be the Hub of the county by the local Journal, is the prize of them all in picturesque beauty. Some wise person about forty years ago planted out in evergreens the hill that rises behind the village. Beneath this hill runs the Mill stream, the Conservation pond, and the county road to Highway 30. As the three youngsters approached from Norham they could see this, and the line of the main street lying ahead of them, the spire of St. Jerome’s to the right, and pastures still creeping up to the business centre of the

village.

“It’s Percy Mills, though it looks different. See, the Mill would be just over there.”

He pointed towards what is now the Co-Op building, by the pond.

“No, that’s Warkworth, silly.” said Debbie.

“I’m sure it’s Percy Mills.”

“Is that where that man said it cost too much to grind the grain?”

“Yes, Debbie, that’s it.”

“I’ve never heard it called anything but Warkworth,” said LInda, “But it is the township of Percy.”

“Well, we’ll see,”

They then pedalled down into the main street, passing the plumber, two gas stations, the Municipal building and the United Church, and on into the stores. At the very end of the BeeHive, whose roof, though old, was like the Second World War Nissen huts which were all over British North America. Here Topher bought yeast for Mrs. Scace, and ice cream cones for the two girls, which they ate as they pushed their bikes past the pond and towards Cemetery Hill. They began to talk again as the cones dwindled away.

“Topher”

“Yes, Linda.”

“You said, back there, that you needed to be by yourself so you could dream of John again….”

“Yes, that’s how I felt when I came up here.”

“How long since you dreamed of him?”

“Oh, about a year.”

“Have you and Mary been living together that long?”

“About that long, yes.”

“Do you think there’s a connection?”

“Maybe. Anyway, when I fell in love with Mary I just didn’t dream of John anymore.”

“Gee, ‘magine being in love; that would be lovely for me,” said Debbie.

“It is lovely. It was nothing to do with Mary; it was something to do with myself.”

“If you were my boyfriend,” said Debbie, “I wouldn’t want you to be thinking of anyone else, especially in silly old dreams.”

Topher’s reply came back harshly.

“And that’s why you couldn’t ever be my girlfriend when you had ideas like that.”

“Oh-oh, you nasty boy!” Debbie was furious, and rode off ahead of the other two, but not so far ahead that she could not hear what they were saying.

“What did you think was missing?”

“Well, I’d lived with John inside me all this time, and I felt as though I had deserted an old friend. I felt he might need me, and I was just looking after myself. I couldn’t dream of him anymore, so I found there really was a place called Norham. I decided to come here and see for myself.”

“And was today the first you had seen of him?”

“Yes, but I thought about him all the time. Even when I was doing my yoga — you know, standing on my head and all that, trying to make my mind empty. It was to make it empty so that perhaps he would come into it.”

“And he didn’t.”

“No, though I would think about him and go over all the experiences I had with him. But nothing new happened.”

“Did anything else happen?”

“I made up some songs. Maybe I’ll sing them to you sometime.”

“Oh, sing us one now!”

Debbie was back at his side, beseeching.

“You expect me to go up this long hill and sing a song too!”

“Well, wait ’til we get to the top.”

So when they reached the top of the hill, just where the ditches turn and run in opposite directions, they stopped and the Topher caught his breath.

“You know,” he said, “about drumlins?”

“There’s Drumlin HIll, where we saw the rider and his horse.”

“Yes, and this is a drumlin we have just come up. Drumlins are all over this part of Ontario, and they all point in the same direction — the direction the glaciers, those great mountains of ice, retreated in years ago. The direction of the drumlin is called its axis, plural axes.”

“Sounds like a geography lesson.”

“No, it’s a song and it’s about the direction of the hills and the directions of my life. Here it is.”

He began to sing, unaccompanied, in a low hoarse voice, not really singing but chanting:

The drumlins lie with long low slopes

their axes all northeast;

and soil, like webbing, links their feet

and rocks bestrew their brows.

Hill after hill, with various shapes,

and streams that cut apart;

forests drown some, and others, fields,

where men have worked their lives.

The Drumlin land between the lakes,

from Ontario to Rice, and on its edge

Kawartha’s fingers point

where glacial mountains moved their mass

engraved our treasured land,

uncovered blessings for us, unborn,

by mindless purpose driven.

My axes, like the drumlin hills,

but not all pointing there,

they cross, and mix, and leave me dry;

my woods of flesh crown some few heights,

while others gleam with work,

and in between some rivers flow,

and roads and mills and grist.

Sometimes, with luck, by love or labour,

my mobile mounds all turn

and face one way

and then my day

is bright,

my night

moon steeped and star bespecked –

He stopped. The girls gaped at him, loving the chant, not quite knowing the words.

He said, “I don’t think it’s finished, but I don’t know what it needs.”